New tool for general neurologists aims to streamline differential diagnosis

Researchers from Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health have contributed to development of a new diagnostic algorithm for general neurologists that can help them distinguish among atypical parkinsonian disorders (APDs).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The practical and easy-to-use tool is described in a consensus statement from the CurePSP Center of Care (CoC) Network that was published in Neurology Clinical Practice. (2024;14:e200345).

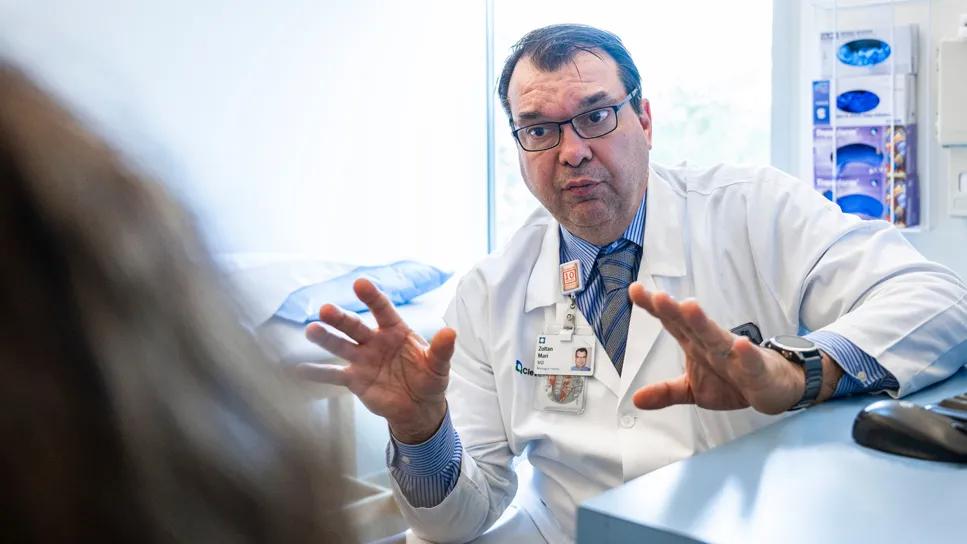

“The over-arching flow diagram and tables our working group created address 64 APDs, but there are many more,” says neurologist Zoltan Mari, MD, director of the CurePSP CoC at the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Nevada. “The focus of the tools is on progressive supranuclear palsy and Lewy body dementia, because they’re the two most common APDs, easiest to diagnose and we don’t want clinicians to miss them.”

Cleveland Clinic Nevada is a Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence and one of only 32 centers in the United States to have earned the designation from CurePSP. The nonprofit organization is dedicated to state-of-the-art care for progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and multiple system atrophy (MSA).

Backdrop to the algorithm

The need for the algorithm was underscored by an online community survey that CurePSP conducted in 2022. The respondents – 234 patients and care partners with APDs – said they believed the two most important barriers to high-quality care were clinician lack of familiarity with the disorders and delays in diagnosis.

“Many patients with APDs have symptoms for years before their specific disorder is identified,” says Dr. Mari, “and these conditions progress rapidly, so getting an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment early is crucial to better outcomes.”

Advertisement

APD identification is challenging because the conditions share some of the signs and symptoms of parkinsonism, but they have a variety of other atypical features. The origins of APDs may lie in neurodegenerative diseases or be structural, genetic, vascular, toxic/metabolic, infectious or autoimmune in nature.

In addition, there are no diagnostic criteria for some APDs, subspecialty experience often is needed to implement the criteria that do exist, and competing diagnoses must be ruled out with little guidance about how to do that.

Algorithm key features

The new algorithm is based on criteria commonly employed in research studies of APDs and used in practice at the Lou Ruvo Center. It emphasizes the iterative nature of diagnosis. At any point in using the tool, the work group encourages general neurologists to make referrals to a tertiary center if they believe that would be in a patient’s best interests.

The flowchart starts with a detailed history, detailed neurologic exam and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast. The clinician compares the resulting data with tables of diagnostic clues to the seven major APDs and of related brain MRI findings.

“If you see the hummingbird sign on a patient’s MRI and they have an eye movement abnormality such as inability to look down, the diagnosis is PSP,” says Dr. Mari. “If there is no visible brain damage, it’s time to look at the diagnostic clues and consider whether the individual has a rarer APD.”

Biomarker testing and non-MRI imaging also can be obtained to assist in diagnosis, but the authors emphasize that it should only be done by clinicians familiar with the implications of the results for APDs and the limitations of the findings.

Advertisement

Says Dr. Mari, “Assays for alpha-synuclein are now commercially available and they’re usually negative in patients with PSP and positive in patients with MSA.” He notes, however, that “for APDs, a good history and neurologic examination, along with the tincture of time, are the best diagnostic tests. The work group also strongly advises that clinicians discuss diagnostic tests with patients and their families to ensure that the information to be gained aligns with their clinical goals.”

The next steps for the work group are to investigate whether the algorithm can be improved with artificial intelligence and to develop a version specifically for use by specialists.

“We may be able to employ machine learning, for example, to analyze the data we’ve already accumulated on biomarkers and facilitate diagnosis,” says Dr. Mari. “We’ll also be validating, revising and updating the current algorithm based on new findings as time goes by.”

Cleveland Clinic’s Neuro Pathways podcast recently interviewed Junaid Siddiqui, MD, on this topic. Dr. Siddiqui, a movement disorders specialist in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Neuro-Restoration, is an author on the consensus statement. Click here to listen to the podcast.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Various AR approaches affect symptom frequency and duration differently

Dopamine agonist performs in patients with early stage and advanced disease

Early assessment could affect clinical decision making

Systems genetics approach sets stage for lab testing of simvastatin and other candidate drugs

Study aims to inform an enhanced approach to exercise as medicine

When and how a multidisciplinary palliative care clinic can fill unmet needs for this population

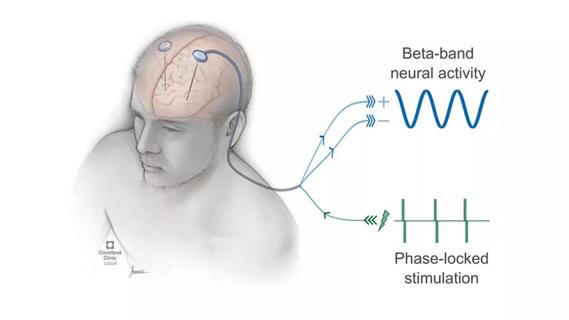

Research project will leverage insights into neural circuits to advance DBS technology

Randomized trial demonstrates noninferiority to therapist-led training