Education, lifestyle modifications and new drug therapies can help

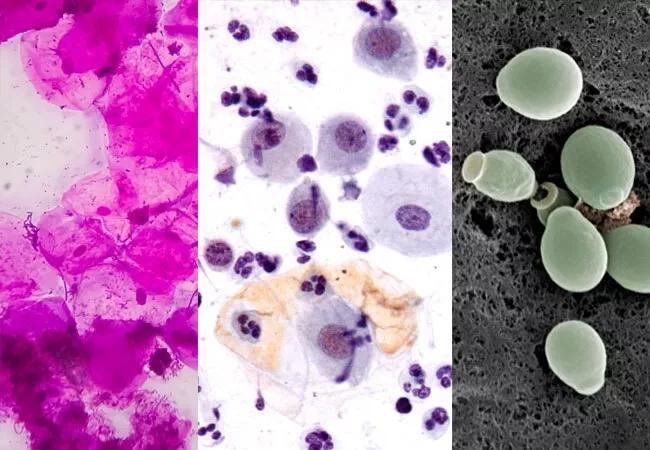

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a17aabdb-92bb-4605-a2b7-2bd8d23b8b9a/21-WHI-2515076_CQD_650x450_combination_jpg)

Vaginitis and the microbiome

Vaginitis is among the most common gynecologic conditions, but it’s not unusual for effective treatment to be unnecessarily delayed. The unspecific nature of vaginitis symptoms (itching, burning, discharge), repeated patient self-treatment, and busy provider schedules all can contribute to delays in diagnosis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Oluwatosin Goje, MD, a OB/GYN and infectious diseases specialist with Cleveland Clinic’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Institute, is coauthor on a recent journal article that highlights causes and treatments of vaginitis. “Microbiome and vulvovaginitis,” published in Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, considers noninfectious and infectious causes, including bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and trichomoniasis.

The authors also stress the vaginal microbiome. Education about the microbiome is important topic, says Dr. Goje, both because treatments that alter the microbiome can be helpful and because talk of the microbiome erroneously leads some patients turn to probiotics for help.

“I tell patients that if they want to take probiotic, it’s fine, but that doesn’t mean that it will fix the vagina,” she says.”

Among takeaways from the report:

Unlike treatments for hypertension, diabetes and other diseases, medications for recurrent gynecologic conditions have not achieved game-changing breakthroughs for chronic vaginitis, says Dr. Goje. “Patients ask me, ‘Is there nothing new? Is it the same thing you’re going to give me?’ We’ve not achieved new strides.”

Advertisement

But newer non-antibiotic therapies hold some promise. In one study of 66 patients, introducing vaginal application of the live bacteria Lactin-V after a standard course of metronidazole significantly reduced the number of recurrent episodes of bacterial vaginosis.

Intravaginal boric acid (IBA) therapy is also commonly used in non-pregnant individuals and found to be safe in the treatment of azole-resistant vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC – yeast) or recurrent BV infection.

For VVC, fluconazole and other vaginal azoles have long been first-line drugs, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still recommends them. But over time, overexposure can lead to drug resistance. When patients report that their treatment isn’t working, Dr. Goje validates their symptoms and runs a fungal culture; fluconazole resistance is sometimes evident.

Azole overexposure can happen when symptomatic patients or providers go repeatedly to these drugs without first confirming the cause. “I tell my patients, if you’ve done Monistat® once and it hasn’t worked, it’s time to make a phone call to your provider,” says Dr. Goje.

In 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved ibrexafungerp, the first oral non-azole for treatment of VVC, and in 2022 the FDA approved the drug for monthly dosing to reduce recurrent VVC. Oteseconazole also was approved in 2022 to prevent recurrent VVC.

“When we talk about management of yeast, we advocate a multifaceted approach to management –pharmacologic therapy, lifestyle modification and education,” says Dr. Goje.

Advertisement

The development of new drugs is an important advance because VVC can carry social and psychological consequences.

“People ask what the big deal is about having a yeast infection,” says Dr. Goje. “If you have a patient who keeps having this every other week, it takes a toll on them. Sometimes people feel ashamed or stigmatized, so they don’t speak up.”

