What we've learned over the past two decades

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2cf39a24-b56b-41f0-94e9-0f51656845ad/650x450-3D-MR-kindey_jpg)

650×450-3D-MR-kindey

By Ali Mehdi, MD, MEd;Jonathan J. Taliercio, DO; and Georges Nakhoul, MD, MEd

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Editor’s note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. This is the second article of a two-part series. The article in its entirety, including a complete list of references, can be found here.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a debilitating and often-fatal fibrosing disease characterized by skin thickening and organ fibrosis.29 It was first reported in 15 dialysis patients in San Diego in the year 2000.30 However, the relationship between NSF and the use of gadolinium as contrast during MRI remained obscure for a long time, finally being suggested six years later in Europe.31

The postulated mechanism was the deposition of toxic free gadolinium molecules in the tissues32 with subsequent increases in circulating fibrocytes,33 an increase in the expression of transforming growth factor beta 1,34 and release of proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines.35 Eventually, gadolinium was detected by electron microscopy on a skin biopsy specimen, specifically in areas of calcium phosphate deposition in blood vessels.36

By 2009, the disease was well established, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had received over 500 reports, most of them from the United States37 and Denmark.38

In response to this crisis, the authorities and radiology societies were quick to react. In 2007, both the FDA39 and the European Medicine Agency40 issued warnings highlighting the risk of NSF associated with the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents. The American College of Radiology,41 European Society of Urogenital Radiology,42 and other radiology societies published guidelines and recommendations on how to use gadolinium-based contrast agents, particularly in patients with kidney disease.

Advertisement

Gadolinium agents that have a linear molecular shape pose a higher risk, and their use was contraindicated in patients with acute and severe chronic kidney disease with eGFRs less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 , as well as in patients on dialysis. Additionally, evidence that gadolinium-based contrast agents are removed with dialysis43 prompted clinicians to change their clinical practice by offering dialysis to patients with advanced kidney dysfunction who were exposed to these agents.

As a result of those measures, the number of cases of NSF was drastically reduced. The last reported case in the United States dates back to 2010, and the last report in the world was in 2012.44

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been used since the 1980s and were initially thought to have an excellent safety profile.45 This led to their liberal and preferential use compared with iodine-based agents, particularly in patients with reduced kidney function.46 However, their incriminating role in NSF highlighted their potential toxicity.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents share a common structure, with a central heavy metal ion (gadolinium) bound tightly by an organic ligand to form a stable complex, thus minimizing the potential natural toxicity of the free metal ion.47 To avoid gadolinium toxicity, these agents should be highly stable so the gadolinium does not dissociate. Their stability is conferred by their chemical structure, namely whether they are linear or cyclic and whether they are charged (ionic) or electrically neutral (nonionic).48 It is generally recognized that macrocyclic and ionic structures are more stable than linear and nonionic ones.49 Thus, in highly stable agents, gadolinium dissociation is minimized and so is the risk of NSF.

