Physicians present a case study, discuss clinical guidelines and the value of a multidisciplinary approach

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d513d3e5-8fc1-4e99-a73e-776d913dca8f/650x450-vape-CT-chest-coronal_jpg)

650×450-vape-CT-chest-coronal

By Humberto Choi, MD, Maeve MacMurdo, MBChB and Valeria Arrossi, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 57-year-old Caucasian male presented with a week-long history of nonproductive cough, fever and malaise. The patient had no significant past medical history and had been in good health.

His fevers reached as high as 39.5 C (103.1 F), were cyclical in nature and accompanied by drenching night sweats. Though he did not have dyspnea, on initial assessment he was hypoxic with oxygen saturation of 85% while breathing ambient air. His physical examination was also significant for a respiratory rate of 30 to 35 breaths per minute, heart rate of 110 to 125 beats per minute and temperature of 38.7 C (101.66 F). Cardiac and pulmonary examination was unremarkable, without audible crackles or wheezing. The patient had no skin rash or joint swelling.

He denied any recent travel or relevant occupational exposures, and stopped smoking tobacco almost 20 years previously. However, he endorsed daily marijuana use. He stated that while he smoked “blunts” for 20 years, over the past year he switched to vaping with electronic cigarettes containing tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which he reported using three to four times daily for the past 12 months.

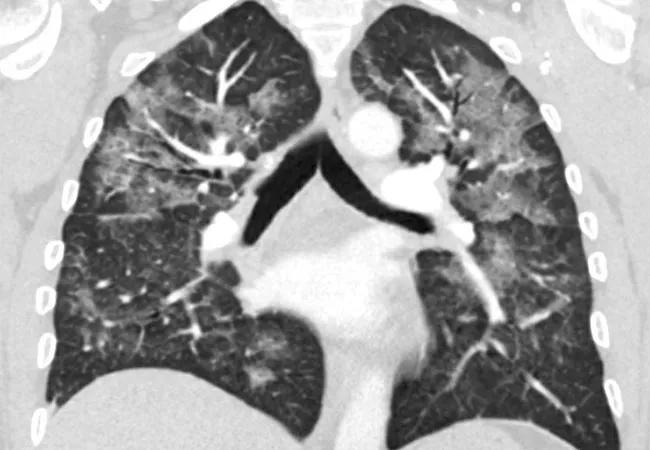

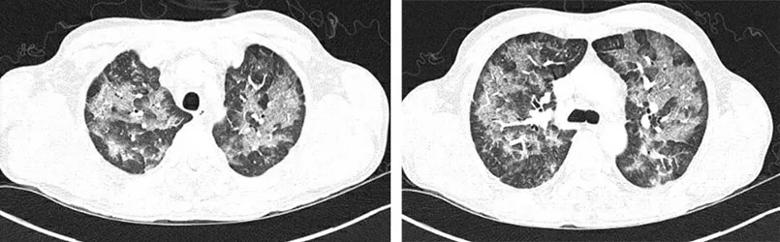

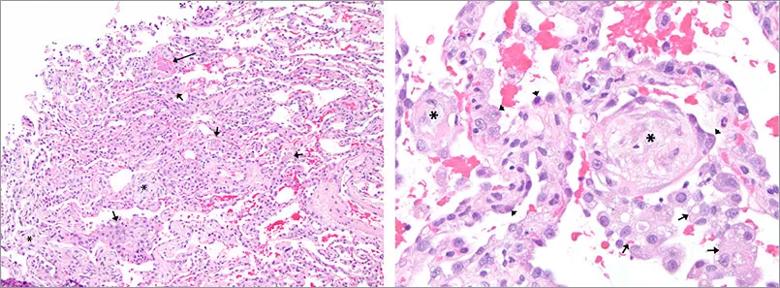

A CT chest was obtained, revealing diffuse patchy, nodular and confluent ground glass opacities with interlobular and intralobular septal thickening and dependent basilar atelectasis (Figure 1A, B). Stains and culture of sputum were negative for infectious etiologies. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage showed macrophage predominant lavage fluid, and transbronchial biopsy revealed focal organizing pneumonia (Figure 2A, B).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/da170a1f-dcd2-465b-8b64-ef733a83abf3/805x-Inset-1_jpg)

Figure 1A-B

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/aecfd8be-bea2-4eca-8165-090c38887626/805x-Inset-2_jpg)

Figure 2A-B: Microphotographs of the transbronchial biopsy showing focal organizing fibrin (long arrow), alveolar fibromyxoid plugs (*), reactive type II pneumocytes (arrow heads) and airspace histiocytes (short arrows).

