Top "aha moments" in corneal wound healing

A Southern California college student in the early 1970s, Steve Wilson was fascinated by song lyrics. He wrote some of his own, winning an honorable mention at the American Song Festival in Los Angeles as well as the attention of a few minor rock bands.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Now nearly 50 years later, the name Steven E. Wilson graces the covers of multiple award-winning adventure-thriller novels.

But what this prolific writer penned in between is likely his greatest work.

Steven E. Wilson, MD, a refractive and corneal surgeon and Director of Corneal Research at Cole Eye Institute, has authored more than 250 peer-reviewed publications and book chapters, earning him one of the highest Google h-indexes of any ophthalmologist in the U.S. His seminal study on keratocyte apoptosis in corneal epithelial injury, published in Experimental Eye Research in 1996, has been cited more than 450 times.

Funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants for nearly 30 years, Dr. Wilson has been named one of the most influential doctors in cataract and refractive surgery as well as a lengthy list of other distinctions. This year, he has been tapped for the José I. Barraquer Lecture and Award, to be presented at the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) annual meeting in November. The International Society of Refractive Surgery presents this honor each year to a physician who has “made significant contributions in the field of refractive surgery.”

In this Q&A, Dr. Wilson talks about his storied career, including his early days in ophthalmology and his lab’s top “aha moments.”

Q: What attracted you to corneal and refractive surgery?

Dr. Wilson: When I was an ophthalmology resident at Mayo Clinic in the ’80s, I worked alongside William Bourne, MD, renowned for his work in corneal tissue preservation for transplant. He had trained with Herbert Kaufman, MD, the longtime chair of LSU Eye Center in New Orleans, a phenomenon in corneal and refractive surgery.

Advertisement

I decided to follow in Dr. Bourne’s footsteps and apply at Louisiana State for a cornea/refractive fellowship, so I went down to New Orleans to interview with Dr. Kaufman. At the end of the interview, he offered me a position. I thanked him but told him that I hadn’t interviewed anywhere else yet. He told me I had two days to decide.

I took his offer and never looked back. I never regretted going to LSU Eye Center, which did some of the first photorefractive keratectomies (PRKs) in the world. Marguerite McDonald, MD, headed the team that first used the excimer laser. Lots of other innovations were going on there as well. Stephen Klyce, PhD, now one of my best friends, invented corneal topography. I published more than 15 papers with him during and after my fellowship.

My first job after fellowship was at University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. They didn’t have an excimer laser at the time, so I did pure cornea and cataract surgeries for five years.

In 1995, Cleveland Clinic recruited me. At that point, I had 2.5 NIH (R01) grants but hadn’t done much refractive surgery since my fellowship. Three weeks before I arrived in Cleveland, I got the call that Cleveland Clinic’s refractive surgeon was leaving, and they wanted me to take over the program. I agreed to do it, as long as I could still get my research done.

It turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to me. Refractive surgery and corneal wound healing research were a perfect pairing. In large part, it has steered the direction of our work in the lab.

Advertisement

Q: How did corneal wound healing become your research focus?

Dr. Wilson: Before medical school, I pursued a PhD in molecular and cellular biology. I ended up leaving with my master’s degree because I didn’t think I liked research that much — probably because I had experimented with thousands of Drosophila fruit flies. I later thought I could apply that background to the cornea and find my niche in corneal research.

My first R01 grant was looking at growth factors in human endothelial cells. We wanted to learn why the cells don’t normally proliferate (unlike in rabbits, where endothelial cells repair themselves). My lab discovered checks in the human cells and studied how to overcome these checks to get the cells to proliferate.

Over the years, we’ve published hundreds of papers primarily related to corneal stromal-epithelial interactions and growth factors. The top-rated one is still our original description of how damage to the corneal epithelium causes the underlying stromal keratocytes to undergo apoptosis.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5c9a718b-f048-4bf5-894f-a18b0ce1878d/20-EYE-1875141-CQD-QA-Research-and-Barraquer-Award-Inset-1-300x173_jpg)

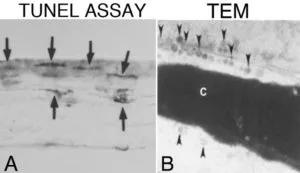

Original images published of keratocyte apoptosis in response to epithelial injury in the mouse cornea. A. At 4 hours after epithelial scrape injury in the mouse cornea, keratocytes in the anterior stroma stain with the TUNEL assay for apoptosis. Mag: 200X. B. Transmission electron microscopy in a mouse cornea at 1 hour after epithelial scrape injury shows classic signs of apoptosis, including condensation of the chromatin (c) and the formation of thousands of “apoptotic bodies” (arrowheads) that contain the cytoplasmic contents of a keratocyte dying by apoptotic programmed cell death. Mag: 30,000X. Reprinted with permission. Wilson SE, et al., Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:325-8.

