If denosumab is stopped, it should be replaced with another osteoporosis treatment

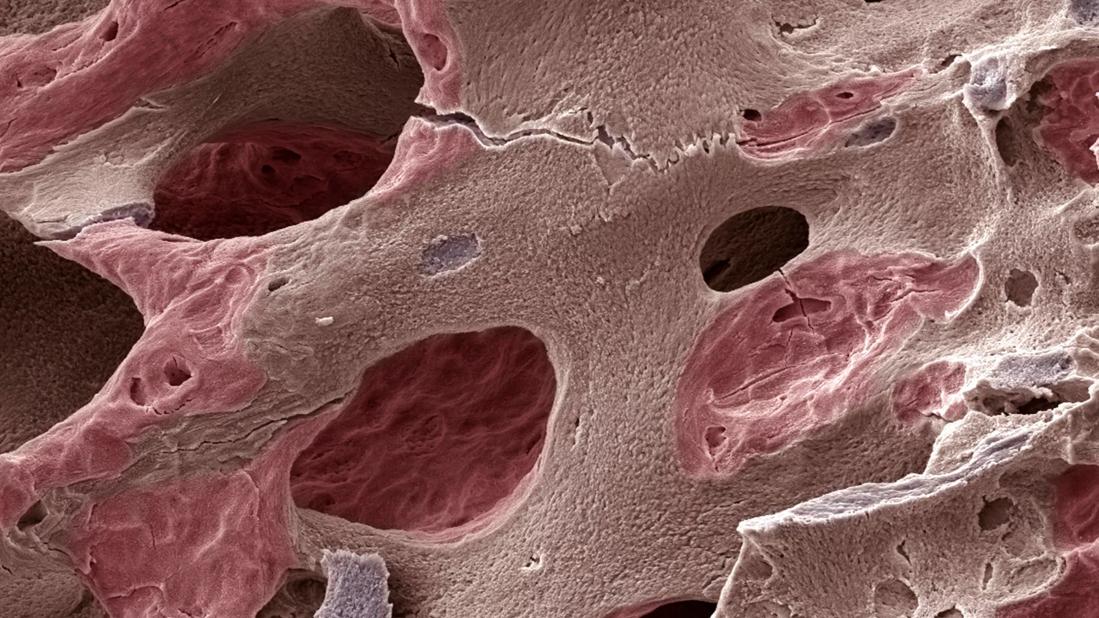

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2c5210de-caf4-4cf7-8494-c0c96364b451/17-RHE-1177-Deal_ConsultQD_Hero-Image_650x450pxl_jpg)

17-RHE-1177 Deal_ConsultQD_Hero Image_650x450pxl

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. For the full article, please click here.

Physicians and patients have become accustomed to a drug holiday with osteoporosis therapy. The American Society for Bone and Mineral Research has published recommendations for long-term bisphosphonate treatment,1 in which they suggested that after five years of oral or three years of intravenous bisphosphonate treatment, one should consider reassessing fracture risk.

In women who have no factors that place them at high risk for fracture (hip T score less than −2.5, FRAX score indicating high fracture risk, previous fracture, or fracture on therapy), a holiday should be considered. For patients at high risk, continuing for up to 10 years of oral and six years of intravenous bisphosphonate should be considered.

But a holiday is not forever. Therapy often needs to be restarted, especially if bone density declines or a fracture occurs.

A holiday is suggested since long-term use of bisphosphonates has been associated with atypical femoral fractures, and higher doses and longer duration of use have been associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw.

However, in the case of bisphosphonates, a holiday is “administrative.” Although administration of the drug is stopped, these drugs have a long half-life in bone, and their pharmacologic effects continue for years after discontinuation, depending on the drug and duration of treatment.2 This prolonged effect after discontinuation is not the case with other therapies for osteoporosis, including the parathyroid hormone analogues abaloparatide and teriparatide, estrogens, estrogen agonists-antagonists (e.g., raloxifene), romosozumab and denosumab.

