Updated guidance on identification and strategies for management

By Oltion Mesi, MD; Charlie Lin, MD; Haitham Ahmed, MD, MPH; and Leslie Cho, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This article is an abridged and adapted version of a review published in the July 2021 issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2021;88:381-387). For the full-length, fully referenced version, see the open-access article on the journal’s website.

With a proven track record in reducing morbidity and mortality related to atherosclerotic disease, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are first-line cholesterol-lowering medications. However, many patients experience musculoskeletal side effects — myopathy, myalgia, myositis and, rarely, rhabdomyolysis — that either prevent them from using statins at all or limit their ability to tolerate a dosage necessary to achieve their cholesterol targets. As suboptimal control keeps them at continued cardiovascular risk, such patients should be thoroughly evaluated for true statin intolerance, and adjunctive or alternative therapies should be considered.

A major difficulty in establishing statin intolerance lies in distinguishing statin-associated from nonstatin-associated muscle symptoms. Many patients diagnosed with statin-associated muscle symptoms likely have nonspecific musculoskeletal pain that is unrelated to statin therapy. Although the Statin-Associated Muscle Symptom Clinical Index questionnaire was designed to facilitate diagnosis, it requires additional validation.

Whereas previous trials have suggested an almost indistinguishable side-effect profile between low-dose statin therapy and placebo, more recent rechallenge crossover studies such as the GAUSS-3 and ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trials have been able to establish statin intolerance as a real and verifiable phenomenon.

Advertisement

For instance, the GAUSS-3 trial used a double-crossover design with atorvastatin and placebo in 491 patients who were self-reported to be intolerant to two or more statins. It found a 43% rate of true statin intolerance, determined by symptoms present during atorvastatin therapy but absent during placebo therapy. Although similar rates of myalgia were reported initially in the atorvastatin and placebo groups, after full completion of the washout and double-crossover protocol, significantly more patients experienced muscle-related symptoms when taking atorvastatin than when taking placebo (hazard ratio = 1.96; 95% CI, 1.44-2.66; P < 0.001).

Confirm statin intolerance. In a patient suspected of having statin intolerance, statin therapy should be discontinued and symptoms monitored over two weeks to see if they resolve. Patients should be asked about alcohol intake and nutraceutical medications, as they potentially contribute to and confound muscle symptoms attributed to statins. After two weeks, if symptoms have resolved, the same statin can be restarted at a lower dose or an alternative statin prescribed.

Strategies for treating statin intolerance include using an alternative statin, modifying dosage, changing diet and using other medications.

Try another statin. Pharmacologic profiles can differ significantly among statins:

Advertisement

Changing from a lipophilic to a hydrophilic statin is a reasonable first-line alternative drug strategy for patients experiencing myalgia.

Adjust dosage. Intermittent rather than daily dosing can also be considered for patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms and for patients who have a history of severe myotoxicities and marked creatine kinase elevation.

Studies have found that intermittent dosing can achieve low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) reductions of about 20% to 40%, although impacts on cardiovascular outcomes have yet to be established. A large single-center study of statin-intolerant patients found a trend toward mortality benefit with intermittent dosing. A statin with a long half-life, such as rosuvastatin, may be a good choice for intermittent dosing.

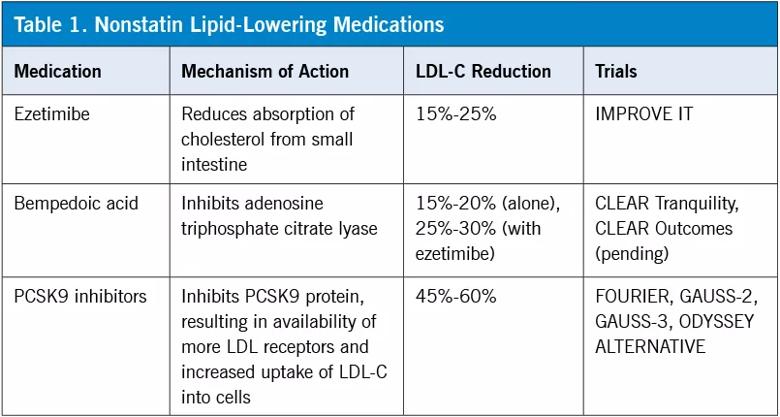

For patients with persistent symptoms even after trials of two different statins at their lowest dosages, categorical intolerance is likely, and nonstatin medications should be considered. These include ezetimibe, bempedoic acid and PCSK9 inhibitors. The actions of these agents are summarized in Table 1.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/bcf61483-8736-440d-875d-79ab034efc1d/21-HVI-2500365-Table-Inset-805x430-1_jpg)

PCSK9 inhibitor therapy. Monoclonal antibody PCSK9 inhibitors have been reported to reduce LDL-C concentrations by up to 60% and reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. Several studies have evaluated the efficacy of PCSK9 inhibitors in patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms.

The GAUSS-2 trial randomized more than 300 patients who experienced statin-associated muscle symptoms and discontinued two different statins to either evolocumab (a PCSK9 inhibitor), ezetimibe or placebo. After 12 weeks of therapy, evolocumab was associated with the largest average reduction in LDL-C from baseline values, 56.1% (P < 0.001). None of the patients in the evolocumab group discontinued medication due to muscle-related events.

