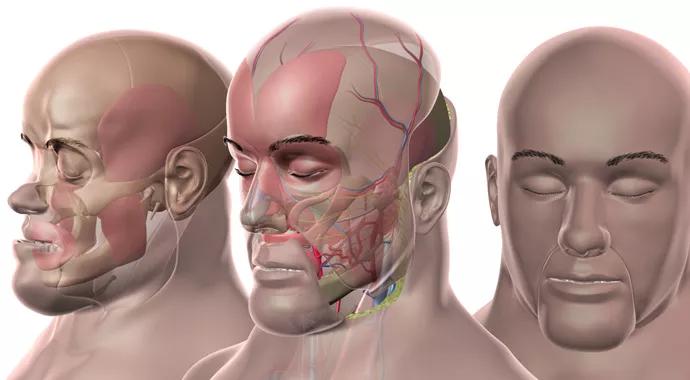

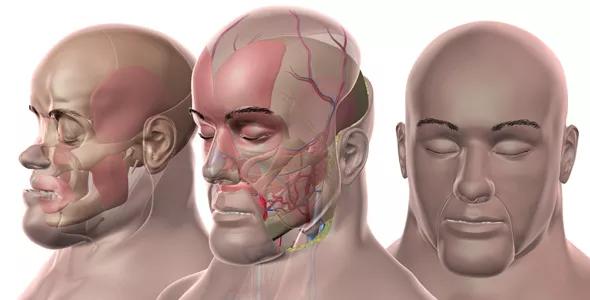

First inclusion of bilateral internal maxillary arteries and their terminal branches for vascularity to the upper face

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1fc7cce0-ce8d-4672-98f5-51a6d49c6d93/transplant-complete_690x380_jpg)

transplant-complete_690x380

A multidisciplinary team of Cleveland Clinic surgeons and transplant specialists performed a near-total face transplant earlier this autumn in a middle-aged man who suffered facial trauma and other complications as a result of a motor vehicle accident.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The 24.5-hour surgery was successful, with excellent prospects for flap survival, and the patient is recovering well more than a month after the procedure. The operation is the second near-total face transplant performed at Cleveland Clinic, where the nation’s first such procedure was successfully completed in 2008.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://www.youtube.com/embed/riEpE4F6hDE?si=qaLLa3Qp6qzYEAFZ)

This latest near-total face transplant is historic in its own right in at least two respects:

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8b563f2b-93c8-49f2-b78d-d524f36b25ad/transplant-complete_590x300_jpg)

“The graft included about two-thirds of the scalp, so including the internal maxillary arteries increases the vascularity and robustness of the flap in the scalp and upper face,” explains Francis A. Papay, MD, Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Dermatology & Plastic Surgery Institute, who co-directed the transplant team along with Maria Siemionow, MD, PhD, a consultant staff member who served as an advisor for the case.

“We could have perhaps done this transplant by including just the facial artery,” Dr. Papay adds, “but applying the internal maxillary arteries as well almost guaranteed a technically successful surgery and flap survivability by providing better blood supply. We were well prepared to work with the internal maxillary artery thanks to practice from a multitude of cadaver studies we’ve conducted.”

Advertisement

The case is likewise notable for its ophthalmological aspects. The patient had previously lost his right eye due to the complications stemming from his accident, which included highly progressive facial necrosis. In the months before his transplant, he confronted impending loss of total sight in his left eye as well, as that eye’s lids became contracted and nonfunctional to the point that he wasn’t able to close the eye, leaving it exposed.

“There was a race to cover the patient’s one seeing eye in some way to preserve his vision,” Dr. Papay notes. While the patient waited for a face graft from an appropriate donor, ophthalmologists from Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute protected the exposed left eye with an amniotic membrane and topical ointments.

A donor was identified before the patient lost the eye, and the face transplant included upper and lower eyelids to restore permanent protection for the eye. The patient can now see light, color, shadow and movement. A subsequent surgery is still needed to slightly raise the eye to its proper position in the orbit once the patient gains more eyelid movement. “We couldn’t do too much at once to the eye since that could put tension on the optic nerve and risk blindness,” Dr. Papay explains. A corneal transplant can be considered down the road to further improve the eye’s vision.

