Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3de21ee8-88c4-43a4-b213-4ea5e78fd3c9/650x450-Vintage-Poster-Venereal-Disease-STD_jpg)

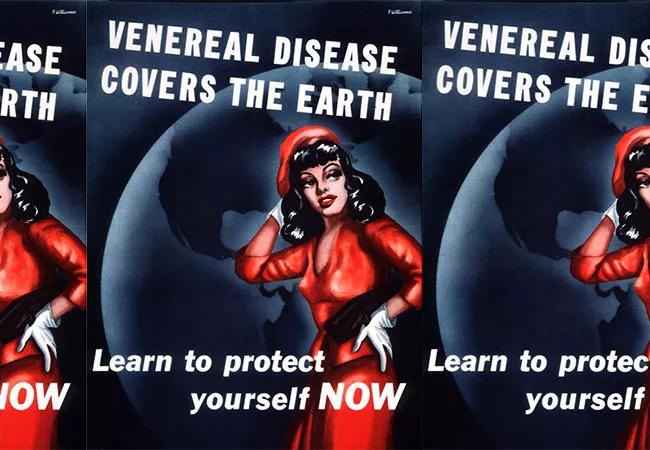

650×450-Vintage-Poster-Venereal-Disease-STD

By Kristin Englund, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

According to a report from the CDC on the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), the total cases reported in 2015 reached the highest number since the CDC was founded in July 1946.

Nearly 24,000 cases of primary and secondary syphilis were reported in 2015, a 19 percent increase from the previous year. And Jonathan Mermin, MD, MPH, Director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, reported, “STD rates are rising, and many of the country’s systems for preventing STDs have eroded. We must mobilize, rebuild, and expand services.”

Dr. Mermin stressed the need to rebuild services because, “In recent years more than half of state and local STD programs have experienced budget cuts… Fewer clinics mean reduced access to STD testing and treatment…”

The CDC has identified several players whose engagement is necessary to stem the tide of this epidemic:

Advertisement

This message sounds familiar. The book No Magic Bullet by Allan M. Brandt provides fascinating details about the World War I period in America’s battle against venereal diseases.

In the late 1910s, antivenereal campaigns were in full swing to train soldiers about STD symptoms and prevention to keep them physically healthy. Similar information was widely available stateside for both men and women in open, matter-of-fact formats.

After the war ended, the national sentiment became split between sexual revolution and social moralism. But the antivenereal campaigns that had been appropriate in wartime came to be considered amoral and unfit for public consumption, and a period of silence about venereal diseases ensued.

By the 1930s, the situation had worsened:

Although penicillin was still a decade or more away from discovery, syphilis could be treated, though likely not cured, with arsenic compounds. A course of treatment from a private physician, however, could cost from $300 to $1,000. Many patients who could not pay these exorbitant prices turned to public clinics for help. However, funding for the Venereal Disease Division of the Public Health Service, originally $4 million in 1920, was cut to less than $60,000 by 1926. Some hospitals refused to admit patients with syphilis and other venereal diseases, deeming them “morally tainted and less deserving of care.”

Advertisement

Dr. Thomas Parran was the New York State health commissioner in 1930, at the start of the Great Depression. Realizing that arguments for moral responsibility to prevent and treat venereal diseases were not effective, Dr. Parran and other public health officials turned to financial arguments. The cost was estimated at more than $100,000,000 annually.

But the general public was not a part of the larger conversation regarding treatment and prevention of syphilis, thanks to the social hygienists. In November 1934, Dr. Parran was scheduled to give a radio broadcast on future goals for public health in New York. Notified that he would not be able to mention syphilis or gonorrhea by name, he refused to give the speech. Dr. Parran went on to lead the charge to reduce the moral cloud that blocked the ability to address syphilis openly and scientifically. With his extensive experience in public health, he proposed plans the following:

Appointed U.S. Surgeon General in 1936, Dr. Parran published “The next great plague to go,”1 an article focusing on the medical approach to treating syphilis and other venereal diseases, while refusing to address the moral and social issues. Two years after he was blocked from mentioning syphilis and gonorrhea on the radio, he was pictured on the cover of Time magazine for his groundbreaking work.

Advertisement

With the advent of penicillin, syphilis became not only treatable but curable. Over the next decades, the number of patients infected with syphilis and the morbidity it caused continually declined until the 1990s, when there were even whispers of eradication in the United States.

However, the 1990s saw a new rise in cases of syphilis. This clearly could not be blamed on the social hygienists; rather, it was likely due to apathy and a decline in public health spending. We are now in a period of rapid rise in STDs.

We have the benefit of antibiotics. We have the benefit of hindsight. What we need is to heed the call to arms of Dr. Mermin, to be inspired by the wisdom of Dr. Parran and to act.

Dr. Englund is staff in the Department of Infectious Disease.

Reference:

This abridged article was originally published in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Emerging evidence suggests a patient-specific approach

Not if they meet at least one criterion for presumptive evidence of immunity

Essential prescribing tips for patients with sulfonamide allergies

Confounding symptoms and a complex medical history prove diagnostically challenging

An updated review of risk factors, management and treatment considerations

OMT may be right for some with Graves’ eye disease

Perserverance may depend on several specifics, including medication type, insurance coverage and medium-term weight loss

Abstinence from combustibles, dependence on vaping