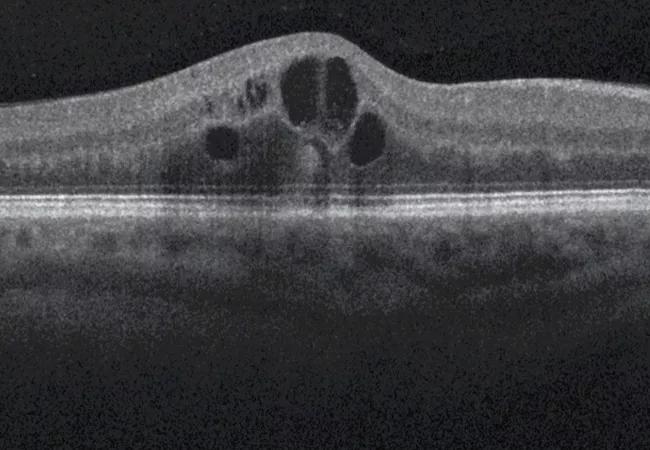

Greater central subfield thickness and better visual acuity at baseline are associated with longer time to resolution

According to 2018 statistics, more than 34 million people in the U.S. are affected by diabetes mellitus. By 2030, this number is projected to increase to 41.7 million. Diabetic macular edema (DME) is a common complication of longstanding diabetes and associated diabetic retinopathy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A recent study led by Cleveland Clinic investigators aimed to assess the relationship between baseline factors and time to resolution of DME in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes treated with intravitreal aflibercept injection (IAI). Study results were published in Ophthalmology Retina.

“There is not a lot of data on how quickly it takes DME to go away and how long patients must remain on treatment,” says ophthalmologist Katherine Talcott, MD, of Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute, the study’s corresponding author. “We wanted to figure that out as well as identify factors that impact how quickly a patient with DME responds to treatment.”

The post hoc analysis was performed on data gathered for patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus and central DME involvement from two phase 3 clinical trials, VISTA and VIVID. The trials were similarly designed and conducted at 127 centers across the U.S., Australia, Europe and Japan.

“This was a nice opportunity to take advantage of these larger studies and glean more information on intravitreal aflibercept, one of the most common treatments for DME,” says Dr. Talcott. “Macular edema is one of the most common ocular conditions that we see and treat in patients with diabetes.”

To be eligible for enrollment in VISTA or VIVID, each patient had at least one eye with best-corrected visual acuity between 73 and 24 letters. Eyes were randomized 1:1:1 to three groups: IAI 2 mg every four weeks, IAI 2 mg every eight weeks after five initial monthly sham injections or no treatment, and laser plus sham injections (control group). Treatment was continued through week 96. Starting at week 24, all patients were eligible for rescue treatment.

Advertisement

The post hoc study’s primary outcomes were the time to and cumulative incidence of the first DME resolution and first sustained DME resolution. Also assessed was the link between time to first DME resolution and multiple baseline characteristics, including age, race, sex, ethnicity, type and duration of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hemoglobin A1c level, smoking status, diabetic retinopathy severity score, central subfield thickness and best-corrected visual acuity.

Dr. Talcott notes that the time to DME resolution was rather long, and only about three in four patients achieved resolution by the second year.

“In one year, about 59% of patients had resolution of macular edema. By two years, it was only 74%,” she says. “That means that the swelling does not go away in a lot of patients, even when they’re getting very aggressive treatment. That was eye-opening for us because we assumed the fluid would dissipate in more people.”

The median time to edema resolution was 33 weeks.

“It is helpful to know that if someone will have resolution, it’s going to take the greater part of a year,” says Dr. Talcott.

DME resolution took longer if a patient had more macular edema (as evidenced by greater central subfield thickness) or better vision at baseline. There was no association between time to resolution and level of hemoglobin A1c at baseline.

“The concept that more fluid takes more time to clear is logical,” says Dr. Talcott. “However, we struggled a little with understanding why better vision would be linked with longer resolution time. Eventually, we theorized that people with good vision are less likely to see their eye doctor or come in for DME treatment.”

Advertisement

She adds that patients in this study who had better vision had DME longer than patients whose vision was not as good.

Dr. Talcott says her research group next plans to study whether these findings hold true for other classes of medications for DME, including steroids.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Study identifies factors that may predict vision outcomes in diabetic macular edema

Flaps, blebs and other surgical options

Can a single subretinal injection provide effective treatment?

New insights on effectiveness in patients previously treated with other anti-VEGF drugs

Evidence mounts that these diabetes and obesity drugs may protect eyes, not endanger them

CFH gene triggers the eye disease in white patients but not Black patients

A primer on sustained release options

Study explores association between sleep aid and eye disease