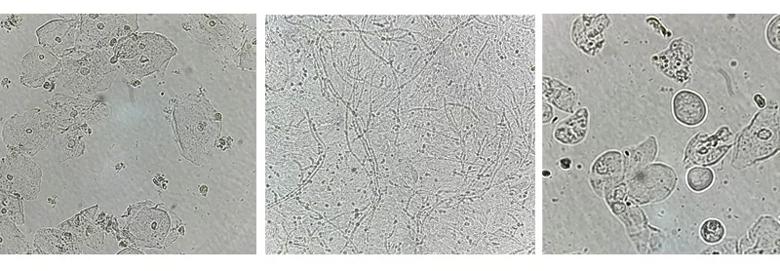

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/88b92be6-2709-4d45-9bb8-e9129aa09c5d/23-WHI-4041260_CQD_Vaginitis_jpg)

From left, microscopy images of a normal vaginal sample, fungal elements of a yeast infection, and atrophic vaginitis.

An estimated 70% of patients with trichomoniasis are asymptomatic – an especially troublesome statistic given that sexual partners can be infected.

“Providers tend to treat empirically versus testing, especially when they’re a small group and they’re very busy. If your patient is not getting better, you need to run a test and consider trichomoniasis,” says Dr. Goje. “Trichomoniasis tends to affect an older age group. With gonorrhea and chlamydia, you tend to see cases in the 20-to-25-year-old age group. But trichomoniasis tends to show up more in the 30s and 40s. So if you have an older patient complaining about vaginal symptoms and you’ve treated for yeast and for BV and they continue to complain, you might want to perform a test looking for trichomoniasis.”

In the absence of evidence of infection, it’s important to remember that non-infectious vaginitis can be a mimic. It is important to validate patients with vaginitis symptoms whose test results are negative. A saline microscopy is needed to evaluate for non-infectious vaginitis. For some, menopause is at the root.

Advertisement

“Not everyone who goes through menopause just has hot flashes. Some people have vaginal dryness so bad that they itch,” says Dr. Goje. “So if a 65-year-old is itchy and you think it’s yeast, and you’ve given her Diflucan® and she’s not getting better, it’s time to consider menopausal atrophic vaginitis. If she burns with urination and she has had 20 negative urine cultures, maybe it’s menopausal atrophic vaginitis.”

Vaginal estrogen is recommended if she has no contraindication to the use of medication.

Although it’s less common, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis should be considered as well. In that case, the vagina is just inflamed and dry for reasons not completely understood. Decreased estrogen associated with perimenopause and menopause can be a factor.

Vaginal hydrocortisone or clindamycin may provide relief.

With today’s faster paced medical environment, non-specialists rarely use microscopy (which requires annual certification) to diagnose vaginitis. However, there are FDA-approved molecular vaginitis panel tests for office use.

“When we consider each of these pathologies, microscopy when available is fast and the gold standard for BV ( Amsel’s criteria), atrophic vaginitis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Microscopy maybe performed to diagnose yeast infection, and when in doubt, a molecular vaginitis panel or fungal culture, which is the gold standard, may be performed,” she says. “Molecular testing (nucleic acid amplification test) is the gold standard for the diagnosis of trichomonas vaginalis.”

Advertisement

Most important, adds Dr. Goje, is that every provider faced with patients who have persistent vaginitis symptoms should consider the full array of possibilities.

“Every time I talk about vaginitis, I want providers to remember to consider menopausal atrophic vaginitis and desquamative vaginitis in the mature female who continues to have symptoms despite negative vaginitis testing.”

Advertisement

Recent research underscores association between BV and sexual activity

Treatment being offered in cases where medical and hormonal management was not successful

Increasing uptake remains a challenge

Multidisciplinary teams work together in in-situ scenarios

Uterine transposition cleared the field for radiation therapy

ACOG-informed guidance considers mothers and babies

Prolapse surgery need not automatically mean hysterectomy

Artesunate ointment shows promise as a non-surgical alternative