A review of takeaways from the recent U.K. national guidelines

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a705d6dd-62d2-4792-8fac-e0bc594d368e/23-NEU-4186662-trigeminal-nerve-650x450-1_jpg)

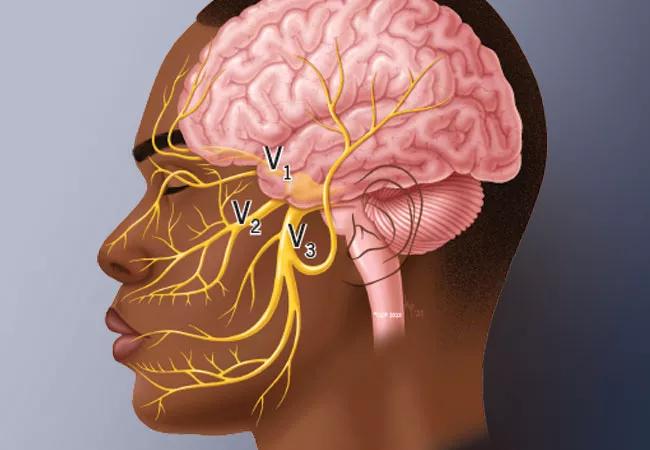

illustration showing the three branches of the trigeminal nerve

By Mun Seng Chong, MBBS, MD, FRCP; Anish Bahra, MBChB, MD, FRCP; Joanna M. Zakrzewska, BDS, MB BChir, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This article is reprinted from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2023;90[6]:355-362). Its discussion is focused on recent national guidelines for trigeminal neuralgia issued in the United Kingdom.

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a condition causing severe, unilateral, episodic facial pain. The diagnosis of TN is clinical, and patients typically report brief, lancinating attacks triggered by eating, drinking, talking, touching the face or even a puff of wind. There is a distinction between typical TN paroxysms, where there is no pain between episodic attacks, and TN with concomitant pain, where there is background pain between attacks.

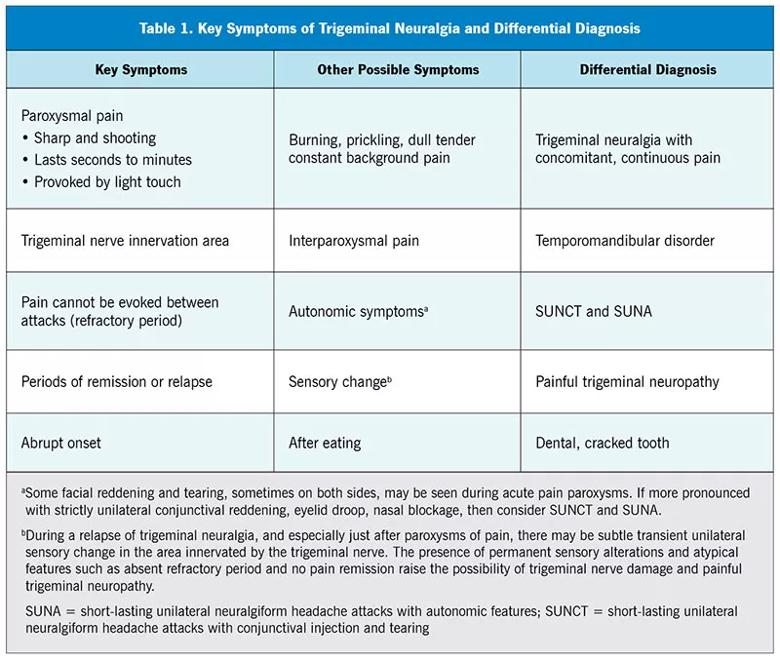

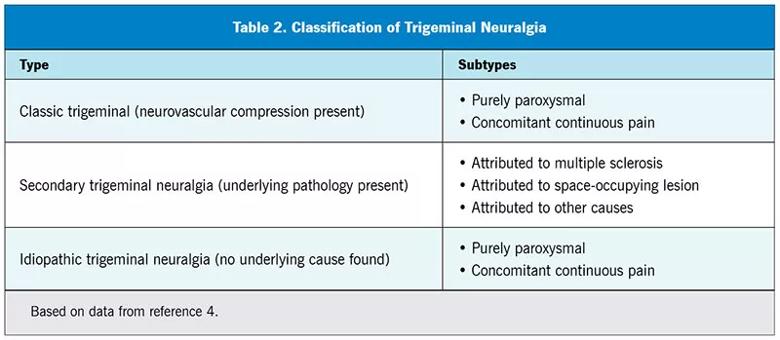

Key symptoms and the differential diagnosis for TN are summarized in Table 1. The lifetime prevalence of TN is estimated to be 0.3% (95% CI, 0.1%-0.5%),1 but this has not been validated, and it may be more frequent. TN is more common in persons ages 50 to 60, with a slight predominance in women.2,3 There are three etiologic classifications for TN4:

Secondary TN, due to multiple sclerosis or tumors (mostly benign), can present in a very similar way to classic TN, and these patients can also have periods of remission. It is important to evaluate whether there are any auditory symptoms or signs, as these may indicate a tumor, which will require a different management approach. TN can be the primary diagnostic factor in 7% of patients with multiple sclerosis.5

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0f576271-93d3-49a3-8b7c-520fce1b075d/23-NEU-4186662-CQD-Inset-Table1-v2-800x677-1_jpg)

Although symptoms of TN may stop spontaneously, the pain is severe and distressing. It was reported that patients with TN experienced a threefold higher risk of anxiety and depression compared with a control group.6 Another study estimated that 45% of patients with TN (89 of 198) reported more than 15 days of interference in daily activity in the prior six months, 35.7% (75 of 210) had mild to severe depression and half had anxiety symptoms.7 The fear of an attack was reported to lead 30% of patients with TN (30 of 103) to experience symptoms consistent with posttraumatic stress disorder.8

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0226c1a2-934e-47da-9980-3999126dea7a/23-NEU-4186662-CQD-Inset-Table2-800x349-1_jpg)

The care pathways for patients with TN are extremely variable, partly due to the wide range of specialists consulted. There is therefore a need to establish evidence-based care plans for the management of both acute and chronic TN, using a multidisciplinary approach endorsed by all stakeholders. It is with this in mind that the Royal College of Surgeons of England issued TN national guidelines for the United Kingdom (U.K.).9 These were based on the recently published European Academy of Neurology guidelines.10 The discussion of guidelines here refers to the U.K. guidelines unless otherwise noted.

These guidelines apply to all patients with TN as outpatients or inpatients in both primary care and secondary care settings.

The intended audience is primary care, medical and dental practitioners as well as all specialists who manage patients with TN. Appendix A of the guidelines provides a plain-language summary for patients with TN to inform them of the current care recommendations and help them make informed choices.

Advertisement

The guidelines were written by a multidisciplinary team representing the following organizations:

The guidelines were prepared under the auspices of the Faculty of Dental Surgery of the Royal College of Surgeons England using their guideline development process encompassing literature search, peer review, public engagement and approval by the Faculty. The guidelines are available on the Royal College of Surgeons of England website, with the expectation that there will be timely review and updates.9

The guidelines recommend the diagnosis and phenotyping of TN by multidisciplinary teams, especially the early contribution from a qualified dental specialist to exclude local intraoral causes of pain.

Approach to diagnosis

The diagnosis of TN is noted to be complex and should also include the measurement of patient-related outcomes such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Penn Facial Pain Scale−Revised, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. In primary care, documenting the intensity and frequency of symptoms and the impact on quality of life using a rating of mild, moderate, or severe could provide useful data on treatment outcomes after the use of medications. Patients should be provided with written information such as the Brain and Spine Foundation Facial Pain Booklet.

Advertisement

Use of MRI to investigate the underlying cause of TN is advocated; if MRI is contraindicated, use brain CT and angiography and neurophysiologic tests such as brainstem auditory evoked potentials. Our standard request is for thin-slice MRI of the brain and internal auditory meatus, and enhancement is not usually required. The images should be reported by experienced neuroradiologists and reviewed with the treating clinicians. High-quality thin-slice MRI provides high sensitivity (88%; 95% CI, 80%-93%) and specificity (94%; 95% CI, 91%-96%) of potential nerve compression or distortion.10