Advertisement

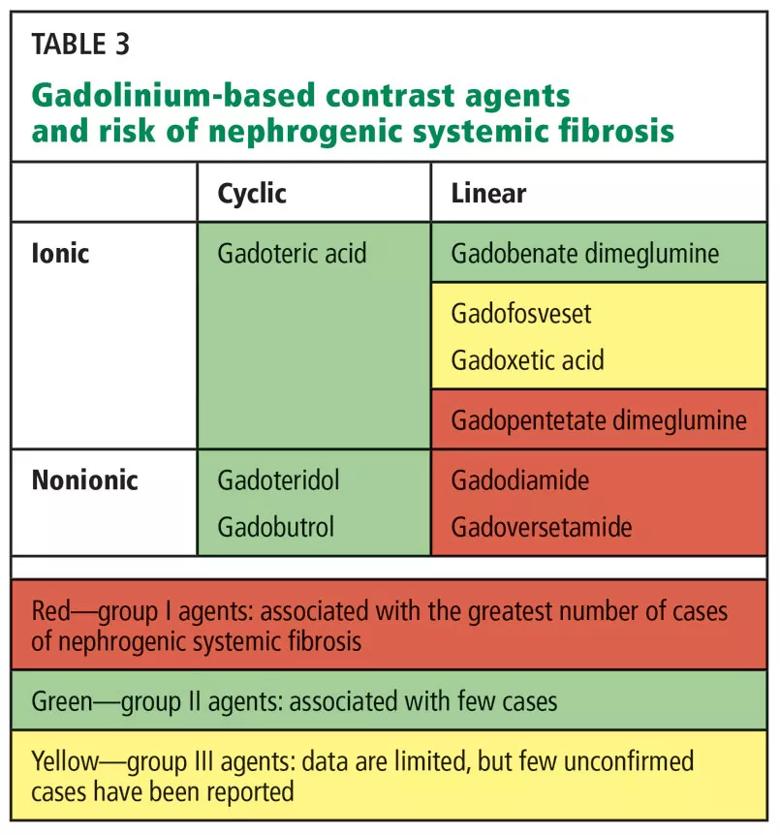

On the basis of their NSF risk (and specifically on the numbers of unconfounded single-agent cases of NSF recorded for each agent), the nine available gadolinium-based contrast agents are grouped into three groups (Table 3). 41

It is generally accepted that groups I and III should be avoided in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b682da8f-4c22-490c-984f-d19a20cb6375/805x-Table-3_jpg)

The guidelines set by the FDA and the radiology societies were undoubtedly effective in curbing the disease and eventually eliminating it. A recent review of 639 patients with biopsy-proven NSF from 173 articles estimated that the risk of NSF per million exposures had decreased from 2.07 before 2008 to 0.028 afterward.50

Most cases were associated with exposure to group I agents. However, those guidelines were applied to all gadolinium-based contrast agents without considering their stability or association with NSF. The downside of this approach was the denial of clinically indicated contrast-enhanced MRI in patients with severe kidney disease, with a subsequent potential real (though unmeasured) harm resulting from misdiagnosis or diagnostic delay.51

In recent years, evidence has been accumulating as to the safety of group II agents. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the pooled risks of NSF in patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease receiving a group II gadolinium-based contrast agent.52 The authors analyzed 16 studies with 4,931 patients who received group II agents. The pooled risk of NSF was 0% (upper bound of 95% CI 0.07%). Thus, they estimated the per-patient risk of NSF from receiving group II gadolinium-based contrast agents in stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease to be less than 0.07%. This risk is much smaller than that of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who receive iodinated contrast,53 and thus argues for a better safety profile of contrast-enhanced MRI using group II agents. In fact, the risk appears to be comparable to that of developing a severe allergic reaction to contrast agents, which is estimated at 0.04% for low-osmolality iodinated contrast agents54 and 0.002% to 0.006% for group II agents.55

