Treatment differs from other types of uveitis

Syphilis, once thought to be nearly eradicated in the U.S., is making a comeback. Incidence of the sexually transmitted infection has risen nearly every year since 2001, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. From 2017 to 2018, the number of cases of primary and secondary syphilis reported in the U.S. increased 14.4% (from 30,644 to 35,063).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Ophthalmologists can play a major role in caring for patients with the disease, which can manifest as uveitis. But syphilitic uveitis can be challenging to diagnose because the inflammation can present in various ways, says Arthi Venkat, MD, an ophthalmologist at Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute.

“It’s important to test nearly every uveitis patient for syphilis,” she says. “If you don’t diagnose and treat syphilitic uveitis properly, patient outcomes can be devastating.”

In this case study, Dr. Venkat explains what to watch for and why ocular syphilis should not be treated like other types of uveitis.

A middle-aged man reported decreased vision in both eyes over two weeks. Visual acuity was 20/250 OD and 20/80 OS. He had not seen a physician in more than 10 years and reported constitutional symptoms of night sweats and weight loss.

“This patient said he was sexually active with multiple male partners and did not use protection,” says Dr. Venkat. “Anyone who engages in unprotected sex with multiple partners, regardless of sexual orientation, is at risk.”

Fundus photography showed areas lateral to the fovea with a notably stippled appearance.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/279c3b40-1e55-4d5f-8d71-3ea63ceb83ae/20-EYE-1875120-CQD-Syphilis-Case-Study-Inset-1-300x109_jpg)

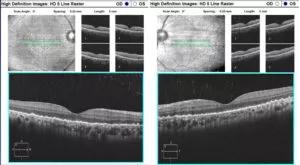

On optical coherence tomography (OCT), the retinal pigment epithelium appeared irregular and nodular — a sign frequently associated with syphilis, especially in immunocompromised patients, notes Dr. Venkat.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f33e47ff-278c-4e12-8f6a-5b931a7a0af7/20-EYE-1875120-CQD-Syphilis-Case-Study-Inset-2-300x165_jpg)

“Syphilis in patients with stronger immune systems may manifest with more visible inflammation on exam, in contrast to this patient, whose inflammation on exam was subtle,” she says.

Advertisement

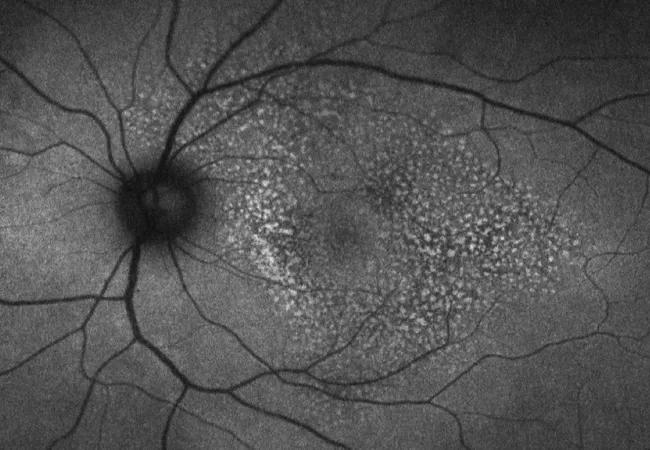

Imaging studies revealed more inflammatory activity. Dr. Venkat noted multifocal areas of hyperautofluorescence on fundus autofluorescence, indicative of outer retinal inflammation.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3e588a78-3013-4a42-9731-7a3a207275bd/20-EYE-1875120-CQD-Syphilis-Case-Study-Inset-3-300x168_jpg)

“Based on these findings, syphilis is very high on the differential,” says Dr. Venkat. “The other less likely conditions that can look like this are sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease and primary vitreoretinal lymphoma.”

Results of syphilis IgG testing were >8.0, indicating that the patient was previously infected with syphilis. A rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test result of 1:128 indicated that the patient was actively infected.

Because compromised immunity was suspected, the patient also was tested for HIV and was found to be positive.

The patient was admitted for intravenous (IV) penicillin and further evaluation by infectious disease specialists.

“Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines categorize ocular syphilis as neurosyphilis,” says Dr. Venkat. “That’s an important distinction. Neurosyphilis requires either IV penicillin or a combination of intramuscular penicillin with probenecid. One cannot treat ocular syphilis like primary syphilis, with oral antibiotics alone.”

Brain MRI, cerebrospinal fluid cytology and abdominal CT ruled out lymphoma. Testing for other diseases on the differential also returned negative. Cerebrospinal fluid RPR was reactive (1:256), confirming neurosyphilis.

On Day 2 after IV penicillin, the patient was started on steroids to temper the inflammation that can occur as syphilis responds to antibiotic treatment.

Advertisement

“Steroid treatment for uveitis is common, but in syphilitic uveitis, steroids without antibiotics can cause irreversible vision loss and other devastating systemic effects,” says Dr. Venkat. “Antibiotics must be on board when giving steroids to someone with ocular syphilis.”

With treatment, the patient’s vision improved significantly. Some patients with ocular syphilis may not have complete recovery of vision depending on the extent of retinal involvement.

Ocular syphilis can be the primary presentation of an otherwise asymptomatic infection. That’s why Dr. Venkat includes syphilis testing as protocol for all of her uveitis patients.

“Syphilis is one of the most common infectious causes of uveitis that I see,” says Dr. Venkat. “In this case, the patient likely had syphilis for a long time, but was unaware of it until progressing HIV reduced his immunity to a point that caused symptoms to appear. That’s a common scenario.”

Uveitis, in general, can be chronic and difficult to treat, often requiring ongoing steroid treatment or immunosuppression. In contrast, syphilitic uveitis is relatively easy to cure with antibiotics. Steroids can be used along with penicillin to treat inflammation. Proper testing and diagnosis allow for timely management of this highly treatable form of uveitis.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

Treatment options range from tetracycline injections to fat repositioning and cheek lift