By Nicole Bajic, MD, and George Markakis, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Glaucoma is a silent killer of vision. It’s the second leading cause of blindness in the world and a top cause of irreversible blindness.

It’s also expensive. Glaucoma affects millions of people in the U.S. at an annual cost of $2.86 billion, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Historically, topical hypotensive medications (eye drops) have been the first-line therapy for glaucoma, followed by laser treatment and incisional surgery. However, all three of these treatments pose concerns:

- Eye drops can be a cost burden to patients as well as a time burden. Some patients struggle with treatment compliance. Drop efficacy varies. There is potential for adverse reactions to drops, such as dry eye, allergic conjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. The cost of drops can make them unaffordable for some patients.

- Laser treatment is not always effective. It can fail over time. It often produces only a small drop in intraocular pressure (IOP) and comes with a risk of IOP spikes and reactivated uveitis.

- Incisional surgery comes with a risk of hypotony, choroidal effusion and choroidal hemorrhage. IOP is more unstable after incisional surgery. Patients have a higher lifetime risk of infection.

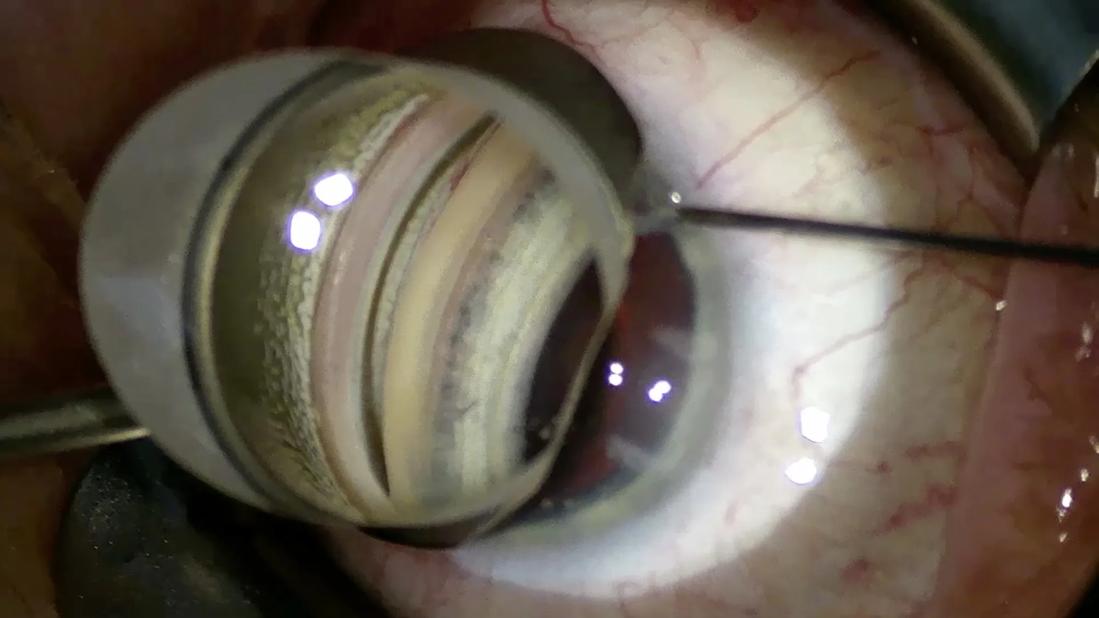

On the other hand, microinvasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) can provide more consistent and significant IOP lowering to get patients off eye drops. MIGS enhances physiological outflow mechanisms without major alterations to ocular anatomy. It comes with low risk of serious complications. By performing the procedure ab interno, you have direct visualization of the anatomical target and can get instant feedback on success (by blanching of episcleral vessels). Additionally, patients can have MIGS at the same time as cataract surgery, with a generally quick recovery, minimal additional downtime and minimal increase in complication rate compared with cataract surgery alone.

Before or after phacoemulsification?

Performing MIGS before or after phacoemulsification is a matter of preference.

If you opt to perform MIGS after phacoemulsification, the angle will be more open, but there can be other disadvantages:

- It may be harder to maintain the anterior chamber. Viscoelastic tends to leak out.

- Unintended stromal hydration can obscure your view.

- If you encounter complications during cataract surgery (e.g., posterior capsular rupture), you are more likely to forgo the MIGS procedure.