Advertisement

Before that, people didn’t think keratocytes did much more than maintain collagen in the cornea. Our paper changed that.

But we have 10 more papers in press right now, and this summer we will publish two articles that I’m convinced will one day become our most-cited papers.

Q: What will you discuss in your Barraquer lecture at the AAO annual meeting this fall?

Dr. Wilson: I’m going to highlight my lab’s top “aha moments” over the decades — all related to corneal wound healing and refractive surgery. Of course, keratocyte apoptosis is one. Other notable discoveries include:

I credit the amazing work of my postdoctoral fellows for all of these achievements. None of it would have been possible without their working 40-60 hours per week alongside me.

Q: What is your lab working on today?

Dr. Wilson: We have one R01 grant focused on defective regeneration of the corneal epithelial basement membrane and how it regulates transforming growth factor beta (TGF-ß), which is a major factor in scarring corneal fibrosis.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5cefd531-704f-4572-b6a0-6950ec3c734d/20-EYE-1875141-CQD-QA-Research-and-Barraquer-Award-Inset-2-300x81_jpg)

Myofibroblast development in the anterior stroma after -9D PRK. A. Control cornea shows no myofibroblasts stained for the alpha-smooth muscle actin marker. B. A rabbit cornea at 1 month after -4.5D moderate-correction PRK shows only a single myofibroblast has developed (arrow, red stained cell). C. A rabbit cornea at one month after -9D high-correction PRK shows many myofibroblasts in the anterior stroma (arrows). Blue is nuclei of all cells stained with DAPI. Mag: 200X.

Advertisement

We also have a Department of Defense grant that is funding our work on regenerating Descemet’s membrane after endothelial injury.

Q: How has your work as a researcher made you a better clinician?

Dr. Wilson: Currently, 60% of my time is spent in the lab and 40% in the clinic, split between refractive surgery and medical cornea patients.

As a scientist, I know that more thoroughly understanding a patient’s health problem leads to more rational and effective treatment. Most of my research projects have derived from encounters with patients.

For example, in the 1990s, I had three patients with Mooren’s corneal ulcers. We discovered that all three had an underlying hepatitis C infection. That spawned research that eventually revealed that antibodies against hepatitis C form complexes that trigger an inflammatory reaction that melts the peripheral cornea. We treated these patients for hepatitis C, and their corneal problems disappeared. Even though we later discovered that less than 5% of Mooren’s corneal ulcer patients have hepatitis C, this provided a paradigm for how underlying disorders can cause these severe peripheral corneal ulcers.

When you learn something novel, it can be exciting not just for ophthalmic care but for the rest of the medical world too.

Q: When and why did you become a novelist?

Dr. Wilson: Over the years, I read a lot of novels while traveling around the world to medical conferences. There came a time when I thought I could write them as well or better than the authors I was reading.

The first novel I wrote — about an ophthalmologist wrongly convicted of murdering his wife — was never published. A few years later, I wrote Winter in Kandahar, an adventure thriller told from the perspective of an Afghan fighter post-9/11. It was published in 2003 and won the Benjamin Franklin Award for best new voice in fiction.

That book became the first in a trilogy. The last part, The Benghazi Affair, won the Benjamin Franklin Award for fiction audiobook of the year in 2019.

Also in 2019, I published a memoir, The Making, Breaking and Renewal of a Surgeon-Scientist, which currently is a finalist for nonfiction audiobook of the year.

Doing the research necessary to write a historical novel has a lot of similarities to the research needed to write an NIH grant or a scientific paper. I’ve found both to be highly rewarding.

Advertisement

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

Treatment options range from tetracycline injections to fat repositioning and cheek lift