New findings presented at ACS Clinical Congress 2017

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/82bece4b-1fee-453c-8431-c66bafb12cf2/17-DDI-4596-Bariatric-Heart_jpg)

17-DDI-4596-Bariatric-Heart

While the World Health Organization has referred to obesity as an under-recognized, global epidemic since 2000, excess weight continues to be a leading cause of disease, debilitation and death around the world.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Commonly discussed conditions caused or exacerbated by BMI include type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, liver dysfunction, respiratory and musculoskeletal disorders, psychosocial problems and certain types of cancer. Various forms of bariatric surgery have proven to suppress hunger and reverse or slow progression of many of these conditions.

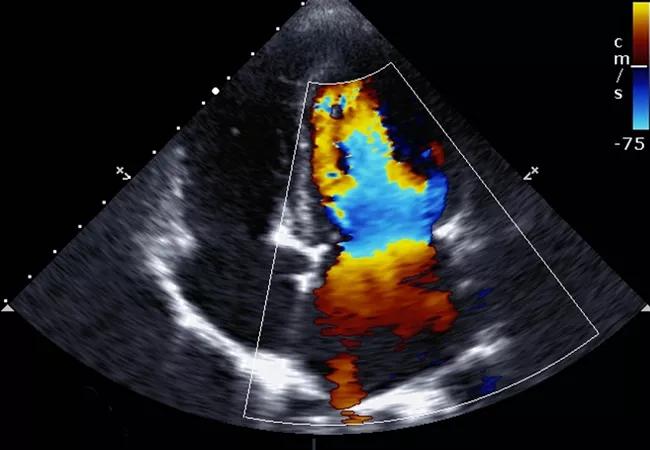

What’s less widely understood is that obesity affects the heart’s geometry, according to Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, General Surgery Chairman and Director of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

New research presented by Dr. Rosenthal at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2017 suggests a bariatric surgical procedure and the weight loss that follows it can reestablish the heart to its natural shape and function.

When confronted with fat, the heart has to pump harder to move blood through the body, which causes the heart to grow bigger. Unlike other muscles in the body, the larger the heart muscle, the less effectively it performs.

“We’ve known for some time that the cardiovascular system is significantly affected by this disease process,” says Dr. Rosenthal, the lead author of the study. “What we didn’t know was the degree to which the heart structure changes in someone who loses weight after having bariatric surgery.”

Dr. Rosenthal and his co-investigators, Rajmohan Rammohan MD, Nisha Dhanabalsamy MD, Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, and Samuel Szomstein, MD, also examined how this change in geometry affects ventricular function.

Advertisement

The research team retrospectively reviewed data from 51 bariatric surgeries between 2010 and 2015, where patients had had echocardiography before and after the surgery. The analysis included factors such as BMI and coexisting health problems. The average age of the patients was 61 and the average BMI was 40. Sixty percent (31) were female.

After one year, 25 patients (49%) showed normal left ventricular geometry. Specifically, the left atrial mass (229 ± 82.1 vs. 193.2 ± 42.5, P < 0.01, 95% CI) and the left ventricular end diastolic volume (129.4 ± 53 vs. 96.4 ± 36.5, P = 0.01, 95% CI) showed significant modification following the procedure. There was also significant modification in the interventricular septal thickness (P = 0.01, 95% CI) and relative wall thickness (< 0.01, 95% CI) following surgery.

“We were encouraged to see the heart return to its normal geometry after bariatric surgery and weight loss,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “There is a direct positive correlation between the decrease in BMI and the improvement of the left ventricular structure.”

Further studies will be conducted to define the damage of obesity to the diastolic function and to determine how the amount and timing of weight gain and weight loss may affect outcomes.

“We don’t know, for example, if the heart always will come back to normal, regardless of how long a patient was living with obesity,” explains Dr. Rosenthal. “It may be if you wait too long, the changes in your heart are irreversible.” The team will look at patient follow-up at intervals beyond one year.

Advertisement

The research findings further support the need for doctors to be more proactive with patients presenting with obesity. The medical community is obliged to help the patient overcome fear and financial barriers, says Dr. Rosenthal.

“We have to continually ask ourselves what we can do to help patients live longer and live better,” he says. “Re-establishing heart size has enormous implications for the whole body. But we believe it is critical to intervene early.”

Dr. Rosenthal and his Cleveland Clinic colleagues have conducted an abundance of research that supports weight loss surgery for patients overweight by more than 100 pounds or for patients with a BMI between 35 and 39.9 with an accompanying obesity related health condition.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Pheochromocytoma case underscores the value in considering atypical presentations

Advocacy group underscores need for multidisciplinary expertise

A reconcilable divorce

A review of the latest evidence about purported side effects

High-volume surgery center can make a difference

Advancements in equipment and technology drive the use of HCL therapy for pregnant women with T1D

Patients spent less time in the hospital and no tumors were missed

A new study shows that an AI-enabled bundled system of sensors and coaching reduced A1C with fewer medications