7 keys to success

For comprehensive ophthalmologists who have never performed angle surgery: You don’t know what you can do until you try. Follow these tips to get started with MIGS:

- Select patients appropriately. Ideal patient selection — patients with high myopia or highly visible angle anatomy on preop gonioscopy — can make the learning curve easier. Patients with mild to moderate primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) can benefit from either stents, goniotomy or canaloplasty. In the U.S., due to insurance coverage, patients with ocular hypertension may be eligible for only goniotomy or canaloplasty. Patients with kyphosis, deep-set orbits, or lids with small fissures or scarring can make the surgical procedure challenging.

- Perform a thorough gonioscopy prior to surgery. Review the ocular landscape to survey the treatment area and better determine the appropriateness of a MIGS procedure. Narrow angles are generally a contraindication for MIGS. Synechiae and prior laser scars (such as from argon laser trabeculoplasty) can be problematic, making the trabecular meshwork friable and potentially less suitable for stents. A shallow anterior chamber or slightly narrow angles may be better suited for goniotomy.

- Get positioned. Start the case with the surgeon’s chair high and the microscope oculars angled down. Wrist rests should be avoided as your hands should rest on the patient for better stability, allowing you to move with the patient and perform minor positional adjustments as needed. You may want to avoid taping the patient’s head (or do so loosely), as it will need to be tilted to the side during the MIGS portion of the procedure. A surgical donut under the patient’s head can provide some head stability and comfort for the patient without prohibiting head tilt.

- Prep the eye and perform paracentesis and clear corneal incision (CCI) as normal. Visualization and patient positioning are key. If performing MIGS that requires an accessory paracentesis, positioning of this is also very important. When implanting a Hydrus® Microstent, an accessory paracentesis must be made to the dominant-hand side of the CCI, and it should be angled tangentially (not radially) toward the target trabecular meshwork. Using a wired, angled Lieberman speculum can be useful as it is less likely to impede the Hydrus inserter.

- Use trypan blue, viscoelastic and/or hydroxypropyl methylcellulose. Staining the trabecular meshwork and anterior capsule with trypan blue can be advantageous and should be done for your first few MIGS cases. The trabecular meshwork will be highlighted, which is especially useful in patients who have little to no pigmented meshwork. This also can aid in visualization of the capsule during capsulorhexis, especially in the case of hyphema. The use of sodium chondroitin and/or sodium hyaluronate (e.g., Viscoat®, Healon®) intracamerally not only helps maintain the anterior chamber during the MIGS procedure but also can focally open up the angle for better visualization of the trabecular meshwork and help tamponade heme. Apply a small amount of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (e.g., Goniosol) or leftover viscoelastic to the corneal surface to couple the gonioprism to the cornea for visualization of the angle structures.

- Reposition and proceed with modifying the drainage canals. Good positioning is paramount to your surgical success. Tilt the patient’s head away from you approximately 45 degrees, lower the surgeon’s chair, tilt the microscope oculars up, re-zero the scope and rotate the scope 30 degrees away from you. Focus the scope until the angle structures are clear. You will typically increase magnification to a greater extent than what is used for cataract surgery. (The field of view usually extends only out to the limbus.) If you are not using a hands-free prism, depression with the stabilizer by tilting the prism can open up the angle. However, you should avoid excessive pressure from the gonio lens on the cornea, which could cause egress of viscoelastic from the anterior chamber.

- Provide proper postoperative care. Keep the eye patched until the patient’s visit on postop day 1. Provide strong steroid and NSAID drops to reduce inflammation. Consider a dexamethasone ophthalmic insert (e.g., Dextenza®) as needed. You may want to stop prostaglandin drops to minimize the risk of cystoid macular edema. In patients with mild, well-controlled POAG or low IOP on postop day 1, you may consider discontinuing the IOP drops altogether. In patients with more severe POAG or higher IOP on postop day 1 or in the presence of significant hyphema, use a nonprostaglandin (e.g., brimonidine timolol, dorzolamide timolol).

The MIGS opportunity

If you can do cataract surgery, you can do MIGS.

Given the demonstrated safety and efficacy of currently available procedures, patients with glaucoma who are undergoing cataract surgery should be offered MIGS. There’s minimal additional risk and surgical time when combining MIGS with cataract surgery. It may be a patient’s best chance to stop using eye drops (thereby improving their lifestyle and decreasing financial burden). It also may better control their glaucoma, although it may not rule out future glaucoma procedures.

If you don’t feel comfortable performing MIGS, consider referring your patients to an ophthalmologist who does, so that your patients have the best opportunity for healthy eyes and good vision.

For a primer on MIGS methods and devices, see How to Get Started With Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery (Part 2).

Drs. Bajic and Markakis are comprehensive ophthalmologists at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute.