Early detection, prognostication and intervention may improve outcomes

Multidisciplinary perspectives on the importance of early referral and more

For patients with headache, pulsatile tinnitus or vision changes, immediately stop use and refer to ophthalmology

Family history may eclipse sun exposure in some cases

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Consider secondary syphilis in the differential of annular lesions

Persistent rectal pain leads to diffuse pustules

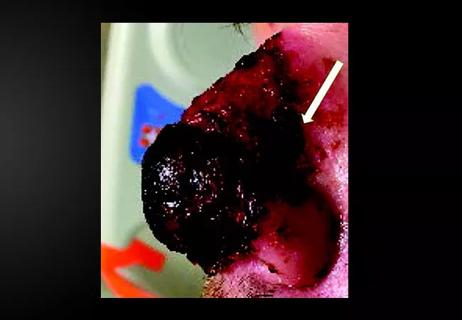

Two cases — both tremendously different in their level of complexity — illustrate the core principles of nasal reconstruction

Unique skin changes can occur after infection or vaccine

Stress and immunosuppression can trigger reactivation of latent virus

Low-dose, monitored prescription therapy demonstrates success

Advertisement

Advertisement