Why timely screening and treatment are needed

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

As a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, I am continually learning from both my patients and from mentoring trainees. One such learning opportunity emerged a few years ago when Dr. Nicola O’Connor, our first year pediatric infectious diseases fellow, and I cared for a 3 ½-month-old child with classic congenital syphilis. Over the last decade the United States has seen a 165% increase in syphilis, a disease forgotten by many, among women of reproductive age. Concurrently, the rate of congenital syphilis in the U.S. has increased to 33.1 cases per 100,000 live births.

Known historically as the “great imitator” due to its varied clinical manifestations, many clinicians today do not include syphilis in their differential diagnosis and fail to recognize classic presentations of the disease. This was the case for our patient.1 Starting at one month of life, he progressively developed symptoms of syphilis. These included a desquamating rash, purulent rhinorrhea, known as snuffles, and perianal condyloma lata. Ultimately, an astute pediatric dermatologist diagnosed congenital syphilis. His syphilis IgG was positive, and his rapid plasma regain (RPR) was reactive at > 1:512 dilution. On evaluation, long bone radiographs showed periostitis and a cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test was reactive. We treated the child in hospital with intravenous penicillin G for 10 days, and at 6 months old he had a negative CSF-VDRL. Serial RPRs were followed on the infant and they became nonreactive. Sadly, congenital syphilis is preventable, yet we had failed to recognize that this mother was at high-risk for syphilis. Despite having screened negative for syphilis early in pregnancy, she became infected late in pregnancy and transmitted syphilis to her child.

Advertisement

Screening during pregnancy identifies women with syphilis, leads to maternal treatment that prevents congenital infection, and limits the need for neonatal evaluations and treatments. In the state of Ohio, syphilis screening is required at the first prenatal visit. For women at high-risk of syphilis, repeat screening should also be performed in the early third trimester and again at delivery to identify new infections or, in the case of those with a history of treated syphilis, to detect reinfection. Inspired to understand the shortcomings of maternal screening for syphilis, Dr. O’Connor made this topic the focus of her fellowship research.

The two types of tests used to screen for syphilis are the nontreponemal and the treponemal tests. Nontreponemal tests do not specifically recognize Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. August Paul von Wasserman first reported in 1906 that antibodies in the serum of patients with syphilis form immune complexes with antigens purified from organs of syphilis infected humans or animals.2 Eventually the antigen was determined to be cardiolipin, a phospholipid. While the syphilis bacterium contains cardiolipin, it has only weak immunogenicity. In response to syphilis infection, anti-phospholipid antibodies increase. This is likely a combined effect of exposure to both the T. pallidum cardiolipin and to host-cell cardiolipin. Since these anti-phospholipid antibodies decline with treatment, they can be used to not only detect infection, but to monitor for treatment response or reinfection. The two nontreponemal antibody tests used today are the VDRL and the RPR. In contrast, treponemal antibody tests specifically recognize antigens on the syphilis bacterium. In general, treponemal antibodies remain positive for life and are not useful in monitoring response to treatment or in detecting reinfection. Common treponemal assays used today include the Syphilis IgG or Syphilis IgG/IgM and the antigenically distinct T. pallidum antibody.

