Smaller incision may lead to reduced postoperative pain for some patients

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2447efdb-9eb5-4878-8b73-11cb3f73595a/23-URL-3973558-CQD-650x450-B_jpg)

23-URL-3973558 CQD 650×450-B

Several years ago, the kidney transplant surgeons at Cleveland Clinic adopted a new, less invasive incision for kidney transplant called the anterior rectus sheath approach (ARS). They now use the approach in almost 90% of kidney transplant cases. And while, anecdotally, the incision offers improved pain outcomes, there was no scientific evidence to corroborate that — until now.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Dr. Eltemamy and Cleveland Clinic colleagues led a single-center prospective trial that randomized 75 patients into one of two incision cohorts: the smaller, muscle-splitting ARS approach versus the conventional muscle-cutting Gibson approach. Study participants were followed for a minimum of one year following transplantation. The authors published findings from the trial in Clinical Transplantation.

“Previous studies have demonstrated the benefit of ARS in patients with obesity, but ours was the first to implement the approach in a larger cohort, without the exclusion of obesity, and evaluate outcomes alongside the Gibson approach,” says Dr. Eltemamy.

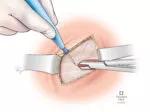

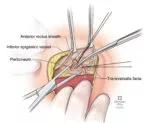

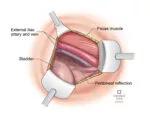

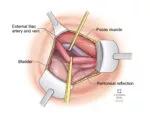

The ARS approach offers a cosmetic advantage over the Gibson approach, although the study was not powered to evaluate aesthetic outcomes. The ARS approach includes a 7 cm to 12 cm oblique skin incision 2 cm to 5 cm above and parallel to the inguinal ligament. It’s typically half or less than half the size of the conventional incision.

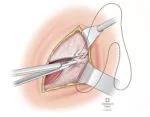

The authors note that the technique involves a muscle-splitting approach to the iliopsoas fossa, in contrast to the muscle-cutting Gibson approach. They also provide supplementary video of the technique in their paper as well as step-by-step instructions on performing the ARS, as demonstrated in the below illustrations.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4b892a1f-128a-41ba-9a1d-0a3c2c3cdb25/incisions-lower-ab_renal-transplant-1_20-URL-1991010-150x112_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d8e519a6-58f2-445a-b7d2-2d7b9d21b8ee/mini-renal-transplant_opening-incission-3_20-URL-1991010-150x112_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1e7a5116-7f18-4d50-802f-2dd889fd4679/mini-renal-transplant_opening_artery-4_20-URL-1991010-150x123_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3f48726e-a410-4292-a5b9-a49e2a388f55/mini-renal-transplant_deep-opening-5_20-URL-1991010-150x117_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3a8371b4-4aa2-4f46-b39f-a34f85607ca9/mini-renal-transplant_isolate-artery-vein-6_20-URL-1991010-150x117_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/16bd44ca-01f3-4562-96e7-184153f3c382/mini-renal-transplant_isolate-amastomosis-7_20-URL-1991010-150x131_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/641bc0a5-5cad-44eb-8113-a8f12a3fb734/mini-renal-transplant_perfusion-8_20-URL-1991010-150x133_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/69c9825c-d512-4c9d-8442-f2e294b257ed/mini-renal-transplant_bladder-anastamosis-9_20-URL-1991010-150x114_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d0620e3b-dc65-4b73-89b2-ecb919e973fb/mini-renal-transplant_final-closure-10_20-URL-1991010-150x117_jpg)

Slide 1/9

In addition to pain outcomes, the investigators also evaluated wound-related complications (WRC) associated with each approach, although they did not find a notable difference between the two cohorts (P = .23). Still, Dr. Eltemamy emphasizes the importance of surgeon-led efforts to minimize risk for WRC. This is particularly germane in the context of rising annual rates of kidney transplantation and the increasing comorbidity burden within the patient population.

Advertisement

The approach does not require specialized technology or expertise in laparoscopic of robotic surgery to perform. What does it require? Dr. Eltemamy says, “A modest investment in small, slim profile retractors to make the incision possible and the initial learning curve. That’s all it takes.” In terms of exclusion criteria, he explains there are two scenarios he would likely avoid the ARS: when patients have severe calcifications of the external artery that require a higher incision or in cases when more complex vascular reconstruction is warranted.

Dr. Eltemamy and colleagues have also completed a follow-up analysis examining the ARS in conjunction with transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block, an intraoperative analgesic. While this study is pending final publication, it represents continued efforts from the Cleveland Clinic team to explore improved patient outcomes following kidney transplant.

“Our goal is to get to a point where patients won’t need any narcotics following kidney transplant — and we think that’s a near-future reality,” concludes Dr. Eltemamy.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Surgeons choreograph nearly simultaneous procedures, sharing one robot between two patients

Key findings and proposed clinical interventions for affected areas

Improving access to lifesaving kidney transplant

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more

Milestone minimally invasive surgeries reduce pain and recovery time

Veteran nurse blends compassion, cutting-edge transplant training and military tradition to elevate patient care

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Insights on bringing Cleveland Clinic even closer to becoming the best transplant enterprise in the world