Advertisement

Romosozumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against sclerostin, a cytokine in the Wnt signaling pathway that inhibits bone formation, and denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody against RANK-ligand, a cytokine necessary for osteoclast formation and function. Unlike bisphosphonates, which bind avidly to hydroxyapatite and have a long half-life in bone, the effect of these two monoclonal antibodies is transient.

In phase 2 trials of denosumab, the gain in bone mass with two years of treatment was completely lost after one year off therapy.3 Markers of bone resorption increased after denosumab discontinuation to levels higher than baseline, suggesting a hyperresorptive state. McClung et al.4 found that bone mineral density in the lumbar spine had increased 16.8% after eight years of denosumab therapy but declined 6.7% in the first year after stopping.

Some have described the dramatic decline in bone mass as if bone were a “spring,” (i.e., when pressure is released, the material wants to rebound to the pretreatment state). Finite element analysis, a measure of bone strength, was shown to increase with denosumab treatment in the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) trial.5

Since fracture risk increases rapidly after denosumab discontinuation and multiple vertebral fractures occur with greater frequency, it is important to track patients who miss their scheduled injections. Further, if patients must discontinue denosumab (e.g., because of adverse effects), another osteoporosis medication should be initiated to prevent bone loss and prevent fracture.

Advertisement

In the Denosumab Adherence Preference Satisfaction (DAPS) study, 115 of 126 patients randomized to denosumab for 12 months were transitioned to alendronate for 12 months; 15.9%, 7.6% and 21.7% lost bone mineral density in the lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck, respectively.11

In six patients who discontinued denosumab after seven years and received one dose of zoledronate, bone mineral density declined in both the lumbar spine and hip at 18 to 23 months after infusion.12 Bone mineral density remained significantly higher than baseline in the lumbar spine but declined to pretreatment levels in the hip. The authors suggested that more than one dose of zoledronate might be more effective for preventing bone loss.

The timing of administration of zoledronate may be important. Data suggest that if bone turnover is very low, bisphosphonate binding to bone may be reduced, and this lessens its efficacy in preventing bone loss. The ZOLARMAB trial (Treatment With Zoledronic Acid Subsequent to Denosumab in Oteoporosis, clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03087851) has enrolled 60 patients in three arms, i.e., receiving a dose of zoledronate at either six or nine months after denosumab discontinuation, or when a marker of bone resorption rises above a prespecified level. A second dose of zoledronate is given in patients who have a decline in bone mineral density or an increase in a marker of bone resorption. Results are expected in 2020 or 2021.

Given the risks associated with discontinuation, should we continue to prescribe denosumab? The answer is that denosumab clearly has a place in therapy for patients at high risk of fracture. Bisphosphonates are not recommended if the glomerular filtration rate is less than 35 mL/min/1.73 m2. Since denosumab is excreted by the reticuloendothelial system and not the kidney, it is preferred in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Advertisement

Many patients do not tolerate oral bisphosphonates because of gastrointestinal adverse effects or bone pain. With bisphosphonate therapy, increases in bone mass occur in the first three years of therapy, after which no further increases occur. Denosumab is unique in that increases in bone mass continue through 10 years of treatment. Analysis of the FREEDOM extension showed that the incidence of nonvertebral fractures was lower with higher total hip T scores achieved with treatment.13 For these reasons denosumab will continue to have an important place in the treatment of patients with low bone mass. For those who must discontinue denosumab, a bisphosphonate is recommended. More information is needed on oral or intravenous bisphosphonate therapy and the appropriate timing of therapy after denosumab discontinuation.

As a result of the current COVID-19 pandemic, there is a higher likelihood that patients will miss scheduled denosumab treatments. Many patients are appropriately wary about coming for an appointment, so it is incumbent on providers to make patients understand the risks of discontinuation.

Many assisted-living facilities and nursing homes do not want residents to go to “routine” healthcare visits. Whenever possible, we should encourage these facilities to administer denosumab to their residents and make financial considerations secondary. If a family member is a healthcare provider, an attempt should be made to have the drug administered at home, if possible.

We should go the extra mile to make sure our patients get appropriate treatment. If all else fails, an oral bisphosphonate should be started, and denosumab can be resumed at a later date.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being