Drug therapy

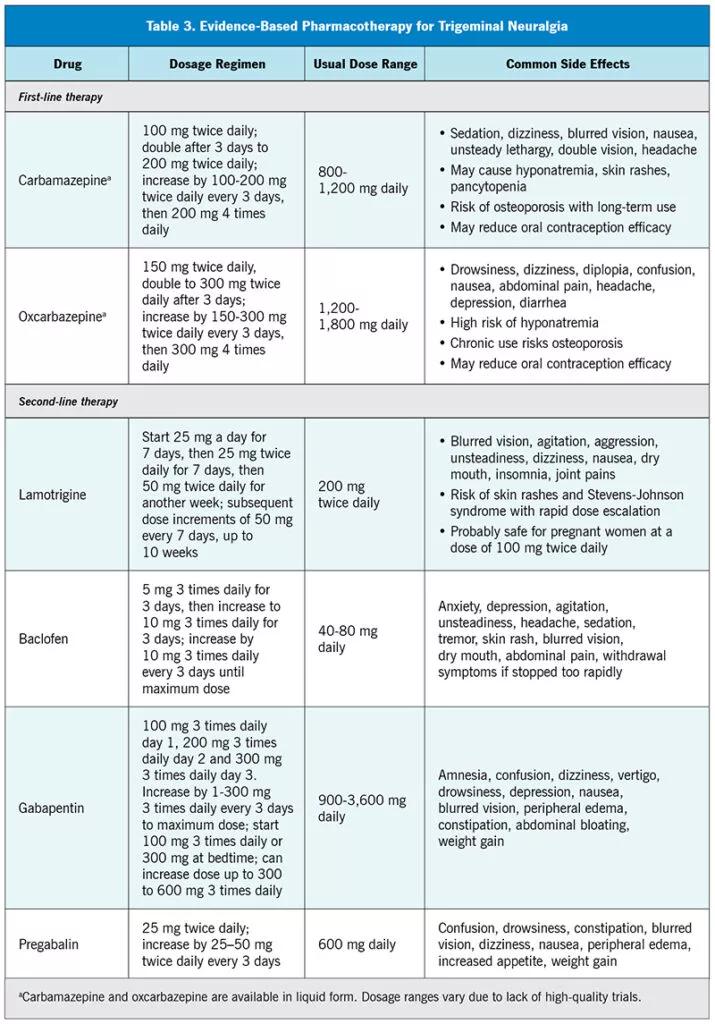

The guidelines summarize the data for recommending pharmacotherapy; the best evidence is for carbamazepine, but the use of oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, baclofen, gabapentin and botulinum toxin is also addressed. The recommendation for primary care physicians to start patients with TN on first-line medication before referral to a specialist is pragmatic and avoids treatment delays. First-line and second-line medications, dosage and side effects are outlined in Table 3. Individuals of Han Chinese or Thai origin are at risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome when using carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine.10

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8666281b-90f9-4cda-9007-2bd8550ec53a/23-NEU-4186662-CQD-Inset-Table3-v2-800x1145-1-715x1024_jpg)

In practice, individualized pharmacotherapy plans are needed, balancing the benefits and side effects experienced by each patient. Because TN is a paroxysmal disorder, it is difficult to judge when to reduce and withdraw treatment. Many patients choose to continue medications even when in remission. Careful guidance and counseling may be needed to help patients de-escalate and withdraw from treatment. These drugs are generally safe, and some primary care physicians may have previously prescribed them for treating epilepsy or other neuropathic pain conditions. Rapid pain control should be the main aim, and there is no reason why primary care physicians cannot initiate second-line therapy depending on their knowledge and experience. Some patients with TN may be adequately managed outside specialist centers, though these guidelines provide a framework for multidisciplinary care.

Advertisement

Management of acute relapses

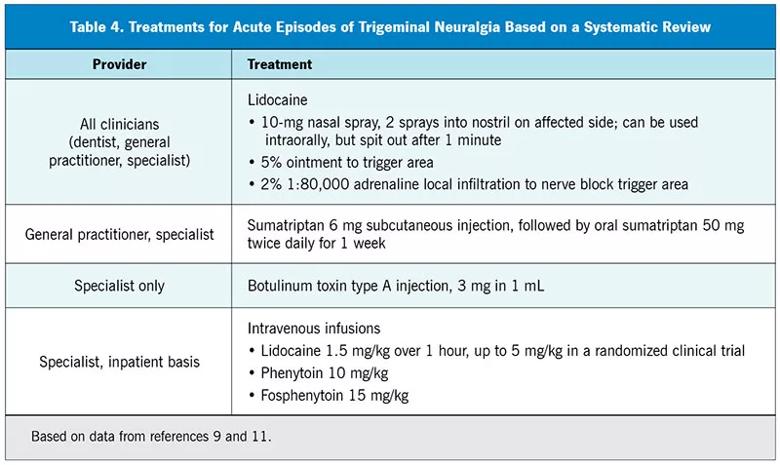

Although few papers in the medical literature address managing acute TN relapses, the guidelines summarize the current literature. The experts advised that lidocaine can be administered in three different ways to manage TN: nasal spray, local nerve block and intravenous infusion. There is some evidence for the use of botulinum toxin, as well as a recommendation for a trial of subcutaneous sumatriptan to alleviate an acute TN attack. Intravenous lidocaine, phenytoin and fosphenytoin are also suggested for inpatient treatment (Table 4).9,11

