Computer simulation identifies causes of instability

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6f322346-1b52-4e29-abf4-48b474c8f092/23-ORI-3514158-CQD-650x450-1_jpg)

23-ORI-3514158 CQD 650×450

Patellar injuries, which typically first occur around ages 10-12, can be devastating — causing pain, emotional trauma, and disruption to sports and daily activities. In addition, patellar dislocation at a young age seems to be associated with the development of osteoarthritis later in life.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

For many patients, if patellar dislocation happens once, it’s likely to recur. A new study, using computer-simulated knee injuries, has identified three anatomical factors that are associated with a higher risk of recurrence.

“The findings could help orthopaedic surgeons counsel their patients and guide decisions about when to treat a dislocation with surgery and when to go with nonsurgical intervention,” says Lutul Farrow, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Sports Medicine Center. Dr. Farrow coauthored the study with research scientist John J. Elias, PhD, and orthopaedic resident Jeffrey Watts, MD, both of Cleveland Clinic Akron General.

Just as important, the study also demonstrates the value of using simulations to better understand patellar injuries and other hard-to-study joint issues.

“We now have a model that we can fine-tune to simulate different scenarios and different types of patients that we wouldn’t be able to study in real life or in the biomechanics lab,” says Dr. Farrow.

For the study, published in the Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, the researchers developed 13 computer models of knees with recurring patellar instability, including previous dislocation. Models were based on biomechanics data taken from cadaver research, imaging and other sources.

Researchers used the models to simulate multiple dynamic activities, adjusting different anatomical characteristics to see which ones reduced stability. They identified three factors associated with a higher risk of repeat dislocation, a:

Advertisement

“These are all important factors that predict recurrent instability inside the knee,” says Dr. Farrow.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/738d2583-da63-4bf5-8c76-e72ec2acfdfd/23-ORI-3514158-CQD-Inset-2_jpg)

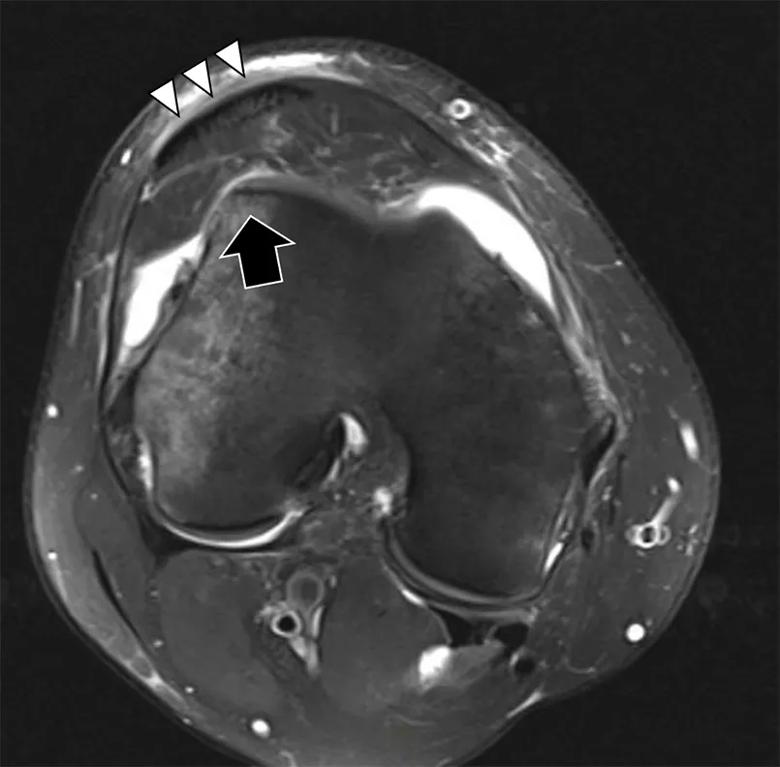

Figure 1. Lateralized tendon. Patellar tendon (triple arrowheads) is displaced 50% over the lateral trochlea (arrow).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d1077926-ab4a-479b-88c0-d331c80a05ad/23-ORI-3514158-CQD-Inset-1_jpg)