Advertisement

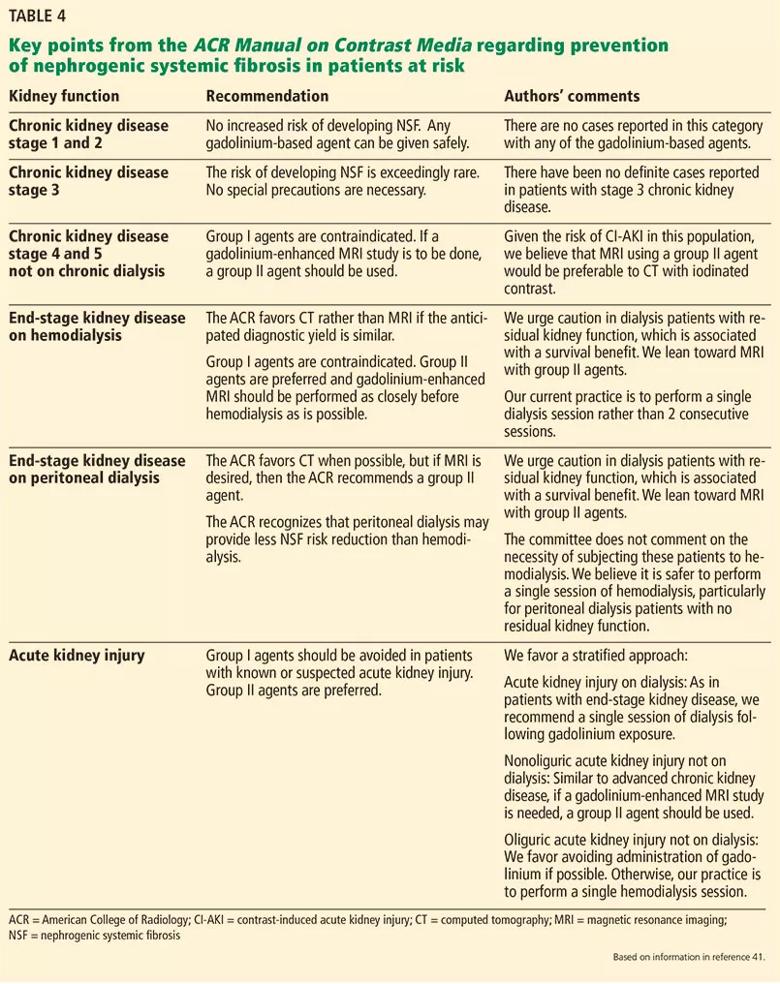

On the basis of accumulating evidence,56–60 the recent guidelines of the American College of Radiology,41 the European Society of Urogenital Radiology,61 and the Canadian Association of Radiologists48 all permit the use of group II gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with advanced kidney disease. The American College of Radiology41 defines patients at risk of NSF as those:

In these patients, group I and III gadolinium-based contrast agents are contraindicated, with the caveat that there is insufficient real-life data to determine the risk of NSF from administration of group III agents. In patients at risk, if a gadolinium-enhanced MRI study is to be performed, a group II agent should be used. The lowest dose required to obtain the needed clinical information should be used, and it should generally not exceed the recommended single dose. A summary of those recommendations with our comments and opinions is provided in Table 4. 41

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d9596090-1d76-4c70-a8dd-3533dd2717fa/805x-Table-4-1_jpg)

Although NSF has been basically eradicated since the guidelines were implemented, several cases of NSF have been reported in patients who never were exposed to gadolinium. In a review of biopsy-proven cases of NSF reported in 98 articles, 27 (8%) of 325 patients had no clear exposure to these agents,62 and in the review of 639 biopsy-proven cases discussed above, 14 (2%) did not.50 This suggests that gadolinium-based contrast agents are a major trigger for NSF, but they may not be the only one. Time will tell if indeed other triggers have yet to be discovered.

Advertisement

Additionally, in recent years, there have been data suggesting that gadolinium can deposit in the brain after repeated exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents, even in patients with healthy kidneys.63 This finding was confirmed histologically64 and has led to the birth of a new term to describe it: gadolinium deposition disease.65 The significance of this brain deposition remains unknown, and to date, no adverse health effects have been uncovered. However, the FDA published a safety alert in 2015 indicating the active investigation of the risk and clinical significance of these gadolinium deposits. The recent position statement of the American College of Radiology also recognizes this phenomenon and states, “Until we fully understand the mechanisms involved and their clinical consequences, the safety and tissue deposition potential of all [gadolinium-based contrast agents] must be carefully evaluated.” 66

It thus appears that we haven’t heard the last of gadolinium-based contrast agent-related disease. Additional research will be needed to understand the potential consequences of the use of these agents.

Advertisement

Pediatric urologists lead quality improvement initiative, author systemwide guideline

Fixed-dose single-pill combinations and future therapies

Reproductive urologists publish a contemporary review to guide practice

Two recent cases show favorable pain and cosmesis outcomes

Meta-analysis assesses outcomes in adolescent age vs. mid-adulthood

Proteinuria reduction remains the most important treatment target.

IgA nephropathy is a relatively common autoimmune glomerular disease that can be diagnosed only by biopsy

Oncologic and functional outcomes are promising, but selection is key