It's time to increase testing for this major cardiovascular risk factor in advance of new therapies

Once a week, Steven Nissen, MD, has a clinic in which almost every patient has elevated levels of lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). Patients come to this clinic from around the world, yet their profiles are highly similar: Most have had multiple family members suffer a myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke — and/or undergo bypass surgery or coronary stent placement — by their 40s or 50s.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“These patients typically tell us, ‘I just had my Lp(a) checked and it’s really high; I’m scared to death,’” relates Dr. Nissen, Chief Academic Officer for Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute. He adds that while there are currently no FDA-approved therapies for lowering Lp(a) levels, there are now four promising investigational therapies in clinical trials, and Cleveland Clinic is leading several of those trials.

“We are a focal point for much of the research into treating Lp(a)-related cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Nissen says, “and we are advocates for patients getting their Lp(a) levels checked. In addition to raising awareness of Lp(a) as an important risk factor, this identifies individuals at elevated risk of cardiovascular events so we can treat all their other risk factors super aggressively and consider enrollment in a clinical trial of an investigational therapy if appropriate.”

Dr. Nissen and his Cleveland Clinic colleagues are increasingly focused on Lp(a) because of the emergence of promising investigational therapies and because the clinical impacts of Lp(a) elevation, although once underappreciated, have grown increasingly apparent in recent years.

Those impacts manifest as a heightened risk — and often an accelerated course — of cardiovascular disease, particularly premature MI, venous thromboembolism and calcific aortic stenosis. “Elevated Lp(a) can nearly double the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis,” Dr. Nissen says, “and it tends to lead to disease at a younger age.”

Advertisement

Elevated Lp(a) is a genetically determined risk factor, and there is no evidence that Lp(a) level changes over the course of a lifetime. Normal Lp(a) levels are less than 25 mg/dL. Significant risk of atherothrombotic events begins at levels between 50 and 70 mg/dL and rises thereafter. And that risk is quite prevalent: 64 million U.S. residents have an Lp(a) level of 60 mg/dL or higher. Over 3 million have levels of 180 mg/dL or greater, which confer extremely high risk.

“Lp(a) is an important cause of early and aggressive coronary disease, particularly in individuals without other traditional cardiovascular risk factors,” says Luke Laffin, MD, a staff cardiologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Section of Preventive Cardiology. “We have no FDA-approved therapies to reduce Lp(a) and its related cardiac risk, so this has been a substantial challenge we’ve been unable to treat.”

Indeed, Lp(a) levels are unaffected by available lipid-lowering therapies or by lifestyle interventions. “Elevated lipoprotein(a) is one of the last untreatable frontiers of cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Nissen notes.

That may soon change, however, in view of the development of several investigational therapies known collectively as nucleic acid therapeutics.

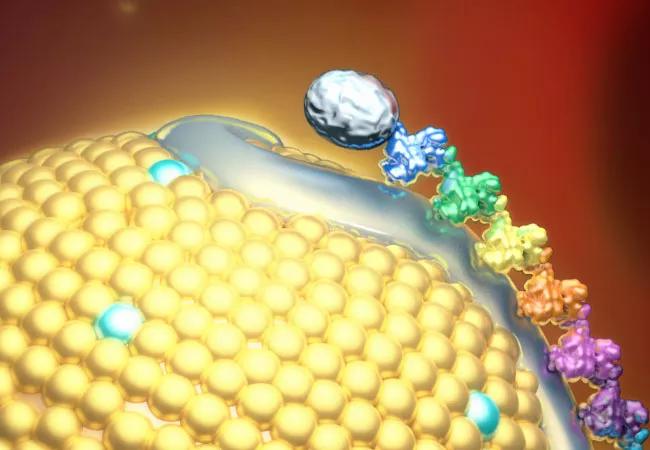

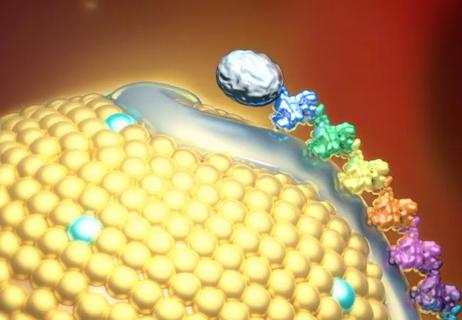

To best understand these therapies, it’s helpful to review a few Lp(a) essentials. Lp(a) is a variant of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) that contains an atherogenic component, apolipoprotein B100, and a prothrombotic component, apolipoprotein(a). Elevated blood Lp(a) levels are mostly due to genetic variations in the LPA gene that encodes apolipoprotein(a). Nucleic acid therapeutics are designed to silence the LPA gene to reduce elevated Lp(a) levels and their harmful effects.

Advertisement

There are two classes of nucleic acid therapeutics — antisense oligonucleotides and short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) — that both act by degrading the messenger RNA that codes for apolipoprotein(a). Both conjugate with N-acetyl-galactosamine (GalNAc), a sugar that binds to receptors in hepatocytes. This concentrates the therapeutic in the liver, where it blocks the synthesis of apolipoprotein(a) required for Lp(a) formation and minimizes its presence in the circulation.

Four nucleic acid therapeutics — all administered subcutaneously — are now in clinical testing, as follows:

Lepodisiran is particularly intriguing, says Dr. Nissen, who presented results of a phase 1 trial of the agent at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2023 (also published in JAMA. 2023;330:2075-2083). “A single dose of lepodisiran lowered Lp(a) to a level undetectable by the standard assay from day 29 to day 281 following administration, and to a level 94% below baseline at the end of the 48-week study,” he says. “This is an unprecedented degree and duration of Lp(a) reduction, which suggests lepodisiran could potentially be given once or twice a year, like a vaccine.”

Advertisement

Because the Lp(a) HORIZON and OCEAN(a) studies are both outcome trials, they should help determine whether significant Lp(a) lowering reduces major adverse cardiovascular events in individuals with Lp(a) elevation, as well as the magnitude of Lp(a) reduction needed to yield event reduction.

Since no large trials have previously assessed the effects of Lp(a) reduction, this new wave of studies — some of which are international — will also likely yield insights into potential differential effects in different patient subpopulations.

In fact, insights are still emerging on how Lp(a) levels themselves may differ among various groups prior to any treatment. Cleveland Clinic investigators recently bolstered these insights by publishing findings from Lp(a) HERITAGE (Open Heart. 2022;9:e002060), the first large study to report Lp(a) and LDL cholesterol levels in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) from an ethnically and regionally varied global population.

This 48,000-patient, six-continent epidemiological study found that median Lp(a) levels were highest in patients who were Black, female or younger than 65 years old. It also revealed important public health findings that applied across the entire cohort:

Advertisement

“The vast majority of patients with ASCVD worldwide are being managed without knowledge of their Lp(a) levels even though over a quarter are at heightened risk because of their Lp(a),” observes Leslie Cho, MD, Co-Section Head of Preventive Cardiology at Cleveland Clinic and a study co-author. “These findings underscore the need for major global educational efforts to promote Lp(a) measurement in routine clinical practice. The emerging therapeutics for Lp(a) reduction can only improve outcomes if physicians are aware of their patients’ Lp(a) levels.”

“We want clinicians to start assessing Lp(a) now so that when Lp(a)-targeted therapies become available, we’ll be ready to treat the patients who need them,” Dr. Nissen concludes.

Advertisement

Yet 21.4% of tested individuals had Lp(a) elevation

Small interfering RNA lowered lipoprotein(a) by 94% during six-month follow-up after a single dose

Phase 2 trial of zerlasiran yields first demonstration of longer effect with each dose of an siRNA

Undetectable levels achieved for nearly nine months in phase 1 trial

First-in-human phase 1 trial induced loss of function in gene that codes for ANGPTL3

Proteins related to altered immune response are potential biomarkers of the rare AD variant

Phase 3 TANDEM study may help pave way to first approval of a CETP inhibitor

Resourceful approaches to the care of patients with microvascular disease and elevated Lp(a)