Maintaining patients' home medication regimens looms large, study suggests

“Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are often hospitalized, and when they are, they face particular challenges,” says Benjamin Walter, MD, MBA, Section Head of Movement Disorders at Cleveland Clinic. “The complexity of their medication regimens, and the effects when these regimens are altered, set the stage for adverse events.”

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In response, Dr. Walter is leading a two-part study designed to identify and quantify the occurrence and impact of deviations from PD medication regimens in hospitalized patients with PD and then to evaluate interventions to avoid such deviations. The study, known as the Parkinson’s Inpatient Quality and Safety Initiative, is supported by a $333,000 grant from the Parkinson’s Foundation.

“Most previous studies in this patient population have focused on how inpatient medication administration deviates from inpatient medication orders,” Dr. Walter notes. “Our current study is looking at deviations between patients’ stable outpatient medication regimens and inpatient administration, along with the impact on complication rates. We believe reducing these deviations is key to substantially improving outcomes when patients with PD are hospitalized. We hope this effort can help set a new standard for combating the national problem of complications among hospitalized patients with PD.”

Up to 25% of patients with PD are hospitalized each year, and they tend to stay in the hospital longer than other patients, suggesting an elevated rate of complications. Often their primary provider — usually a movement disorders specialist — is far from the hospital and thus is less likely to be consulted. Only a small percentage of these patients are hospitalized because of PD itself; instead, most are admitted for falls, pneumonia, encephalopathy, dementia or hypotension with syncope — conditions that often exacerbate parkinsonian symptoms and increase the likelihood that their medication regimen will be changed.

Advertisement

“Patients with Parkinson’s are very vulnerable to entering a downward spiral when admitted to the hospital,” Dr. Walter says.

He adds that maintaining a patient’s home regimen — often involving multiple drugs with precisely timed, complicated schedules — isn’t always easy. For example, substituting one levodopa drug for another poses a risk, as alternate formulations may have different pharmacokinetics. In addition, while at home, a patient may take a drug four times a day during waking hours, but when admission pharmacy orders are written as “QID,” the schedule often becomes every six hours around the clock. Prolonged NPO orders also can disrupt a patient’s medication schedule.

Either too much or too little medication at any given moment can quickly have serious consequences, potentially leading to a fall, swallowing problems or changes to mental status. Moreover, many commonly prescribed medications for hospitalized patients — especially antipsychotics, narcotics and antiemetics — are contraindicated in people with PD because they block dopamine function.

The study’s initial focus was on determining the rate of deviations from home medication regimens and the addition of contraindicated medications for patients with PD admitted to a Cleveland Clinic tertiary care center and regional hospital over a 12-month period. Using 2018 as the reference year, 492 patients with PD or parkinsonism were identified (725 admissions), excluding patients with drug-induced PD, those without information on home medication regimens and those who had less than a 24-hour hospital stay.

Advertisement

Patients in the cohort had mean age of 76.9 years and a mean age at PD onset of 62, suggesting generally advanced disease overall.

This initial phase of the study was able to accurately track deviations from home regimens and, more importantly, show that deviations in drug administration had impacts on outcomes:

“Our first-year findings, which will soon be published in Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, highlight the significant opportunities for improvement with new interventions,” Dr. Walter says. “Our goal is to define a proactive approach so that deviations from a patient’s medication regimen are consistently avoided before complications occur.”

The team has developed an inpatient PD consultation service, using advanced practice providers. Specific intervention goals include the following:

Advertisement

An electronic medical record tool was developed that includes a registry of patients admitted with PD so that the team can easily identify and promptly consult on these patients before problems develop. Drug-drug interactions are flagged by the tool, and medication order constraints are specified. “Custom orders” to choose precise times of drug administration are forced.

The new system will be evaluated for its impact on medication errors at six months and again at 12 months after a review and adaptive redesign. At the end of the study, the impact of reduced medication errors on patient outcomes will be examined.

“Additional inpatient Parkinson’s services add costs upfront, but they have the potential to reduce length of stay, cost of care and, most importantly, complications,” Dr. Walter observes. “We know medication errors in this population are a huge problem, and the benefits of avoiding them can be great.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Various AR approaches affect symptom frequency and duration differently

Dopamine agonist performs in patients with early stage and advanced disease

Early assessment could affect clinical decision making

Systems genetics approach sets stage for lab testing of simvastatin and other candidate drugs

Study aims to inform an enhanced approach to exercise as medicine

New tool for general neurologists aims to streamline differential diagnosis

When and how a multidisciplinary palliative care clinic can fill unmet needs for this population

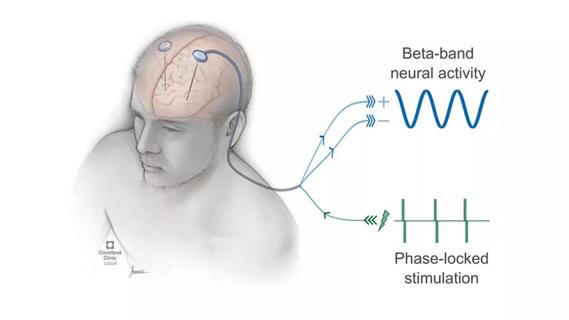

Research project will leverage insights into neural circuits to advance DBS technology