How a patient in the Southwest used our platforms to obtain surgical relief in Cleveland

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/36a76692-d18f-4664-8556-d4b177138999/Original-jpg)

Spine

Thanks to the expansion of virtual consults over the past several years, Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Spine Health is able to serve patients from all corners of the nation and beyond who otherwise wouldn’t be likely to be treated by the center, owing to distance. The case study below traces the path one such patient took through virtual evaluation for spine surgery to a January 2020 operation at Cleveland Clinic and continuing through virtual follow-up visits in recent months.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A middle-aged woman from the U.S. Southwest requested a virtual consultation with Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Spine Health in mid-2019 for persistent severe pain and dysfunction in her left leg. She had undergone multiple spine surgeries dating back to 2002, including an L5-S1 fusion (with subsequent revision) and an L4-5 fusion. Her current complaint of leg pain and dysfunction dated back to her most recent surgery, in April 2019, when she had a lateral spine fusion with cage placement at L3/4.

Several months after that surgery, the patient requested her virtual consult with Cleveland Clinic. This involved providing information about her case to Cleveland Clinic’s online triage system, including history, symptoms, and recent test results and imaging studies of her spine from her local providers. Data were supplied by the patient and her local providers and then abstracted by the Center for Spine Health’s triage office staff into the electronic health record (EHR). Images were uploaded via a secure web link with step-by-step instructions for the patient and her providers (alternately, images may be sent via CD-ROM).

These data laid the groundwork for the first of several virtual appointments, all conducted as MyChart® video visits using Zoom™ for Telehealth, a HIPAA-compliant service integrated with Cleveland Clinic’s EHR and MyChart online health management platform for patients.

The first visit was with a Center for Spine Health nurse practitioner in September 2019 and consisted of history-taking and an evaluation similar to that for any patient seeking assessment for potential spine surgery. Based on that visit, the patient was cleared for virtual consultation with a Center for Spine Health neurosurgeon, Michael Steinmetz, MD, in November.

Advertisement

“I had all the patient’s relevant imaging and objective data accessible at my first virtual visit with her,” says Dr. Steinmetz. “We were able to focus right away on whether or not we could offer a surgical solution to address her chronic pain and dysfunction.”

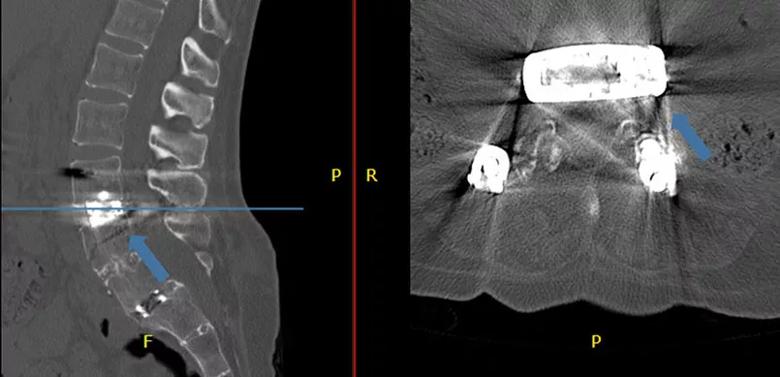

Those findings and his patient interview suggested she had a femoral neuropathy or L3 radiculopathy in the aftermath of her April 2019 operation. Review of her supplied imaging studies (Figure) revealed that nerves were tethered to the top of the implanted cage, which likely was largely responsible for her leg pain.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/09d8c980-ad17-4d3e-8f9d-09c1ea03a998/20-NEU-1918435_CQD-inset-805x389-1_jpg)

Figure. Sagittal and axial CT images of the lumbar spine supplied by the patient. The cage is placed posteriorly in the disc space. On the axial slice, it is apparent that the exiting nerve root is tethered over the edge of the cage (blue arrow).

The patient expressed her desire to have the cage removed, but Dr. Steinmetz advised that this posed too much risk. He took advantage of the Zoom platform to review the patient’s spine MRI and CT images with her, using arrow pointers to explain the risks and outline the surgical strategy he planned.

That plan involved a lateral extracavitary approach to the spine to remove screws that had been placed near the cage, remove virtually all the bone at the back of the spine around the cage, and then untether the nerve tissue from the cage.

The patient was amenable to the plan, so Dr. Steinmetz scheduled another virtual appointment in December to review the plan and confirm that the patient had realistic expectations. “It was important to reiterate that this was not a standard operation but rather an approach customized for her unique problem and that it wasn’t a magic bullet to address all the issues she was experiencing,” Dr. Steinmetz explains. “Again, the virtual consultation allowed us to discuss this, with her images at our disposal, after some time had passed in a way that wouldn’t be possible if she were a typical out-of-town patient.”

Advertisement

The patient came to Cleveland in January 2020 and was admitted to Cleveland Clinic’s main campus hospital the day of her scheduled surgery. After preoperative examination, she underwent the procedure as planned by Dr. Steinmetz and was discharged three days later, in late January.

“We were successful in removing the screws and the bone around the cage and also in untethering the nerves from the cage and elevating them,” says Dr. Steinmetz.

The patient returned to her home in the Southwest and had her first follow-up virtual visit with Dr. Steinmetz at the beginning of March. She was functioning significantly better — she could climb stairs again for the first time in many months — but still had some nerve pain for which she was continuing physical therapy with local providers. She reported a return of sensation in her thigh and was able to reduce the dosage of her pain medications. She estimated her pain to be reduced by 50% from her preoperative baseline and reported significantly improved quality of life.

At a subsequent follow-up virtual visit in July, she reported continuing physical therapy for her residual pain but expressed satisfaction with the improvement achieved since her surgery at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Steinmetz has recommended continuation of conservative therapy for symptoms with the possibility of eventual spinal cord stimulator therapy if her pain persists.

The follow-up virtual visits are conducted by Dr. Steinmetz with the patient’s local physician present as well, who works with him to perform the physical examination and supplement the patient’s reporting of symptoms and other developments.

Advertisement

Dr. Steinmetz and colleagues in the Center for Spine Health have been doing virtual evaluations of patients for spine surgery for more than two years, with the number of such consults swelling since the advent of COVID-19. He notes that the most remarkable aspect of these cases may be how similar they are to the cases of patients seen exclusively in person.

“Other than not having the ability to lay hands on the patient — which we do preoperatively if we jointly decide to proceed with surgery — there is not much difference in how I evaluate and manage patients virtually versus in person,” he says. “That is a testament to the systems and platforms we have refined over the past few years, which integrate the various steps of management fairly seamlessly for patients and providers alike. As a spine surgeon, I am able to have the patient’s relevant imaging, significant history, recent neurologic test results and similar information at my fingertips through the EHR. I can review imaging studies with the patient directly and use them to visually describe a potential operation. And I am still able to look patients in the eye via video and relate to them to address uncertainties and fears.”

The teamwork built into virtual evaluation and consultation yields efficiencies as well. “It’s key that virtual consultations begin with virtual appointments with our advanced practice providers to do screening and evaluation to supplement the data entered by our triage team to ensure we have all the information needed,” Dr. Steinmetz notes. “This allows me to focus my virtual visit with the patient on whether or not we can offer a surgical solution.”

Advertisement

In view of all the similarities with traditional in-person management, the biggest difference may be in the number and location of patients who benefit. “If we weren’t offering these services virtually, patients like this one may not get matched with the care they need,” he concludes.

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges