Designed for digitization, distance health, discovery and more

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5896d6b8-61c2-4c13-993e-eda89c7fe323/23-NEU-3627359-CQD-Hero-650x450-1_jpg)

23-NEU-3627359-CQD-Hero-650×450

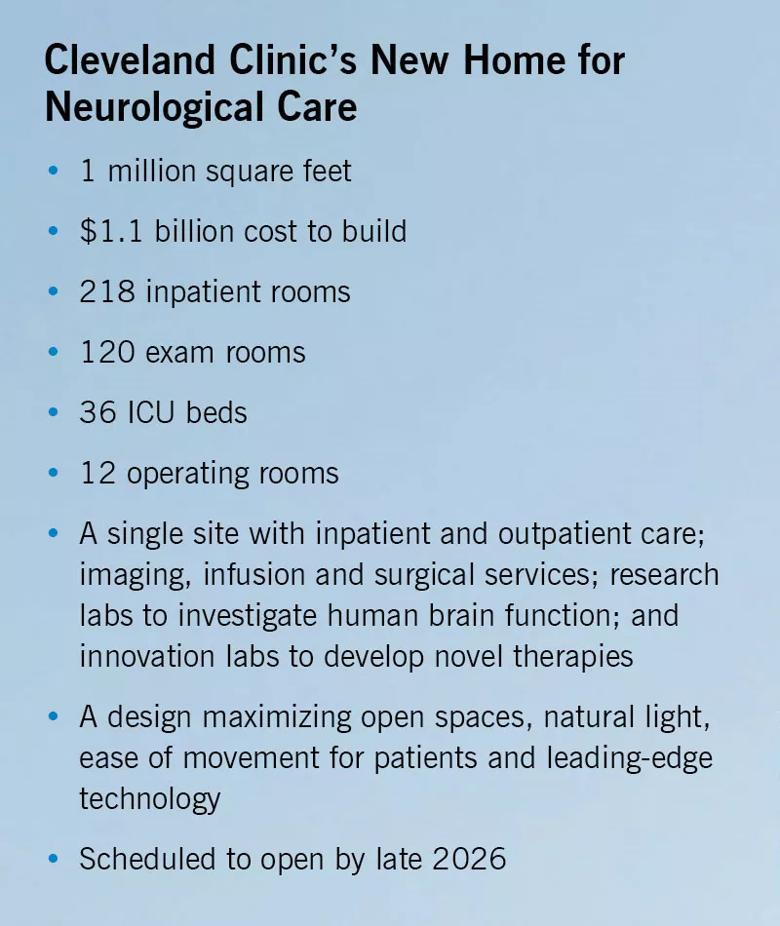

Cleveland Clinic is moving forward with construction of a new Neurological Institute building on the health system’s main campus in Cleveland. The 1 million-square-foot building (see artist’s rendering above) will dramatically expand the physical infrastructure dedicated to neurological care on the campus and consolidate inpatient and outpatient neurological care services under one roof (see figure). It also will include a number of unprecedented technological design features. Yet those won’t be the facility’s most salient aspects, according to Neurological Institute Chair Andre Machado, MD, PhD.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“What will be most notable about this building is not something structural but rather that it is wholly designed with people in mind — patients with neurological disease, their loved ones, and the clinicians and researchers caring for them,” Dr. Machado says. “Architecture is not about structures; it’s about people, and the building is designed for them. We want to provide our very talented team, and the additional talent we will recruit to this new facility, with the ideal spaces and technologies to deliver the best care possible today while simultaneously developing the neurological care of tomorrow. This facility will amass an enormous amount of concentrated knowledge, and we will put this critical mass to work toward new cures and the much-needed hope our patients and their loved ones seek.”

Consult QD recently asked Dr. Machado to flesh out the details of this vision for the building, which is scheduled to open by the end of 2026. The resulting conversation focused on six major aspects of the building’s design, as recapped below.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e24428d9-adfe-4d00-8bd5-3759f8632b2d/23-NEU-3627359-CQD-Inset-SideBar-800x950-v2_jpg)

Because of substantial disability among many patients with neurological conditions, the building design puts an extra premium on accessibility, Dr. Machado says. Open spaces will abound, and natural light will be maximized. Patient flows will be efficient and promote easy orientation. Wayfinding will be intuitive, with no mazelike corridors.

Beyond that, leading-edge technology will be ubiquitous, as detailed in some of the numbered items below. “We want patients to perceive the building as a place of cutting-edge capabilities where emerging solutions are offered and where they can participate in the development of treatments of the future,” Dr. Machado explains. “Most of the conditions we treat are currently incurable, so providing patients with hope and empowerment is important to the experiential side of the design as well.”

Advertisement

As Neurological Institute stakeholders began discussing the building design in earnest a few years ago, they recognized a need to overcome some inefficiencies of traditional care processes, such as manual data entry and patients’ need to repeat details of the reason for their visit to various members of their care team.

“We had an epiphany,” Dr. Machado explains. “We realized that as a patient walks through the building, most aspects of their neurological examination could be acquired as they interact with the building and our caregivers. After all, the neurological exam is largely an exam of performance measures such as speed, reflexes, balance, cognitive function and language. Many of these measures can be captured by sensors and similar tools as a patient navigates the building. These can be transferred to the electronic health record and paint a picture of the patient’s neurological condition before the formal visit begins. We will spend less time asking patients how they’re doing and spend more of our valuable time together discussing what we can do to make things better.”

The intent is for a high level of data acquisition in the building, and then to use the data to enhance care, including distance health. Dr. Machado notes that many of the necessary sensors and tools are becoming available, and Cleveland Clinic has a team of architects, engineers and IT experts working with clinicians to integrate them into the building design. Sensors in the building can be linked with patients’ performance measurements at home, captured via wearables and similar consumer technology. “As long as we evaluate the patient in the building every so often, we can co-register performance data obtained at home and validate those measures,” he says.

Advertisement

He emphasizes that participation in the building’s data acquisition capabilities will require patient consent, which will likely take the form of wearing a sensor that will allow data acquisition, so that data will not be captured for patients who don’t wish to participate (or for non-patients who move through the building).

This approach offers the advantage of assessing the function of patients who consent to participate at times when they don’t feel they’re being tested, so that the findings are not biased by a need to “perform” for an examiner. “The assessment will be more valuable, because patients will be acting naturally and we can capture any deficits along the way,” Dr. Machado observes. “This type of assessment has never been done before at scale.”

The building will be highly enabled to provide distance health, including digital connectivity with Cleveland Clinic sites across the nation and the world. These include the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas and Cleveland Clinic hospitals in Florida, London and Abu Dhabi.

“The new building will serve as a hub and connector of knowledge” Dr. Machado says. “Its large-scale digital health capabilities can extend the depth of expertise to provide more subspecialized care elsewhere and help others with decision-making.”

He cites the example of Cleveland Clinic’s Epilepsy Center, where staff in Cleveland currently monitor seizure activity in patients from around the globe on a 24/7 basis through sophisticated digital connectivity. “This allows for nonstop seizure monitoring in hospitals that wouldn’t otherwise have the capability for it,” he explains. “The new building will enable us to expand that monitoring further and offer similar distance health services at scale in additional subspecialty areas, providing expert care to as many people as possible.”

Advertisement

“A big part of the building will be dedicated not only to patient care but to human laboratories where we will test new diagnostics and treatments of the future,” Dr. Machado states. He’s referring to the planned Discovery Space where clinicians, scientists and engineers — from Cleveland Clinic and sometimes also from industry and other outside organizations — will collaborate to develop and test new interventions.

“This will be the interface between clinical care and research,” Dr. Machado continues. “Routine neurological care will increasingly be delivered outside of the main campus. This building is where patients can participate in care that is not yet routine, where we can try new approaches and iterate them to develop new treatments.”

The resulting care/research interface should be a significant draw for top clinicians and researchers, Dr. Machado believes. “This is where the future of neurological care will come from, and people will want to be part of that,” he says.

Much of the building will be modular in layout, with all spaces having a repetitive pattern based on standard ratios for patient rooms and outpatient offices. This will make it relatively easy to change the internal spaces based on changing needs or new technologies. “This flexibility will allow us to get the most out of a very big investment,” Dr. Machado explains.

The design also sidesteps the competition between clinical and administrative space by embedding within some exam rooms a partially shielded “nook” that can serve as a small office space for physicians. Outside of patient hours, a physician can open up the nook and have a larger office space if they wish. “The idea came from study nooks in old European buildings,” Dr. Machado notes. “It uses space more efficiently by avoiding the down time when either the physician’s office or the clinic space sits idle.”

Advertisement

Neurological Institute clinicians — physicians, nurses, physical therapists and others — have been involved in every step of the building’s design. They’ve provided detailed feedback on various iterations of a mock facility with actual-size replicas of proposed room types filled with cardboard furniture and equipment.

“Our nurses have been particularly instrumental in giving us reality checks on what will be ideal for patients in terms of balancing privacy [every inpatient room will be private] with safety and supervision,” Dr. Machado says. A key example is the plan to position nursing stations between small windows that provide angled views inside two patient rooms at once to allow patient monitoring at any time.

What excites Dr. Machado most about his institute’s soon-to-be new home? “We are charged with a dual mission,” he says. “We must do everything we can with what we have today for the patients in front of us now while also developing the neurological care of tomorrow. I believe this building and the talent that will inhabit it will enable discovery of the neurological care of the future. That’s what excites me most.”

Advertisement

A principal investigator of the landmark longitudinal study shares interesting observations to date

Preclinical work promises large-scale data with minimal bias to inform development of clinical tests

Research aims to extend observations of reversal learning in mice to human neurological disorders

Multicenter collaboration aims to facilitate tracking of neurological activity deep within tissue

Making a difference by putting empathy into action

Structured interventions enhance sleep, safety and caregiver resiliency in high-acuity units

An unexpected health scare provides a potent reminder of what patients need most from their caregivers

Automating routine medical coding tasks removes unnecessary barriers