Rising rates in young miners illustrate the need for consistent prevention messaging from employers and clinicians

Written by Maeve MacMurdo, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

While Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis (CWP) may seem like a disease of the past, occupational exposure to coal mine dust continues to pose significant risks to the health of U.S. coal miners. In the past twenty years, we have seen a significant rise in the rates of new CWP diagnoses. Nationwide, more than one in 10 active coal miners show imaging abnormalities consistent with CWP. In central Appalachia, the burden is even greater, with more than one in five miners affected. 1

Simultaneously, we have seen a concerning and significant increase in rates of the most severe form of CWP, known as progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). This trend is particularly pronounced among younger coal miners.2 Even more worrisome is that we are likely underestimating the true prevalence of the disease since a significant proportion of coal miners do not participate in CWP screening programs.

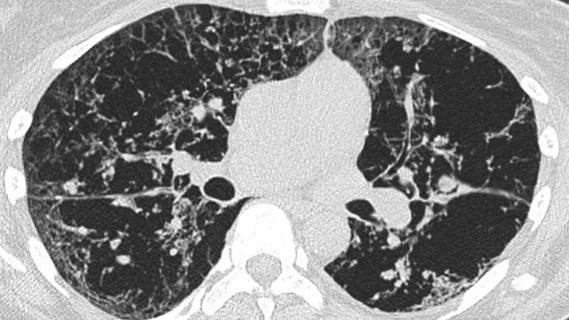

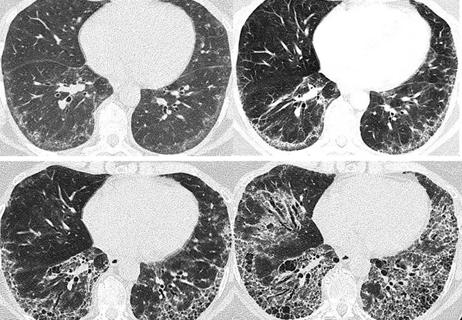

Coal mine dust is a complex mixture of coal dust, respirable crystalline silica and other particulate matter, which can impact respiratory health through multiple pathways (Figure 1). Clinical pneumoconiosis is the classic form of CWP, and it is characterized by the development of fibrotic nodules. This can be further subdivided into small opacity pneumoconiosis (nodules < 1cm in size) and progressive massive fibrosis, where nodules coalesce and form large fibrotic masses.3 Both small opacity pneumoconiosis and PMF can cause significant respiratory impairment.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/88fd4f21-3bfe-46b3-9195-d7cc15afef0c/coal-dust-disease)

Figure 1: Spectrum of lung disease caused by coal mine dust. (A) Progressive Massive Fibrosis with evidence of air trapping. (B) Severe emphysema. (C) Peripheral interstitial reticular fibrosis and mild traction bronchiectasis in a patient with diffuse dust fibrosis. (D) Bilateral pulmonary infiltrates in a patient with connective tissue disease-interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Legal pneumoconiosis refers to the growing range of other lung diseases linked to occupational exposure to coal mine dust. There is strong evidence that workers exposed to coal mine dust have an increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which may occur even in the absence of clinical pneumoconiosis.4 Coal mine dust can also lead to the development of pulmonary fibrosis, a condition known as “diffuse dust fibrosis”, which may be mistaken for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of a thorough occupational history.3 More recently, growing data suggest that exposure to respirable crystalline silica (a major component of coal mine dust) can increase the risk of autoimmune lung disease, including conditions such as sarcoidosis and scleroderma.5 These findings reiterate the importance of a thorough occupational history since the work-related nature of these conditions may be missed or underestimated.

Advertisement

While the lung damage caused by CWP is not reversible, treatments exist that can improve quality of life and potentially decrease the rate at which fibrosis progresses. Therapies such as pulmonary rehabilitation can improve functional status and quality of life, though access remains limited in rural areas.

Particularly in patients with an element of airway disease, targeted inhaled therapy can also help to improve symptom burden and quality of life. But consideration of how these medications are delivered is an important and often underrecognized factor. Dry powder inhalers require a peak inspiratory flow of at least 30 L/min for adequate drug delivery. Achieving this may be a challenge, particularly for those patients who have both obstructive and fibrotic disease from their coal mine dust exposure.6 Nebulized or hydrofluoroalkane inhalers may be an effective alternative, particularly if combined with devices, such as spacers, to minimize technique barriers to inhaler use.

There is growing interest in the use of antifibrotic agents, such as pirfenidone and nintedanib, to potentially slow progression in coal miners with progressive massive fibrosis and diffuse dust fibrosis. While no direct clinical trials are evaluating the use of these agents in patients with CWP, patients with fibrotic lung disease caused by coal mine dust were included in studies of both nintedanib and, more recently, nerandomilast.7,8 Both of these agents have been shown to effectively reduce the risk of forced vital capacity decline, though their impact on quality of life is less clear.

Advertisement

Given the lack of curative treatments, prevention remains the most effective strategy. Proven methods exist to reduce coal mine dust exposure at the worksite, potentially lowering the incidence of this fatal disease. However, the future of these protections is uncertain. In late 2024, the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) issued a final rule to lower allowable exposure to respirable crystalline silica.9 This regulation, a key step in reducing CWP risk, is now facing legal challenges that put its implementation in doubt.

Today, coal mine dust continues to pose a serious health threat to miners across the U.S. Addressing this crisis requires action both at the coal face, where exposure occurs, and in the clinic, where recognizing the full spectrum of coal dust-related disease is essential to delivering effective care.

References

Advertisement

Advertisement

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Multidisciplinary focus on an often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated pulmonary disease

Management and diagnostic insights from an infectious disease specialist and a pulmonary specialist

Treatments can be effective, but timely diagnosis is key

A Cleveland Clinic pulmonologist highlights several factors to be aware of when treating patients

Patient experience improves with a multidisciplinary approach

A mindset shift has changed the way pulmonologists both treat and define PFF

Collaborative patient care, advanced imaging techniques support safer immunotherapy management