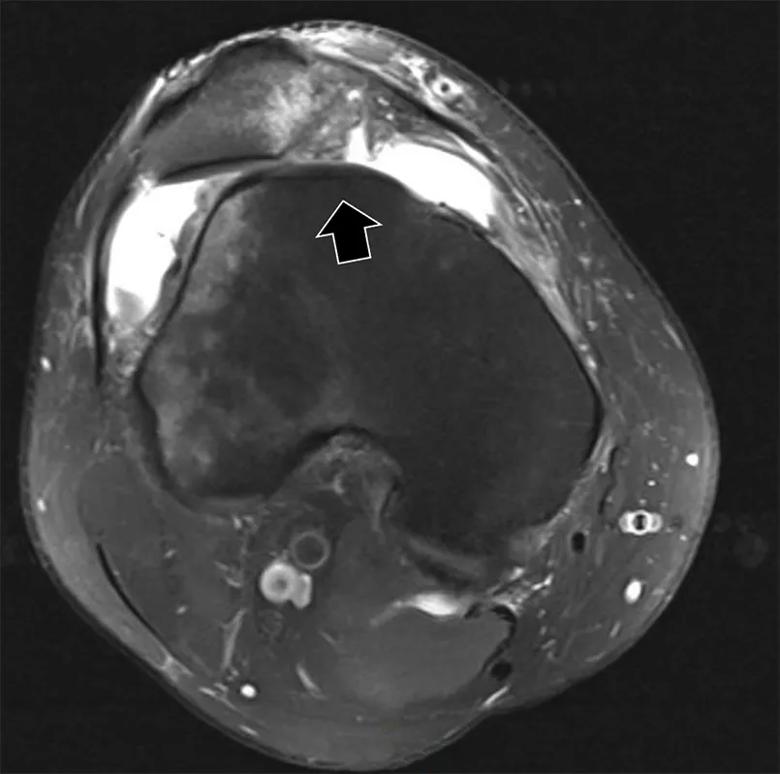

Figure 2. Dysplastic patella. Large arrow demonstrates flat trochlear groove.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/61f28480-858c-448c-927b-d318416580bd/23-ORI-3514158-CQD-Inset-3_jpg)

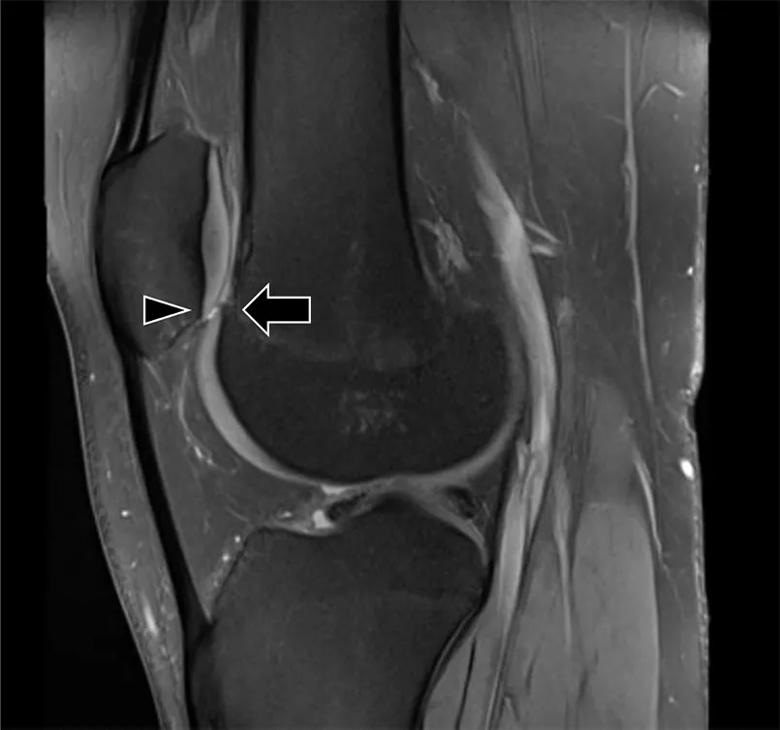

Figure 3. Patella alta. The inferior patellar cartilage (arrowhead) sits above the trochlear articular cartilage (arrow), demonstrating severe patella alta. Normally there is chondral overlap.

The study helps fill a gap in understanding patellar injuries.

“There’s a tremendous amount of literature dedicated to things like the ACL, meniscus and tibiofemoral cartilage issues, but we’ve not been as successful in getting the same kind of information about the patellar joint,” says Dr. Elias.

Computer models offer significant advantages in understanding patellar function and injury, he adds. To date, most research has been done on cadaver knees, which have significant limitations: Specimens might not have the pathology that researchers want to study; cadaver knees can’t be tested during dynamic movements that cause injury; and they’re expensive.

“If you get just eight to 10 specimens for one study, it can be very costly,” says Dr. Elias. “In contrast, with computational models, we can change the anatomy, we can change external forces, we can simulate specific athletic activities, and we can look at lots of different knees.”

The researchers note that the results of their study aren’t surprising, but the findings validate risk factors that many surgeons have observed anecdotally in their patients.

Advertisement

“These findings can help us better counsel our patients,” says Dr. Farrow. “In the past, I may not have recommended surgery for certain patients after a single dislocation. Now I will consider surgery for patients that have a flat trochlea, patella alta and poor rotational alignment. I now can tell these patients that they have a high risk of redislocating their knee.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Youth and open physes are two factors that increase risk of recurrence

How it’s similar but different from the direct anterior approach

Collaboration must cross borders and disciplines

Systematic review of MOON cohorts demonstrates a need for sex-specific rehab protocols

Should surgeons forgo posterior and lateral approaches?

How chiropractors can reduce unnecessary imaging, lower costs and ease the burden on primary care clinicians

Why shifting away from delayed repairs in high-risk athletes could prevent long-term instability and improve outcomes

Multidisciplinary care can make arthroplasty a safe option even for patients with low ejection fraction