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4e8990e1-6a00-446e-82f0-67acfe0ac0e6/23-NEU-4186662-CQD-Inset-Table4-800x477-1_jpg)

Neurosurgical management

The guidelines recommend involvement of neurosurgeons who are experienced in managing TN when pharmacotherapy is ineffective or causes intrusive side effects. To better support informed decision-making, a neurosurgical consult is best done when a patient’s pain is in remission. Patients should be aware that invasive procedures are only expected to reduce brief lancinating pain and that they have unpredictable effects on the interparoxysmal pain, or can even make it worse. The guidelines state that 25% to 40% of patients with TN choose surgery within two years of symptom onset.9

Surgical treatments for TN include posterior fossa microvascular decompression (MVD) and neuroablative therapies such as stereotactic radiosurgery, radiofrequency thermocoagulation, balloon compression, glycerol rhizolysis and internal neurolysis. For patients with classic TN (i.e., arterial contact on the trigeminal nerve), MVD has the best surgical results for medication-free, long-term pain relief, with 62% to 89% of 5,149 patients reportedly pain-free at follow-up of 3 to 10.9 years.9,10

In posterior fossa MVD, any vessels or arachnoid tissue compressing the trigeminal nerve in the root entry zone is moved away. If no compressions are found, internal neurolysis may be performed to separate (or “comb”) the fascicles of the trigeminal nerve. Patients need to be medically fit to undergo MVD, and there is a 0.3% mortality rate and a risk of complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leak, infection and stroke, but a lower risk of sensory changes.10

Neuroablative therapies (i.e., stereotactic radiosurgery, radiofrequency rhizotomy, balloon compression, glycerol rhizolysis) involve controlled damage to the trigeminal nerve and have a lower mortality risk but are more likely than MVD to increase the chance of altered sensation, including the loss of corneal reflex.10 Neuroablative treatments have varying levels of success, with an average of two to four years.10

Stereotactic radiosurgery, compared with all other procedures, may have the lowest risk of short-term complications, but it has an increased probability of causing facial numbness and dysesthesia,10 as well as a long postprocedure duration before expected pain relief or complications. Glycerol rhizolysis (denervation using a chemical) offers the lowest chance for both,10 while radiofrequency thermocoagulation (denervation using heat) is reported to have a higher chance of success but also a greater risk of sensory loss than with all other procedures.10

Efficacy of surgical procedures

The guidelines include the efficacy of surgical procedures for TN as reported by Bendtsen and colleagues,10 but it is important to emphasize that the results are from single-intervention, nonrandomized studies among select patients in specialized centers.10 Individual patients may not achieve the same level or duration of pain relief. Patients with interparoxysmal pain need to be cautioned before choosing neuroablative treatments such as glycerol rhizolysis, balloon compression and radiofrequency rhizotomy. Pain between lancinating exacerbations may indicate existing nerve damage, and further iatrogenic destruction may lead to anesthesia dolorosa (a feeling of pain in an area that is completely numb to the touch).

Timing and selection of surgical treatment

The guidelines are not prescriptive about when or which surgical operation should be offered, and any such decision must be made jointly between well-informed patients and their clinicians from multiple disciplines. Neuroablative procedures for TN may require an overnight hospital stay and can be performed in patients who have other comorbidities. Surgical complications should be balanced against the side effects of long-term pharmacotherapy.

Referral for pain management

The guidelines recommend patient referral to pain management programs with access to clinical psychologists and physiotherapists because the pain severity, disruption of daily life and associated psychological impact of TN can adversely affect a patient’s mental health. The fear of a relapse cannot be underestimated. Pain psychologists and pain management nurse specialists can help patients alleviate some of these fears. Patients should be encouraged to join a TN support group such as Trigeminal Neuralgia Association UK (www.tna.org.uk), which has a multidisciplinary clinician panel offering advice.

