Pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment and a COVID-19 connection

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

No laboratory test can identify it, no biopsy can confirm it, but myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) remains one of the most common musculoskeletal afflictions a person can experience. MPS is a chronic condition that causes everything from vague discomfort to severe pain in people of all ages. It is a leading cause of disability in those who are between 20 and 64, and it occurs in about 85% of people sometime during their lifetime.

Familiarity, however, does not always lead to clarity. MPS is often underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed. More than a century after it was first identified, its pathogenesis is still not well explained. Still, a better understanding of diagnostics and treatment options can help ensure that MPS patients receive the most appropriate care and have the highest likelihood of regaining function.

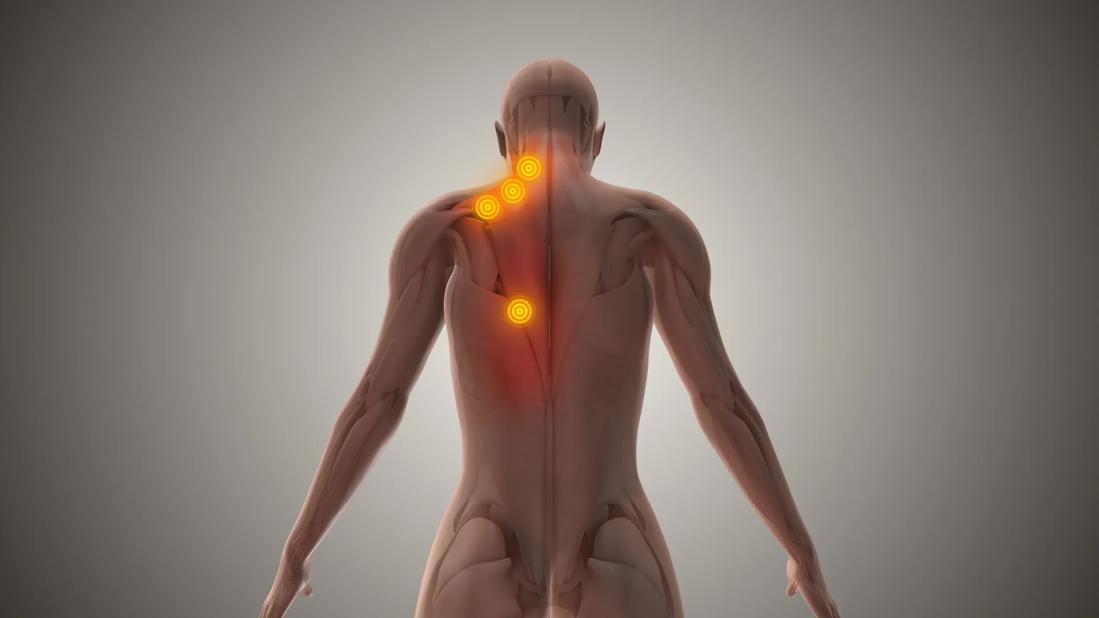

Defining characteristics of MPS are the presence of specific trigger points occurring within a muscle unit sarcomere, which typically develop in the trapezius, craniomandibular region, pelvic and lumbar regions, and limbs. Compression of trigger points elicits pain; a distinct central nodule can be detected during palpation. Risk factors include muscle trauma, postural tension and skeletal asymmetry, musculoskeletal disease and metabolic disorders. Hypothyroidism and iron or vitamin D deficiencies also can be risk factors.

While the contraction of sarcomeres within the skeletal muscles causes the trigger points, the mechanism remains unclear. Hypotheses that may offer paths to understanding include:

Advertisement

Likewise, cellular changes offer some mechanistic clues. Those include increased levels of IL-1b, IL6, IL8, TNF, bradykinin, calcitonin-related peptide and norepinephrine, fewer mitochondria; and dysregulation of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK).

Even without a fuller understanding of the mechanism of MPS, careful and discerning clinical assessment can make the difference in diagnosis and treatment. Criteria for diagnosis has shifted over the decades, with Janet Travell, MD, and David Simons, MD, proposing a five-point system in 1999, and Elizabeth Tough publishing a 19-item list in 2007.

Then in 2017, a group of 60 experts from 12 countries identified three criteria that are widely used today. Two must be met for positive diagnosis:

Among the most notable challenges of diagnosis are similarities between MPS and fibromyalgia. Differentiating between a fibromyalgia tender point and a myofascial trigger point is challenging because we lack agreement on the essential criteria for myofascial trigger point diagnosis. Detection of the taut band can be unreliable. In addition, “tender spot and recognizable pain stimulation,” a key criterion, overlaps with features of fibromyalgia.

MPS also can become widespread, mimicking the appearance of fibromyalgia. Differences in certain characteristics can be helpful, however. While the etiology of fibromyalgia is unknown, MPS is triggered by injury from gross or repetitive micro-traumas. Location of fibromyalgia tender points are expressed bilaterally and systemically, while MPS trigger points emanate at the juncture of motor neurons and skeletal muscle. Patients with MPS may show sign of weakness without atrophy and reduced range of motion. Distinctive local twitch response can be detected.

Advertisement

Because no single treatment approach is efficacious for all patients, managing MPS is difficult. An integrated, multi-faceted approach geared toward releasing the trigger points holds the most promise. Common pharmacological interventions include NSAIDs, muscle relaxers, membrane stabilizers and antidepressants. Injected Botox® A (BTX-A) injections can offer extended muscle relaxation by inhibiting acetylcholine release from the terminal end of the motor nerve axon. Studies have indicated that combining BTX-A with physical therapy also may be helpful.

Injections of anesthetics – a lidocaine and bupivacaine are common – into the trigger point may achieve local vasodilation, tissue relaxation and lengthening, and the removal of nociceptive substrates. The pain cycle may be broken from a single injection, but repeated treatment may be necessary. In one study, myofascial trigger point needling (dry needling) was found to be as effective as lidocaine injection.

Dry needling, along with acupuncture, are among useful nonpharmacologic treatment modes. Others include:

Advertisement

While there is still much to learn about COVID-19, a small study of patients receiving care at a pain clinic between March and December of 2020 indicated that some may have developed MPS as a result of having been infected with SARSCoV-2. Chart reviews indicated that the three patients who had had COVID-19 experienced worsening pain in specific focal points after infection. Once MPS treatment was begun, the patients reported improvement by at least 25%.

Possible mechanisms for SARS-CoV-2-induced MPS include muscle dysfunction caused by hypoxia, psychological stress and trauma, and changes in physical activity while they were infected. Further research is needed.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How chiropractors can reduce unnecessary imaging, lower costs and ease the burden on primary care clinicians

Compassion, communication and critical thinking are key

Add AI to the list of tools expected to advance care for pain patients

Cleveland Clinic study investigated standard regimen

Despite the condition’s debilitating, electric shock-like pain, treatment options are better than ever

Program participation correlates with reduced use of opioids, X-rays and ED visits

Tapping into motivational interviewing to guide behavioral change

Relieves discomfort, reduces opioid dependency and improves quality of life