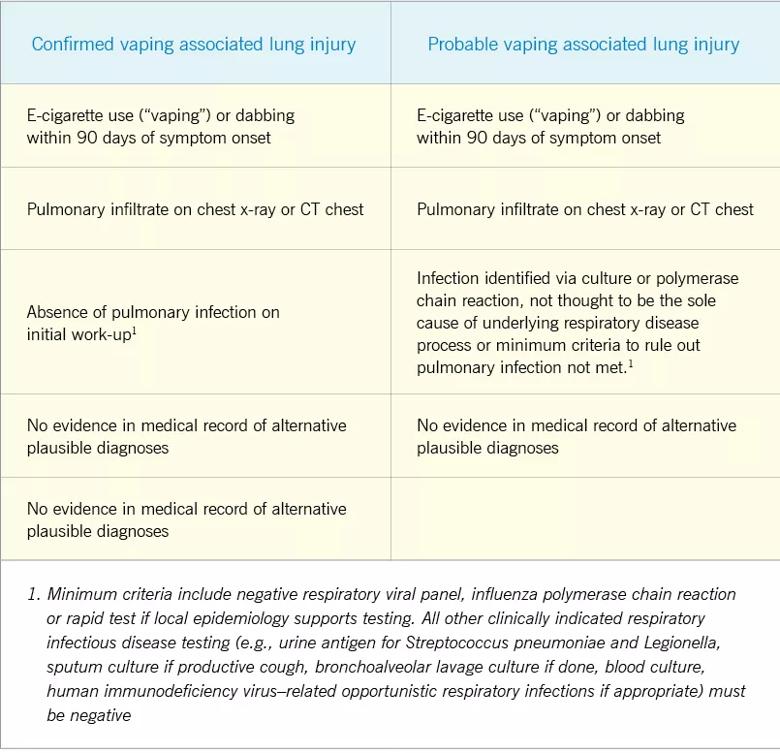

Using the Centers for Disease Control case definition, a diagnosis of vaping-associated lung injury was made (Table 1).1 With expectant management and avoidance of further vaping the patient’s symptoms improved rapidly, with full resolution of his hypoxia by day three after presentation. He was discharged home with referrals for substance dependence treatment and outpatient pulmonary follow-up.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0e884161-8c83-49f9-a17a-2c2e51028f8c/805x-Inset-Chart-Vaping_jpg)

Table 1: CDC case definitions of confirmed and probable vaping-associated lung injury

This report illustrates a case of a patient with vaping-associated lung injury. Since June 2019, more than 1,000 cases of vaping-associated lung injury have been reported.2 The reason for the sudden onset of this new epidemic remains poorly understood, though increasing evidence suggests that the syndrome may be related to use of vaporizer cartridges modified with THC or other additives.

In patients for whom vaping-associated lung injury is suspected, a full vaping history should be obtained, including substances vaped, type of vaporizer used and the source of cartridges. A large number of identified cases report obtaining their vape fluid either from friends, family or from black market dealers, which has contributed to the difficulties in identifying a single cause of the outbreak.2

Advertisement

Initial symptoms may be nonspecific, including fever, malaise, abdominal pain and diarrhea.3 The majority of patients will also develop respiratory symptoms, though these may not present until later in the disease course. The spectrum of severity is variable, ranging from mild symptoms to acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. To date, 18 deaths due to vaping-associated lung injury have been documented, likely an underestimate of the true burden of disease, since recognition may be difficult and there has not been a standard for reporting the diagnosis to public health agencies.

Evaluation of suspected vaping-associated lung injury should include complete blood count with differential, toxicology screening and chest imaging early in the disease course. Testing for infectious etiologies should be performed in keeping with initial clinical presentation. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsies may be considered in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or where infection is not fully excluded.

The lung histopathology in our case demonstrated organizing pneumonia. The main histopathologic findings that have been described in association with vaping-associated lung injury, are those of organizing acute lung injury, including organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, acute fibrinous pneumonitis and eosinophilic pneumonia.4 Foamy macrophages, were described in a subset of cases, however, features of exogenous lipoid pneumonia have not been documented.5 Peribronchial inflammation, and rarely, features similar to hypersensitivity pneumonitis, have also been reported

Advertisement

Many patients with mild disease will improve with cessation of vaping alone. For those whose symptoms are severe, or who have significant hypoxia, treatment with systemic corticosteroids may be considered. The appropriate dose and duration of treatment with corticosteroids are still unclear.

Working as a multidisciplinary team, the Cleveland Clinic Respiratory Institute has developed an internal guideline for early recognition and management of patients with vaping-associated lung injury. Early input from a radiologist and a pathologist is recommended in cases where vaping-associated lung injury is suspected, given the variety of imaging findings and pathologic patterns identified to date.

It is important to note that many of these patients, in addition to their severe acute lung disease, may also experience addiction to nicotine or to other substances, placing them at increased risk of vaping-relapse. Early referral to addiction treatment is strongly recommended. The Cleveland Clinic Smoking Cessation Program offers resources and support for patients interested in overcoming vaping-related nicotine dependence. For those patients interested in accessing these services, further information can be found at http://www.clevelandclinic.org/stopsmoking.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Takeaways from the most recent annual meeting centered around clinical advances, AI integration and professional development

Recent breakthroughs have brought attention to a previously overlooked condition

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Looking at the real-world impact and the future pipeline of targeted therapies

The progressive training program aims to help clinicians improve patient care

New breakthroughs are shaping the future of COPD management and offering hope for challenging cases

Exploring the impact of chronic cough from daily life to innovative medical solutions

How Cleveland Clinic transformed a single ultrasound machine into a cutting-edge, hospital-wide POCUS program