The case is also remarkable in that the patient was already on immunosuppressant therapy for an underlying health condition that is not being disclosed at this time to protect the patient’s privacy. “He was already being immunosuppressed before the transplant, so we didn’t introduce that as a new risk with the transplant,” notes Dr. Papay.

Advertisement

Transplant was considered for the patient after multiple attempts at autogenous facial reconstruction did not adequately address the deformities stemming from the complications of his motor vehicle accident.

The procedure involved transplanting approximately 90 percent of the patient’s face (Figure), including about two-thirds of the scalp plus the forehead, upper and lower eyelids, nose, upper cheeks, upper jaw, orbital floor, facial nerves, parotid glands and muscles of facial expression. Tissue types involved included skin, muscles, nerves, arteries, veins and bony structures including the zygomatic arches, zygomatic body, maxilla and all the upper teeth.

The graft was harvested from a healthy male donor in a neighboring operating room and was transplanted directly into the recipient without need for preservation.

The 24.5-hour transplant surgery involved a team of nine surgeons:

Central roles were also played by Bijan Eghtesad, MD, a liver transplant surgeon who has been managing the patient’s post-transplant immunosuppression, and ophthalmologists from Cole Eye Institute who were integral to preservation of the patient’s functioning eye. Many additional Cleveland Clinic experts have been involved in the pre- and postoperative management of this case, as detailed in a related post profiling the roles of the sizable multidisciplinary team required for success.

Advertisement

“Face transplant is the ultimate team sport,” says Dr. Papay. “It takes a collaborative team whose members work in concert. The relationships between team members are incredibly important, and everyone needs to accept his or her role.”

Several weeks after the transplant, the patient has had his tracheostomy tube removed and is able to speak and breathe on his own. His vision is preserved, as detailed above. He will soon have an obturator placed to plug a hole created in the back of his palate during the surgery; once that happens, he can eat solid food and will lose the vocal hypernasality that is characteristic of face transplant patients in the early postoperative stage.

Dr. Papay is confident the patient’s flap is well vascularized, so the primary focus now is carefully monitoring for signs of immune rejection. “Almost all face transplant patients experience rejection to some extent in their initial recovery period,” he says. The transplant team is conducting frequent skin and mucosal biopsies to determine the patient’s risk of rejection and adjust his immunosuppression accordingly, as needed.

“You don’t want to immunosuppress too much,” Dr. Papay cautions, “as that can lead to infections — and potentially sepsis and death.”

“This patient has benefited from all that we learned from our first face transplant and the research we’ve done in its wake,” Dr. Papay notes. Those insights include a comprehensive and unprecedented four-year pathology review of the first transplant, which was published in late 2013. The patient from that first transplant continues to thrive.

Advertisement

Likewise, this new transplant is ideally positioned to contribute to future face transplant advances though its inclusion in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine (AFIRM) grant program to support development of innovative therapies for wounded military personnel. This was the eighth face transplant conducted in the U.S. under the AFIRM grant, which is designed to fund a series of such transplants. Among several U.S. institutions approved to perform face transplants under the grant, Cleveland Clinic is the third to have successfully completed one under the grant so far.

While this case’s contributions regarding the internal maxillary arteries and vision preservation are certain to help advance the AFIRM goals, Dr. Papay says the greatest contributions were still made at the individual patient level: “Our team was privileged to have the opportunity to save a man’s vision and restore much of his overall function. His wife cried for joy when she saw him afterward. The emotions behind a procedure like this are mind-blowing.”

Advertisement

Milestone minimally invasive surgeries reduce pain and recovery time

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Insights on bringing Cleveland Clinic even closer to becoming the best transplant enterprise in the world

Minimally invasive approach, peri- and postoperative protocols reduce risk and recovery time for these rare, magnanimous two-time donors

Minimally invasive pancreas-kidney replacement reduces patient’s pain, expedites recovery

First-ever procedure restores patient’s health

Smaller incision may lead to reduced postoperative pain for some patients

Improving access to lifesaving kidney transplant