Advertisement

The GAUSS-3 trial randomized confirmed statin-intolerant subjects to evolocumab or ezetimibe for 24 weeks. Evolocumab produced a 52.8% mean reduction in LDL-C from baseline values compared with a 16.7% mean reduction with ezetimibe (P < 0.001). Discontinuation of therapy due to muscle-related symptoms occurred in 6.8% of the ezetimibe group versus 0.7% of the evolocumab group.

The ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trial compared PCSK9 inhibitor therapy (using alirocumab) with ezetimibe in patients with confirmed statin intolerance. While ezetimibe reduced mean LDL-C by 14.6%, alirocumab reduced mean LDL-C levels by 45.0%. Muscle-related symptoms occurred less frequently with alirocumab (32.5%) than with ezetimibe (41.1%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

These findings establish PCSK9 inhibitor therapy as a promising alternative LDL-C lowering strategy in patients with proven statin intolerance. It may ultimately prove superior to statin dosage reduction, dietary modification and pharmaceutical alternatives.

Bempedoic acid.In 2020, the FDA approved bempedoic acid for treatment of hypercholesterolemia. It works by inhibiting adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase (ACL), an enzyme critical to the hepatic synthesis of cholesterol.

In the CLEAR Tranquility phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial of patients with a history of statin intolerance, bempedoic acid together with ezetimibe led to an LDL-C reduction of 28.5% more than ezetimibe alone (P < 0.001), while bempedoic acid led to significant reductions in non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (23.6%), total cholesterol (18%), apolipoprotein B (19.3%) and C-reactive protein (31%) (P < 0.001).

Advertisement

The ongoing CLEAR Outcomes study is randomizing more than 14,000 patients who are statin-intolerant and at high risk for cardiovascular disease to treatment with bempedoic acid versus placebo. Results are expected in 2023 to address the effects on cardiovascular outcomes.

While PCSK9 inhibitor therapies and bempedoic acid will likely find their way into routine prescription use in the coming years, ongoing investigations continue to demonstrate promise from other advanced lipid-lowering approaches.

Inclisiran, currently under FDA review, is a small interfering RNA (siRNA) agent that inhibits translation of the PCSK9 protein and therefore its formation. This promotes LDL-C receptor recycling from cell membranes at a stage upstream from the PCSK9 inhibitor therapies. Trials of patients with elevated LDL-C levels despite maximally tolerated statin therapy found that adding inclisiran reduced LDL-C levels by about 50% compared with baseline levels of patients on statin therapy only. Inclisiran is administered by subcutaneous injection, followed by a second dose after 90 days and subsequent doses every six months thereafter.

Evinacumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3), a protein that inhibits lipoprotein lipase and thereby increases plasma LDL-C levels. Gene mutations resulting in loss of function of this protein are associated with hypolipidemia. A phase 3 clinical trial with 65 patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia found that evinacumab infusion every four weeks reduced LDL-C by 49 percentage points versus the placebo group at 24 weeks, with both groups also on maximum lipid-lowering therapy.

Gene editing. Finally, recent evidence from nonhuman primates shows promise in the field of gene editing, a form of next-generation alteration of the biological blueprint that underlies serum lipoprotein concentrations. Gene therapy to mimic natural cardioprotective variants (such as targeted reduction in PCSK9 and ANGPTL3 protein production) has shown reduction in serum cholesterol levels.

Nutraceuticals are natural food-derived substances that are generally well tolerated and provide health benefits, including the prevention or treatment of medical conditions. Two of the most widely studied in cardiovascular medicine are red yeast rice (which contains monacolin K, the active ingredient of lovastatin) and berberine. Other plant sterols, soluble fibers, probiotics, polyunsaturated fatty acids and antioxidants have also been evaluated. Lipid-lowering effects occur via multiple mechanisms (e.g., inhibition of the intestinal absorption of cholesterol, inhibition of cholesterol synthesis and enhanced excretion of LDL-C).

Nutraceuticals have been found to lower LDL-C when used alone or combined with ezetimibe or a reduced statin dosage and can help patients with statin intolerance achieve their LDL-C goal. Red yeast rice was found to reduce LDL-C by up to 27% compared with placebo after one to three months.

However, LDL-C reductions are modest compared with pharmacologic therapy, and the long-term effect on cardiovascular outcomes with nutraceutical therapy has not been formally evaluated. Therefore, nutraceuticals should be reserved for patients who are truly statin-intolerant as an adjunct to nonstatin pharmacologic therapy.

“Statin intolerance is a highly controversial topic,” says Steven Nissen, MD, Chief Academic Officer of Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute, in response to this review. “Some prominent clinical trialists have claimed that this disorder does not exist. Their opinion is based on large randomized clinical trials of statins that reported a very low rate of discontinuation due to adverse effects. They also point to recent studies showing no difference in myalgias between placebo and statins. A pragmatic view makes the most sense to me. We should try our best to get patients to take these drugs because the benefits on morbidity and mortality are well-established. However, patients often tell us they simply will not take a statin. For these patients, Dr. Cho and colleagues provide a nice road map for management. Her approach is systematic and highly effective.”

References are available in the full-length version of this article in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2021;88:381-387).

NOTE: Dr. Cho has disclosed conducting research for Amgen, Novartis, Esperion and AstraZeneca, as well as consulting for Amgen, Esperion and AstraZeneca. The other authors report no relevant financial relationships that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest in the context of this article.

Drs. Mesi and Lin were residents in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of General Internal Medicine when this article was written. Dr. Ahmed is a cardiologist with AdvantageCare Physicians, New York, New York. Dr. Cho is Section Head of Preventive Cardiology and Cardiac Rehabilitation in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiovascular Medicine.

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more