Recognizing patient readiness for interventions can be central to success

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Dr. X” was one of the most skilled and highly regarded physicians in his field and a rising clinical star when, in 2008, he noticed a decrease in dexterity of his right arm and some curling of his right foot. He was only 37 years old.

Fearing Parkinson disease (PD), he left his home in Northeast Ohio and sought consultation at a leading academic medical center elsewhere in the country. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of PD was confirmed.

He was first started on levodopa, which resulted in dramatic improvement. Soon, however, the dose had to be increased as he started experiencing wearing-off symptoms. The dose was escalated rapidly, until even the highest dosage could not provide meaningful and lasting benefit. Ropinirole was soon added, up to the highest recommended amount, without much benefit. He was then placed on rasagiline, then pramipexole, then entacapone.

In a short span of two years, he was taking four PD medications around the clock yet was still experiencing tremors, stiffness, predictable wearing off, sudden off spells, foot dystonia and peak-dose dyskinesias. The solution offered was to add more medications. He was then unable to work as a physician and decided to retire and return home to Cleveland with his family.

When Dr. X first presented to me in 2010, he was experiencing every type of motor fluctuation, including levodopa-induced dyskinesias. He was stiff and bradykinetic, with resting tremors in all limbs and postural instability. Within 30 minutes of taking levodopa, his foot curled, his arms started flailing, he began sweating profusely, he was barely audible and his mood dramatically worsened.

Advertisement

My first visit with Dr. X took more than two hours. He needed to understand what motor fluctuations were, how over- and under-medicated states presented, and how some of his symptoms required reducing his medications while others required an increase. These nuances had not been explained to him at his previous facility.

Over the next 12 months, Dr. X’s regimen was simplified, which provided some relief of his wearing-off symptoms, but his dyskinesias remained. He was most bothered by the “off” symptoms, when suddenly he would not be able to speak, walk and sometimes think.

In 2011, we offered deep brain stimulation surgery (DBS) as a potential treatment to relieve him of his wearing-off periods and dyskinesias. He had several concerns, however: What if my personality changes? Can you guarantee success? Will I remain sharp? What exactly will it treat? He was clearly not ready for surgery.

Realizing that wearing off was his biggest problem, I offered him participation in a clinical trial of apomorphine (an injectable dopamine agonist that works quickly, thereby promising to “rescue” him from his off spells). While this provided temporary relief, it became unsustainable when he began requiring several injections per day.

DBS was offered again, but the same fears remained. He asked me if there was any treatment beyond brain surgery or more pills and injections. By 2012, Cleveland Clinic was one of the leading sites testing a then-investigational therapy, levodopa intestinal gel — a liquid form of levodopa delivered directly through the small intestine via an external pump. Dr. X was one of the first patients in Ohio to try this medication, and it was a success. A dramatic improvement in his motor fluctuations was achieved, which sustained him for several years.

Advertisement

However, by 2016, he was again disabled by the motor fluctuations, and this time the dyskinesias were more violent, sometimes displacing him from his chair. He was almost ready for DBS, but he and his family still had questions. I went to his house to meet his wife, children and parents to discuss the procedure and answer all their concerns. Dr. X then met neurosurgeon Andre Machado, MD, PhD, who explained all the technical aspects of DBS implantation surgery.

Dr. X’s case was then presented to the entire movement disorders team in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Neurological Restoration (Figure 1), which collectively concluded that Dr. X was indeed an ideal candidate for DBS surgery.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f044645c-5002-43c7-89a8-1427328dd381/18-NEU-4013-DBS-Parkinson-Meeting_jpg)

Figure 1. A meeting of the Center for Neurological Restoration’s multidisciplinary movement disorders team, including neurologists, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, ethicists, nurses and trainees, to determine if a patient is an ideal candidate for DBS and which type of surgery to offer.

Because of his troublesome dyskinesias, fear of personality change and concern for cognitive impairment, the team felt that the globus pallidus internus (GPi) was a better DBS target than the subthalamic nucleus. Because both sides of his body were equally affected and he was young, otherwise physically healthy and cognitively sharp, the team felt that DBS was best performed bilaterally and simultaneously. But because he was extremely anxious, he was offered DBS under general anesthesia using our intraoperative MRI suite (IMRIS). This state-of-the-art technology, offered by only a few centers in the world, allows precise DBS targeting, while a patient is asleep, with use of an MRI scanner built into the operating room, in contrast to traditional microelectrode recordings that can be performed only when the patient is awake (Figure 2).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/fae29fbf-0bcd-421a-8c40-631cb9ef9b8d/18-NEU-4013-DBS-Parkinson-IMRIS_jpg)

Figure 2. Cleveland Clinic’s intraoperative MRI suite allows precise DBS targeting while the patient is asleep.

