Herpetic retinal infection has high rate of recurrence

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/506f5d7b-ab9b-472b-a31a-00a017521a64/20-EYE-1875127-Viral-Infection-Uveitis-CQD_jpg)

20-EYE-1875127-Viral-Infection-Uveitis-CQD

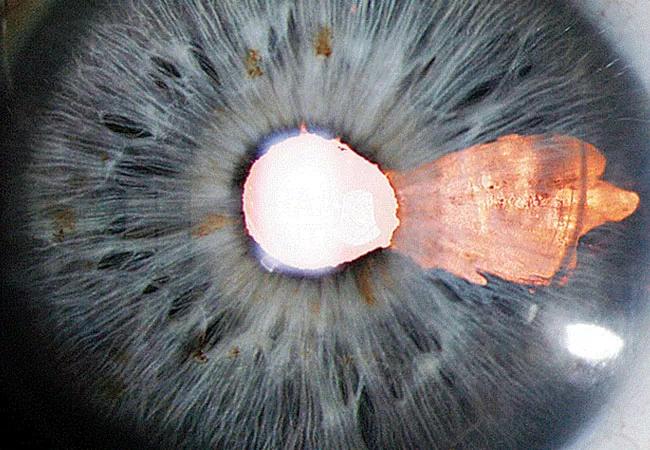

A 68-year-old woman presented for a second opinion on recurrent iritis in her left eye. She had been treated with prednisolone acetate. Over six months, the medication had increased her intraocular pressure, but every time she stopped using it the iritis would recur.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Her workup was negative for autoimmune disease, syphilis, tuberculosis and various other disorders. She did have a history of shingles and shingles vaccine.

An anterior chamber paracentesis detected varicella zoster virus (VZV). The patient was started on valacyclovir along with prednisolone acetate, which was tapered after two weeks. Her iritis resolved completely.

Uveitis — eye inflammation including iritis, retinitis and choroiditis — is generally thought to be caused by noninfectious conditions. Viral etiologies account for only about 10% of uveitis cases, estimates ophthalmologist Sumit Sharma, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute.

“It’s often overlooked,” he says. “In anterior uveitis, viral infections can become a longstanding problem. It doesn’t typically result in vision loss, but if it is wrongly treated as noninfectious — which it usually is — patients can be miserable with ongoing episodes. Posterior viral retinitis is different. If that infection is missed early on, it can quickly lead to permanent vision loss.”

Anterior and posterior viral uveitis present differently, making diagnosis challenging, notes ophthalmologist Sunil Srivastava, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute.

In anterior viral uveitis, signs and symptoms are typically unilateral and include:

Advertisement

In posterior viral uveitis, signs and symptoms include:

“More and more, we are seeing middle-aged patients who had a viral eye disease years ago now presenting with changes in their better-seeing eye,” says Dr. Srivastava. “If a patient has an atypical vasculitis or an atypical hemorrhagic presentation in their retina, consider viral disease.”

Another rising trend is uveitis caused by VZV, including virus acquired from live vaccine in immunocompromised patients.

“If you suspect viral uveitis, ask the patient if they’ve recently had shingles around the eye or received a shingles shot,” says Dr. Srivastava.

Definitively diagnosing viral uveitis requires anterior chamber paracentesis. Fluid from the eye is sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

But don’t wait for results to start treatment.

“Herpetic retinitis can be rapidly progressive,” says Dr. Srivastava. “It affects one eye first and then quickly affects the other. It’s important to treat it with systemic antivirals as soon as possible because once the disease affects the retina, vision loss can be irreversible.”

Posterior disease also can involve the optic nerve and spread to the brain, adds Dr. Sharma.

“To be safe, treat any areas of whitening in the retina as a viral infection until proven otherwise,” he says.

Treatment for viral uveitis, either anterior or posterior disease, requires antiviral medication. Intravitreal injection is first, especially if posterior disease is suspected, followed by 1-2 g of oral valacyclovir three times per day.

Advertisement

“If you don’t have access to intravitreal treatment, oral valacyclovir usually will release into the eye within a day,” says Dr. Srivastava. “The intravitreal injection buys some time if there’s a delay in insurance approval of the oral medication. Another option is admitting the patient for intravenous therapy.”

Additionally, topical or oral steroids can help resolve symptoms faster.

Viral retinitis almost always gets worse a few days — up to a week — after beginning treatment, notes Dr. Sharma. Having a definitive diagnosis through PCR testing is especially valuable at this time.

“The whitening of the retina will seem to spread,” he says. “But those areas of the retina were already infected by the virus. Whitening doesn’t occur until days after the virus infects the area.”

Continue the treatment, he says. Patients may need more than one intravitreal injection, typically on day 3 or 4 and on day 7. If they begin to improve, continue oral medication and watch them closely.

For recurring anterior disease, steroid and antiviral tablets should be continued for at least one year, sometimes longer, says Dr. Srivastava. For posterior disease, patients should continue 1 or 2 g of antiviral per day for life.

“Patients who have had a herpetic infection in the back of the eye have a high rate of recurrence without lifelong prophylaxis,” says Dr. Sharma. “Even with it, their lifetime risk will never be zero. Posterior viral disease comes with a high lifetime risk of central nervous system infection as well.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A review of pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment options

How computational tools and personalized biomechanics can improve keratoconus detection, ectasia risk assessment and surgical outcomes

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists