Series of 145 patients characterizes scope of presentations, interventions and outcomes

For patients with complications years after initial aortic coarctation repair, interventions are likely to be successful when tailored to individual anatomy and pathology. So concluded Cleveland Clinic researchers who analyzed nearly 25 years of data from patients who underwent late reintervention for complications of aortic coarctation repair, as reported in an online publication in JTCVS Techniques.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Addressing these varied late complications can be challenging, but reintervention with good results is feasible at a dedicated aorta center,” says senior author Eric Roselli, MD, Chief of Adult Cardiac Surgery and Director of the Aorta Center at Cleveland Clinic. “We employ a variety of techniques — including endovascular, open and hybrid approaches — depending on the patient’s anatomy and circumstances.”

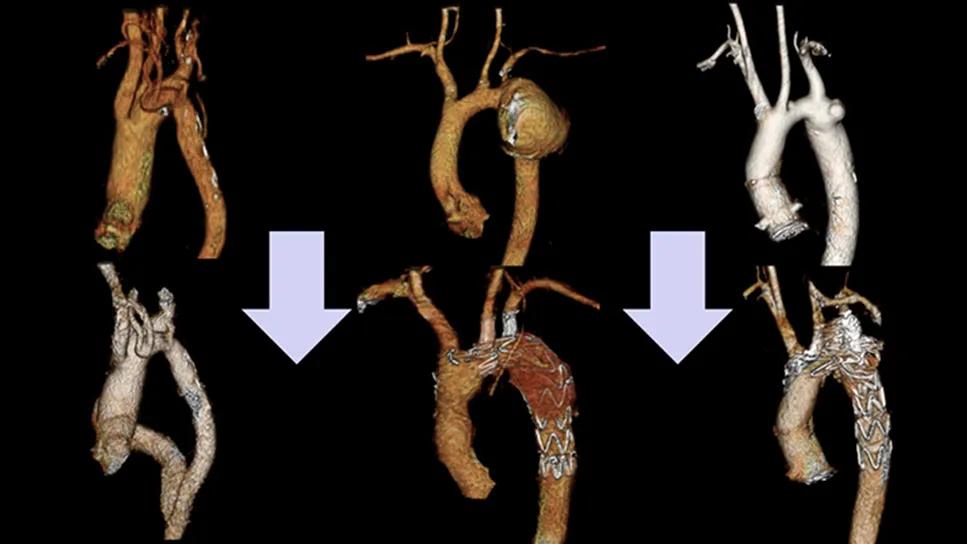

As infants and children who underwent aortic coarctation repair now commonly have long lifespans, increasing numbers of adults are developing late complications in the area of the treated segment. These include recoarctation (new narrowing of the aorta), aneurysms in adjacent segments of the aorta and pseudoaneurysms (bulging due to breakdown in the previous areas of repair).

Although often asymptomatic and insidious in development, these lesions can lead to dire cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, including stroke, aortic rupture and death.

The current report of Cleveland Clinic’s experience in this understudied population characterizes these late complications (usually decades after aortic coarctation repair), describes decision-making for the various reintervention approaches, and presents short- and long-term outcomes.

The study analyzed Cleveland Clinic medical records between 1999 and 2023 for patients who underwent reintervention for complications associated with an earlier aortic coarctation repair. Patients with pseudocoarctation or coarctation remote from the aortic isthmus were excluded. The cohort consisted of 145 patients (mean age, 38 ± 16 years; 66% male).

Advertisement

Patients had the following indications for reintervention:

Coexisting congenital lesions included bicuspid aortic valve (50%, n = 73), aortic arch variants and anomalies (23%, n = 33) and ventricular septal defect (10%, n = 15).

The most common presenting symptoms were shortness of breath (17%, n = 25) and chest pain (16%, n = 23), with smaller numbers having fatigue, leg weakness or pain, headache, back pain, chest tightness and dizziness. However, a large proportion of patients were asymptomatic (43%, n = 63), with the lesions found incidentally on imaging. Most patients (74%, n = 107) had hypertension.

“As reflected in the cohort, these patients can be incredibly complex,” notes study co-author Patrick Vargo, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon with the Aorta Center. “Fortunately, we have excellent multimodal imaging techniques at our disposal to thoroughly assess the situation, and there are many options for intervention, allowing us to design an optimal strategy precisely tailored for each patient.”