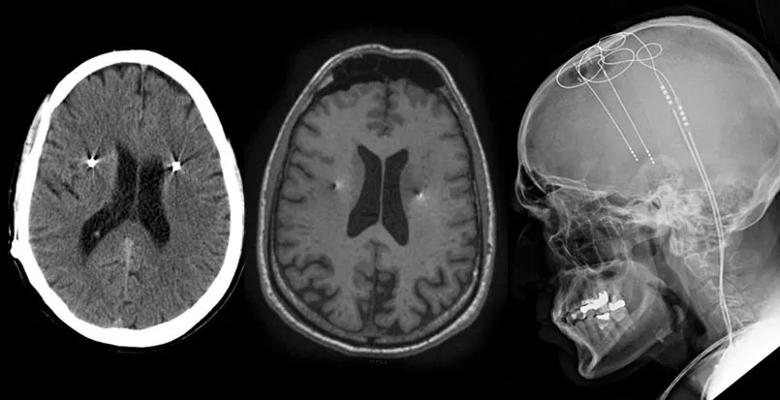

In 2017, seven years after his initial consultation at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. X finally underwent bilateral GPi DBS under general anesthesia (Figures 3 and 4).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/46dfeaed-87a5-45ea-8301-5e042c18c632/18-NEU-4013-DBS-Parkinson-Postoperative_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative imaging of Dr. X showing DBS implantation in the globus pallidus internus.

Three months after adjustment of his DBS settings, Dr. X’s levodopa intestinal gel pump was discontinued and he was converted back to oral levodopa. After two more months, he is now sustained solely on oral levodopa plus amantadine, with almost no wearing-off symptoms, “near normal” motor control (in Dr. X’s own words) and minimal dyskinesias. At our most recent office visit, his wife said, “I have my husband again.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4d62b800-d5f1-4657-b7fd-0459ac479160/18-NEU-4013-DBS-Parkinson-Machado-Surgery_jpg)

Figure 4. Neurosurgeon Andre Machado, MD, PhD, performing globus pallidus internus DBS.

PD is a complicated illness that requires the clinician to listen intently to the patient, as symptoms can stem from any of several causes — the disease itself, lack of medication or too much medication. Because younger patients, like Dr. X, are at a higher risk of developing motor fluctuations, it is even more critical to pay attention to their responses to medication. If not, the result can be an unnecessarily rapid escalation of medication, which then fuels further motor fluctuations in a vicious cycle.

Fortunately, we now have options and our patients live longer and more fulfilling lives. Our Center for Neurological Restoration offers one of the nation’s most recognized clinical trial programs, and Dr. X participated in two of the trials we offered for PD. While this bought him time, after several years, even the best pharmacological treatments have limitations.

Advertisement

DBS is perhaps one of the greatest advances in neurology — and even medicine more broadly — because of its ability to restore motor function in a patient with PD. However, DBS is not for everyone. It is a highly technical procedure that carries its own risks and can be intimidating for any patient.

While Dr. X was likely to have benefited from DBS in the third or fourth year of his illness, he was not emotionally and psychologically ready. Sometimes patients need to go through “the process” at their own pace before finally deciding to go for it. It took me six years, more than 20 visits, enrolling Dr. X in two clinical trials and meeting his family at his house before I was able to convince him the time was right. And it took the collective mind of our entire movement disorders team to determine the best target, staging and surgical procedure that respected and alleviated Dr. X’s concerns. Finally, it took the expertise of a highly experienced neurosurgeon, Dr. Machado, to place the DBS leads in the right target.

Dr. Fernandez is a neurologist and Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Neurological Restoration.

Advertisement

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Rapid innovation is shaping the deep brain stimulation landscape

Study shows short-term behavioral training can yield objective and subjective gains

How we’re efficiently educating patients and care partners about treatment goals, logistics, risks and benefits