Advertisement

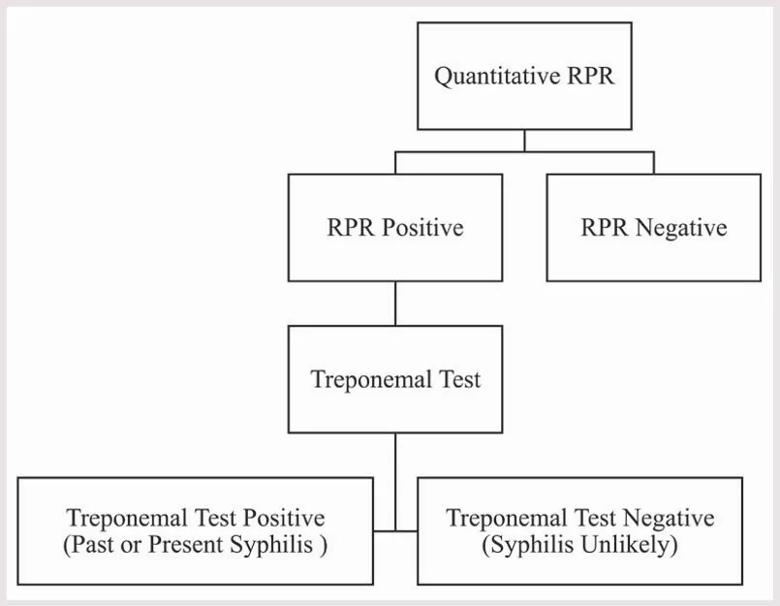

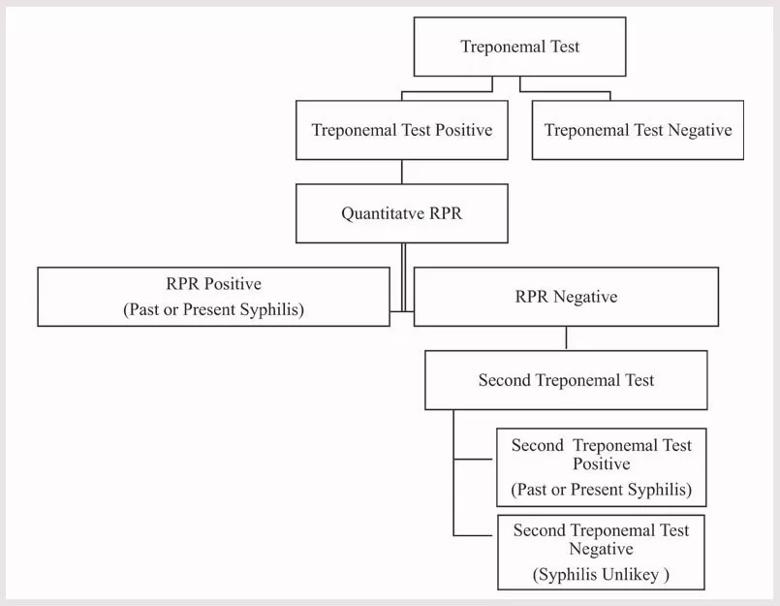

When screening for syphilis, it is necessary to use both a treponemal and a nontreponemal test. In the traditional algorithm (Figure 1), the patient’s blood is screened first with a nontreponemal assay, such as the RPR. As false positive results occur commonly, a positive screening result requires confirmation with a more specific treponemal test, such as the T. pallidum antibody. In the reverse algorithm (Figure 2), the blood sample is screened first with a treponemal assay, such as the syphilis IgG and IgM assay. If the initial screen is positive, the result is confirmed with a nontreponemal test. If the test results are discordant, a second treponemal antibody test, such as the T. pallidum antibody, is used as a tiebreaker.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/08103ba0-4396-4ec8-9689-d9d48328c4cd/22-CHP-3310808-CQD-Ped-Perspectives-Foster-Syphilis-Screening-during-Preg-inset1_jpg)

Figure 1. Traditional syphilis screening algorithm. Reproduced with permission from American Academy of Pediatrics. O’Connor NP, Burke PC, Worley S, Kadkhoda K, Goje O, Foster CB. Outcomes After Positive Syphilis Screening. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b4debea2-3263-4a4e-b32e-10af566b8a6b/22-CHP-3310808-CQD-Ped-Perspectives-Foster-Syphilis-Screening-during-Preg-inset2_jpg)

Figure 2. Reverse syphilis screening algorithm. Reproduced with permission from American Academy of Pediatrics. O’Connor NP, Burke PC, Worley S, Kadkhoda K, Goje O, Foster CB. Outcomes After Positive Syphilis Screening. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3).

In her project, which was recently published in Pediatrics, Dr. O’Connor looked at outcomes of more than 75,000 pregnant women and their delivered children who were screened for syphilis. With both screening algorithms, false positive initial screens were common, 83% overall and for each of the algorithms.3 Her results document the challenges associated with syphilis screening during pregnancy and highlight opportunities for improvement. Overall, there were 243.8 false positive (FP) and 50.6 true positive (TP) screens per 100,000 pregnancies. Of the TP women, 21 (55%) had a past syphilis diagnosis treated before the pregnancy and 17 (45%) had a new diagnosis during the pregnancy. Perhaps reflecting uncertainty over test interpretation, on rare occasions mothers with FP screens and some of their infants received unnecessary evaluations and treatments for syphilis. Among TP women with a new syphilis diagnosis, the diagnosis was early enough during pregnancy to allow for treatment in 93% of case. Despite this, in half of these women there was concern for reinfection, treatment failure, inadequate treatment or follow-up care, or late treatment. In addition, failure to implement risk-based rescreening at delivery resulted in two missed maternal infections and the case of congenital syphilis described above. As women with a history of syphilis are at especially high risk for treatment failure or reinfection, it was concerning that only half of the women treated for syphilis before the pregnancy had a recommended RPR screen at the time of delivery.

Advertisement

Congenital syphilis is a preventable disease but requires timely maternal syphilis screening and treatment in pregnancy.4 Our study highlights the importance of syphilis screening during pregnancy, the need to follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sexually transmitted infection treatment guidelines and the need to educate clinicians in the interpretation of syphilis diagnostic assays.5

About the author: Dr. Foster is Medical Director of Pediatric Infection Prevention at Cleveland Clinic Children’s and Professor of Pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University.

Advertisement

References

1. O’Connor NP, Gonzalez BE, Esper FP, Tamburro J, Kadkhoda K, Foster CB. Congenital syphilis: Missed opportunities and the case for rescreening during pregnancy and at delivery. IDCases. 2020;22:e00964.

2. Hemarajata P. A Brief History of Laboratory Diagnostics for Syphilis. https://asm.org/Articles/2020/January/A-Brief-History-of-Laboratory-Diagnostics-for-Syph. Accessed October 3, 2022.

3. O’Connor NP, Burke PC, Worley S, Kadkhoda K, Goje O, Foster CB. Outcomes After Positive Syphilis Screening. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3).

4. Williams JEP, Graf RJ, Miller CA, Michelow IC, Sanchez PJ. Maternal and Congenital Syphilis: A Call for Improved Diagnostics and Education. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3).

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2021, syphilis during pregnancy. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/STI-guidelines-2021.pdf. Accessed October 3 2022.

Advertisement

Research may offer family-planning insights for those with the condition

Surveyed residents say they get little or no nutritional training

Newer drugs can affect likelihood of pregnancy

Comparing strategies for cesarean prophylaxis with penicillin allergy

A discussion of special care considerations before, during and after pregnancy

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

ACOG-informed guidance considers mothers and babies

Rare pregnancy complication can lead to fetal demise