Advertisement

Reintervention took place a median of 29 years (15th-85th percentiles, 9-44 years) after the initial repair. Multiple strategies were used:

“In general, we prefer endovascular repair for managing reinterventions involving isolated lesions in patients with appropriate anatomy,” says Dr. Roselli. “However, we consider open or hybrid approaches for those with extremely narrow coarctation, tortuous aorta, suboptimal landing zones or coexisting cardiovascular lesions such as bicuspid aortic valve, ascending aortic aneurysm, ventricular septal defect or coronary artery disease.”

About a quarter of patients (26%, n = 37) had concomitant cardiovascular procedures performed during the repair, most commonly involving the aortic valve and/or proximal aorta.

Among patients who underwent recoarctation repair, technical success was achieved in all but two patients (72/74, 97.3%), both of whom had underexpanded bare metal stents, and the average peak trans-coarctation gradients fell from 29 to 3 mm Hg postoperatively.

Advertisement

Three patients (2.1%) died during reintervention, two from anoxic brain death and one from malperfusion syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation after open descending aortic repair.

Major adverse events included stroke in three patients (2.3%), acute kidney injury requiring dialysis in three patients (2.3%) and transient spinal cord injury in one patient (0.7%).

“Interestingly, spinal cord injury, which historically has been a feared complication associated with descending aorta replacement, occurred in just one patient, and it was transient,” Dr. Vargo notes. “We attribute this to improved techniques for spinal protection and the increasingly common use of endovascular approaches.”

Patients were followed for a median of 7.9 years following reintervention. Estimated outcomes at follow-up intervals were as follows:

“Patients with residual trans-coarctation gradients over 5 mm Hg were more likely to require late reintervention,” Dr. Roselli says. “We learned that near-total resolution of blood pressure gradient should be a high priority during repair.”

The authors note that after initial coarctation repair, regular blood pressure monitoring is essential since all patients with a history of coarctation are at risk for hypertension. They also recommend that all patients undergo periodic lifelong imaging surveillance after initial repair to detect asymptomatic pathology. After reintervention, Cleveland Clinic physicians conduct surveillance as follows:

Advertisement

“Patients with prior aortic coarctation repair should be educated about the importance of lifelong follow-up with a dedicated adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) specialist or an aorta specialist to allow for optimal blood pressure management and follow-up imaging such as echocardiography and CTA or MR angiography,” notes study co-author Vidyasagar Kalahasti, MD, a cardiologist with the Aorta Center. “This helps in identifying any recurrent complications, such as those outlined in this paper, so they can be treated accordingly at a high-volume center like Cleveland Clinic.”

“Patients with aortic coarctation, as well as other forms of congenital heart disease, benefit from long-term co-management by an ACHD specialist,” adds co-author Margaret Fuchs, MD, a clinical cardiologist specializing in ACHD. “As the study shows, a variety of aortic complications can arise, sometimes decades after initial repair, so serial screening is a requirement. For patients who develop an aortic complication requiring intervention, outcomes are best when the interventional and surgical teams have expertise in managing congenital aortic disease. An ACHD specialist can guide patients to the ideal intervention at the correct time, as well as manage other associated congenital heart conditions that commonly occur in coarctation patients.”

Image at top: Coarctation repair–associated lesions treated with aorto-aortic bypass, B-SAFER and a stent. Reprinted from Putnam et al., JTCVS Techniques (2025 Epub 14 Oct), under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

Advertisement

New Cleveland Clinic data challenge traditional size thresholds for surgical intervention

Experience-based takes on valve-sparing root replacement from two expert surgeons

Study finds comparable midterm safety outcomes, suggesting anatomy and surgeon preference should drive choice

New review distills insights and best practices from a high-volume center

JACC State-of-the-Art Review details current knowledge and new developments

When to recommend aortic root surgery in Marfan and other syndromes

Blood test can identify patients who need more frequent monitoring or earlier surgery to prevent dissection or rupture

Recent Cleveland Clinic experience reveals hundreds of cases with anatomic constraints to FEVAR