Need for long-term follow-up and outcomes evaluation

A key recommendation of the guidelines is to urge clinicians managing patients with TN to follow up and gather long-term patient outcomes data to evaluate treatment efficacy and results. TN is a relapsing-remitting condition, and initial pain improvement may not always be due to treatment. This is especially true for invasive procedures, where initial good response may be followed by treatment complications and relapses.

Previous guidelines have been developed solely by experts in the field, whereas for the U.K. guidelines, all potential caregivers were consulted. A patient representative from the Trigeminal Neuralgia Support Group was included, as well as representatives from the Brain and Spine Foundation, a charity specializing in producing booklets for the general public on neurologic conditions. The new guidelines also recommend aids such as the Ottawa Personal Decision Guide to help patients make informed choices.

Pharmacotherapy and surgical treatments are recommended according to the best available evidence, as with other published guidelines.10 The U.K. guidelines include use of botulinum toxin injections and emphasize early discussion of neurosurgical options to inform patients of the full array of possible treatments. There is also strong emphasis on the need for TN care to be delivered by a multidisciplinary team.

The guidelines encourage primary care physicians to promptly diagnose TN and initiate pharmacotherapy after ruling out dental causes of facial pain. All patients should be evaluated to rule out secondary causes of facial pain, even if the pain is in remission. If relapses occur, referral to a multidisciplinary specialist team is advised to inform patients about the most appropriate treatment for their condition.

The coalescence of interested clinicians can prompt the collection and evaluation of long-term outcomes data to improve TN care. One example was an audit of 129 patients with TN evaluating treatment efficacy by choosing outcome measures meaningful to patients.12 Using the Patient Global Impression of Change score, 79% of patients (102 of 129) reported their condition was better since starting treatment in a specialist center. Notably, even in this study in a multidisciplinary specialist center, 20% of patients did not experience improvement in their condition,12 a finding that should prompt further research to bridge this management gap.

The data also revealed that the long period of inadequate pain control between symptom onset and specialist referral contributes to patients’ perception of treatment failure. A review of outcomes over an 11-year period in 285 patients without prior surgery for TN reported that 54% (153 of 285) had a surgical procedure and 46% (132 of 285) were medically managed.13 Of the 334 patients included in the study, 93 (28%) were pain-free and off medication. The largest group that was pain-free and off medication were those who had undergone first-time surgery (84 patients, or 55%). Of the 49 patients undergoing surgery for a second time, only 11 (22%) were pain-free and off medication, and of the 116 who remained on medication alone (18 patients, or 16%) were pain-free and off medication due to remissions.13

These guidelines are based on other documents first published by the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Sciences in 2008,14 which were further updated by the European Academy of Neurology in 2019.10 They are also in line with the care pathways published by a Danish group in 201515 and a U.K. group in 2020.12,16 All agree on the need for more research.

These guidelines help patients to choose and clinicians to develop the optimal care pathway using available evidence. If the appropriate expertise is available, some patients with TN should be managed in a multidisciplinary primary care setting. When such services are not available or adequate, access to specialist management may be delayed and fragmented.17 Streamlining this process should allow faster access to the most appropriate services for individual patients. There is also the recommendation for all clinicians managing this condition to collect long-term outcomes data and disseminate best practices to improve the quality of care.

The guidelines depend on accurate phenotyping of TN. As there are no specific diagnostic tests, clinical assessment is crucial and must be undertaken by experienced clinicians. Many conditions can mimic TN, especially painful trigeminal neuropathy. The pathophysiology and management of trigeminal neuropathy is different, although it may coexist with TN, especially after failed surgery.

Another condition that often coexists with TN is temporomandibular disorder. This is a nociceptive pain condition but may have elements of sharp, shooting pain triggered by eating, talking or brushing teeth.18 It is important to correctly identify the causes triggering pain even in patients known to have TN.

TN may be on the spectrum of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, a group of disorders in which autonomic features such as conjunctival redness, tearing, meiosis, eyelid-dropping and nasal congestion are noted. These include short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with autonomic features (SUNA).19 In some patients, one condition may evolve into another over time. The drug treatment of these conditions may overlap, although the role for surgery is less well defined for trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, and occipital nerve blocks that may alleviate SUNCT or SUNA do not work for TN.20

In the U.K., many patients do not reach specialist centers for four to 10 years after symptom onset, and this increases the risk of developing anxiety, depression and sleep disorders.5 These psychologically traumatized patients with TN have increased suicide risk, and it is important to recognize this so that they are offered additional support not previously mentioned in these guidelines.21,22

Dr. Bahra has disclosed consulting for Pfizer. Dr. Zakrzewska has disclosed consulting for Biogen and Noema Pharma. Dr. Chong reports no relevant financial relationships that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest in the context of contributions to this article.

