A seminal 1956 operation introduced the potential of potassium-induced cardioplegia

Most of the 500,000 heart operations undertaken annually in the U.S. are performed with potassium-induced cardioplegia and thus have roots reaching back to a seminal operation performed at Cleveland Clinic in the early weeks of 1956.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

As Cleveland Clinic continues to commemorate its centennial in 2021, Consult QD looks back on that milestone operation and its legacy for both the patient and the cardiovascular disciplines.

A 9.5-month-old male infant was referred to Cleveland Clinic in May 1955 for failure to thrive, inability to sleep lying flat, and recurrent episodes of pulmonary edema and what was described as “pneumonia.” His evaluation eventually led to cardiac catheterization, which revealed a high ventricular septal defect and pulmonary hypertension.

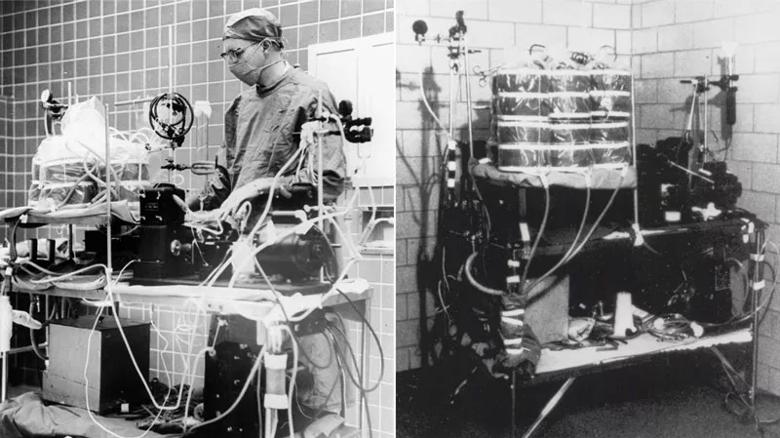

The catheterization was performed by F. Mason Sones, MD, the Cleveland Clinic cardiologist who three years later pioneered coronary angiography. Dr. Sones advised the patient’s parents of research by cardiothoracic surgeon Donald Effler, MD, on the use of a cardiopulmonary bypass pump (Figure 1) designed by Cleveland Clinic’s Willem Kolff, MD, PhD, to close heart defects. Despite being informed that the operation carried a 25% to 30% risk of death, the child’s parents agreed to proceed with surgery to repair the defect using the pump.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/069fdfe1-8e54-4553-ad53-88e1e87b23b9/21-HVI-2182731-CQD-Inset-1-heart-lung-machine-1_jpg)

Figure 1. The early heart-lung machine developed by Cleveland Clinic’s Willem Kolff, MD, PhD. Photo courtesy of Cleveland State University.

The boy was 17 months old when he underwent the operation in February 1956, weighing just 17 pounds. Case notes reveal that Dr. Sones ordered “fresh whole blood” and that the patient be started on antibiotics. Once Kolff’s early heart-lung machine was pumping blood and oxygen, a dose of potassium citrate temporarily paralyzed the boy’s heart.

Advertisement

The surgery (Figure 2) was led by Dr. Effler and Larry Groves, MD, who noted that the pulmonary artery was significantly enlarged, under high pressure and located in an unusually anterior position in the chest. The surgeons used a transverse chest incision, tied off the distal left subclavian artery and used the proximal subclavian for arterial inflow with caval cannulation and caval occlusion. Employing a trans right ventricle approach, they closed the ventricular septal defect — described in operative notes as “the size of a 5-cent piece” — with four interrupted silk sutures. Total pump time was 17 minutes.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/80ea5fda-7b9f-44f3-8a3f-a9fc4e5668ad/21-HVI-2182731-CQD-First-stopped-heart-operation-Hero-2_jpg)

Figure 2. As observers look on, Cleveland Clinic surgeons Donald Effler, MD, and Larry Groves, MD, perform a stopped-heart operation in 1956 using the heart-lung bypass machine developed by Willem Kolff, MD, PhD. Photo courtesy of Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University.

After the heart was reperfused, spontaneous sinus rhythm returned. A lung biopsy was obtained after weaning, but closure was otherwise uneventful. Apart from a fever of 103 degrees Fahrenheit — possibly due to aspiration and relieved with suction — the boy’s postoperative recovery was unremarkable and he was discharged six days after surgery.

By the time the boy was 3 years old, his height and weight had reached normal levels. He returned to Cleveland Clinic from out of state for monitoring at least yearly until he was 14, and he was among the earliest patients to be assessed with the coronary angiographic techniques that Dr. Sones developed in 1958. Now 66 years old, the patient (Figure 3) is a retired professional trumpeter and grandfather who notably has not experienced any cardiovascular events since his surgery as a 17-month-old.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ea0fc5a6-16d6-44dd-8c99-a1d259ca25ca/21-HVI-2182731-CQD-Inset-2-Patient-today-1_jpg)

Figure 3. The case patient today, at age 66.

This case — the first documented operation in which a patient’s heart was stopped with aortic occlusion and potassium citrate infusion on a cardiopulmonary bypass pump — was instrumental in establishing stopped-heart surgery as a regular practice.

“With a dry, quiet, clearly visible field in which to work, we believe that a new era of heart surgery has opened,” observed Dr. Effler soon after the operation.

His remark proved prescient, notes Lars Svensson, MD, PhD, Chairman of Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute.

“Every day, surgeons around the world stop the heart for most types of heart surgery using a process similar to the one pioneered by Drs. Effler and Groves at Cleveland Clinic in 1956,” says Dr. Svensson. “Even today, closing a hole in the heart in 17 minutes is remarkable. This case is a reminder that the pioneers of cardiac surgery were heroes for attempting operations with uncertain outcomes. The innovation and commitment embodied by this milestone stopped-heart operation are qualities we continue to emulate at Cleveland Clinic to the present day.”

For more insights from Dr. Svensson on this pivotal operation, watch this 11-minute video.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Initial data indicate tolerability and promising cardiac remodeling effects

LLM-driven system uses both structured and unstructured data, provides auditable justifications

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most