Collaborative patient care, advanced imaging techniques support safer immunotherapy management

Checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis is a rare side effect of immunotherapy, but it can be severe when it occurs. Managing this condition can be complex, with potential implications both for other drug toxicities and the patient’s ongoing cancer treatment.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

That’s why a multidisciplinary approach is key, says Cleveland Clinic pulmonologist Michael Smith, MD.

“You need to involve multiple members of the team, because trying to balance the immune effects with the anti-cancer effects is really important,” he says.

Dr. Smith notes that between 1% and 15% of patients on immunotherapy may develop pneumonitis; drugs that have more toxicities overall are more likely to be associated with lung problems, and patients on combined therapies are also at higher risk. Often, the first signs of pneumonitis are picked up on surveillance scans; many patients are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms like cough and shortness of breath.

But when side effects are more severe, they can be life-threatening, he notes. Providers should monitor patients and investigate any concerning symptoms, he says, adding that pneumonitis can sometimes be misdiagnosed as pneumonia or COPD exacerbations, for example.

“Delays in treatment and especially continuing on immunotherapy when someone has active pneumonitis can lead to patients either being hospitalized or winding up in the ICU and potentially having to discontinue treatment altogether,” cautions Dr. Smith.

The best way to diagnose checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis is with a CT scan. Common patterns on imaging include nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, or ground-glass opacities; and consolidations indicating organizing pneumonia.

Providers may also see hypersensitivity patterns, with nodules centered around the airways and thickening of the interlobular septae; a diffuse alveolar damage pattern; or combinations of multiple patterns.

Advertisement

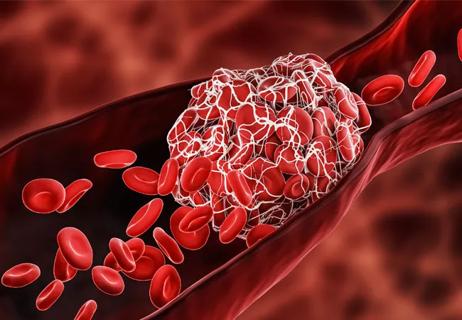

Although toxicities are often first noticed on surveillance scans, if a patient is undergoing testing because they are having symptoms, CT should be done with IV contrast to evaluate for other potential causes, such as pulmonary embolism, Smith adds.

Along with the overall toxicity of treatment, providers should know that certain factors increase risk of pneumonitis. Patients with preexisting lung disease, especially lung scarring or COPD, are more likely to be symptomatic, he notes. Patients with tumors in the lungs, former smokers, and patients with autoimmune conditions are also at higher risk.

Immunotherapies linked with a higher risk of pneumonitis include PD1 inhibitors. Combining multiple immunotherapies, or combining immunotherapy with radiation or chemotherapy, also increases risk.

If a provider knows a patient is at higher risk, involving a pulmonologist early in the treatment process isn’t a bad idea, according to Dr. Smith. Additional specialists should be brought in if immunotherapy reactions are affecting multiple organ systems, he adds.

This approach is helpful not just for monitoring, but also for coordinating treatment.

Dr. Smith recalls a patient receiving immunotherapy for melanoma who developed overlapping lung and skin toxicities.

“She had severe cases of both pemphigus and pneumonitis, and we ran into the problem that rituximab, which is very good for dermatitis, doesn’t do anything for pneumonitis,” he explains. “Then I gave her infliximab, and it flared her dermatitis and pemphigus.”

Advertisement

By working as a multidisciplinary team, they were eventually able to find a regimen that brought the side effects under control.

First-line treatment for checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis is prednisone steroids.

For patients who fail steroid treatment, alternative options include tocilizumab, a biologic that is typically given via subcutaneous injection for patients unable to wean from steroids, or IV infusion for those who are sick enough to be in the ICU and are not responding to steroids at all.

Mycophenolate mofetil, given as a pill twice a day, is another reasonable alternative for patients who are less sick. Additional IV therapies in the ICU include IVIG and infliximab, although the latter has been associated with poor outcomes.

Dr. Smith notes that treatment for checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis is not always necessary: many patients will do well with monitoring alone.

But, he adds, “If you do decide to treat pneumonitis, you should treat it up front, aggressively and quickly.”

In addition to preventing the problem from getting worse, an aggressive approach allows providers to quickly determine whether it’s safe to resume the patient’s cancer treatment. The goal is to see a normal or mostly normal CT scan by the next follow-up, he says.

“Then you can very clearly say to the oncologist, ‘This is cleared up, go ahead.’ Or, you can say, ‘We tried the steroids, and the CAT scan is not getting better. I don’t think it’s a good idea to go back on treatment,’” he explains. “But you won’t know unless you’re aggressive about treating them up front.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Highly personalized treatment shrinks tumors resistant to immunotherapy

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Institute among select group of centers to administer highly personalized treatment

Researchers develop first-of-its-kind neoantigen atlas to better understand immunotherapy resistance

Patients receive specialized inpatient and outpatient care for cellular, gene and immune cell-engaging therapies

Clinicians highlight the need to educate patients about warning signs

Immune toxicity remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and multidisciplinary collaboration remains the cornerstone for early diagnosis and treatment.

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Why Cleveland Clinic is launching its cardioimmunology center