1. Mueller D, Obermann M, Yoon MS,et al. Prevalence of trigeminal neuralgia and persistent idiopathic facial pain: a population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(15):1542-1548.

2. Katusic S, Beard CM, Bergstralh E, Kurland LT. Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(1):89-95.

3. Maarbjerg S, Gozalov A, Olesen J, Bendtsen L. Trigeminal neuralgia — a prospective systematic study of clinical characteristics in 158 patients. Headache. 2014;54(10):1574-1582.

4. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211.

5. Zakrzewska JM, Wu J, Brathwaite TS. A systematic review of the management of trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:291-306.

6. Wu TH, Hu LY, Lu T, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders following trigeminal neuralgia: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:64.

7. Zakrzewska JM, Wu J, Mon-Williams M, Phillips N, Pavitt SH. Evaluating the impact of trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2017;158(6):1166-1174.

8. Jiang C. Risk of probable posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(4):493-504.

9. Royal College of Surgeons of England. Guidelines for the management of trigeminal neuralgia 2021. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/fds/guidelines/trigemina-neuralgia-guidelines_2021_v4.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2023.

10. Bendtsen L, Zakrzewska JM, Abbott J, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(6):831-849.

11. Moore D, Chong MS, Shetty A, Zakrzewska JM. A systematic review of rescue analgesic strategies in acute exacerbations of primary trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e385-e396.

12. O’Callaghan L, Floden L, Vinikoor-Imler L, et al. Burden of illness of trigeminal neuralgia among patients managed in a specialist center in England. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):130.

13. Singhota S, Tchantchaleishvili N, Wu J, et al. Long term evaluation of a multidisciplinary trigeminal neuralgia service. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):114.

14. Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alksne J, et al. AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(10):1013-1028.

15. Heinskou T, Maarbjerg S, Rochat P, Wolfram F, Jensen RH, Bendtsen L. Trigeminal neuralgia — a coherent cross-specialty management program. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:66.

16. Besi E, Zakrzewska J. Trigeminal neuralgia and its variants. Management and diagnosis. Oral Surg. 2020;13:404-414.

17. Allsop MJ, Twiddy M, Grant H, et al. Diagnosis, medication, and surgical management for patients with trigeminal neuralgia: a qualitative study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015;157(11):1925-1933.

18. Durham J, Newton-John TR, Zakrzewska JM. Temporomandibular disorders. BMJ. 2015;350:h1154.

19. Lambru G, Rantell K, Levy A, Matharu MS. A prospective comparative study and analysis of predictors of SUNA and SUNCT. Neurology. 2019;93(12):e1127-e1137.

20. Pareja JA, Álvarez M. The usual treatment of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Headache. 2013;53(9):1401-1414.

21. Petrosky E, Harpaz R, Fowler KA, et al. Chronic pain among suicide decedents, 2003 to 2014: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):448-455.

22. Daniel HC. Role of psychological factors in the experience of trigeminal neuralgia. In: Zakrzewska JM, Nurmikko T, eds. Trigeminal Neuralgia and Other Cranial Neuralgias. Oxford University Press; 2022:195-206.

Dr. Chong is a consultant neurologist with the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, U.K., and a member of the Medical Advisory Committee for the Trigeminal Neuralgia Association UK. Dr. Bahra is a consultant neurologist with the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and with Cleveland Clinic London, both in London, U.K. Prof. Zakrzewska is Professor of Pain in Relation to Oral Medicine, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery; Royal National ENT & Eastman Dental Hospitals, UCLH NHS Foundation Trust; and Cleveland Clinic London, all in London, U.K.

Advertisement

Despite the condition’s debilitating, electric shock-like pain, treatment options are better than ever

The when and how of surgical interventions, and how symptoms may predict likely outcomes

Compassion, communication and critical thinking are key

Add AI to the list of tools expected to advance care for pain patients

Cleveland Clinic study investigated standard regimen

Program participation correlates with reduced use of opioids, X-rays and ED visits

Tapping into motivational interviewing to guide behavioral change

Relieves discomfort, reduces opioid dependency and improves quality of life