Advice on why and how based on Cleveland Clinic’s recent enterprise-wide transition

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8ad4dc14-a73d-4018-aa17-cb8f2d384929/22-NEU-2646461-thrombolysis-ischemic-stroke-650x450-1_jpg)

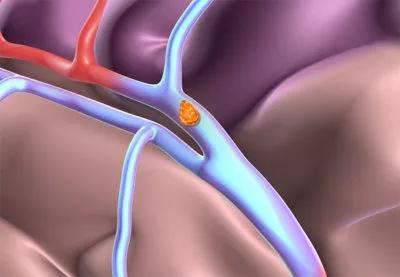

22-NEU-2646461-thrombolysis-ischemic-stroke-650×450

January 11, 2022, was “TNK Day” at Cleveland Clinic. At 10 a.m., across the entire health system, clinicians in every institute, department and emergency room who care for adults with acute ischemic stroke stopped using alteplase and started using tenecteplase (TNK) for thrombolysis within 4.5 hours of patients’ last known well time.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The change, which took nearly a year to plan and organize, was spurred by a growing body of evidence from clinical trials and clinical guidelines supporting TNK as an alternative to alteplase. It puts Cleveland Clinic among early adopters of TNK for acute stroke thrombolysis on an enterprise-wide basis.

“Our decision to switch was guided, in part, by multiyear experience from systems like Ascension Seton in Texas,” says Andrew Russman, DO, Head of Cleveland Clinic’s Stroke Program and Medical Director of its Comprehensive Stroke Center, who championed the effort. “The timing gave us the benefit of both clinical trial data and real-world safety and efficacy data, with a number of health systems presenting their TNK data at the International Stroke Conference in 2021.”

TNK was FDA-approved to reduce mortality in acute myocardial infarction in 2000. In the ensuing two decades, in randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses, the bioengineered tissue plasminogen activator has been proven to have noninferior safety and efficacy compared with alteplase in acute ischemic stroke — and a potential advantage in early recanalization.

“In the EXTEND-IA TNK trial, early reperfusion was achieved in 22% of patients who received TNK versus 10% of those who received alteplase,” says Dr. Russman. “With TNK, there is a better chance than with alteplase that a patient’s vessel will already be open before they get to the angiography suite.”

TNK also offers easier administration. It is given as a single IV bolus (0.25 mg/kg; maximum 25 mg) over 5 seconds, whereas alteplase requires 10% of the weight-based dose to be given by bolus followed by an IV infusion of the remaining 90% over 60 minutes.

Advertisement

“The time it takes to depress the plunger on the syringe is how long it takes to give TNK,” says Dr. Russman. “Unlike with alteplase, there is no tubing to hook up, remove and flush. Administration is less nursing- and resource-intensive, although post-treatment monitoring is the same.”

To prepare for replacing alteplase with TNK as the preferred enterprise-wide thrombolytic for acute ischemic stroke in adults, Cleveland Clinic stroke leaders were empowered to champion TNK. Education about the change and how to incorporate it into workflows was provided to all caregivers involved in the care of stroke patients.

The key logistical challenge to overcome was drug packaging. “The TNK box is labeled with dosing information for myocardial infarction, not stroke,” Dr. Russman explains. “Our pharmacy leadership team decided to remove the drug from the box and put it into a Cleveland Clinic-labeled kit. This kit includes a 50-mg vial of the drug, a 10-mL vial of sterile water for injection and a drug dosing card for both myocardial infarction and stroke.”

Currently, TNK is only given to patients from 0 to 4.5 hours after onset of ischemic stroke symptoms. That may change, however, if data from clinical trials on an extended window or use in other populations are positive. The phase 3 Tenecteplase in Wake-up Ischaemic Stroke Trial (TWIST) is comparing TNK 0.25 mg/kg versus standard care in patients within 4.5 hours of awakening. Cleveland Clinic is participating in TIMELESS (Tenecteplase in Stroke Patients Between 4.5 and 24 Hours), a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the same TNK dosage in patients with large vessel occlusion.

Advertisement

“Patients with stroke symptoms beyond 4.5 hours from onset traditionally have not been candidates for IV thrombolysis,” Dr. Russman observes. “TWIST is looking at that, with results expected in May. We eagerly await the data from TWIST and TIMELESS to see if other populations can benefit from IV TNK.”

In the first two weeks after January 11, about 20 patients with acute ischemic stroke were treated with TNK at Cleveland Clinic. Routine clinical data on experience with the drug will be analyzed to determine its impact. Metrics to be studied include clinical outcome, time to treatment, rates of recanalization of the target artery and incidence of complications such as intracranial hemorrhage.

Dr. Russman advises others thinking about switching to TNK to move prudently, but not to hesitate. “Many U.S. stroke neurologists believe there is no longer equipoise about whether TNK is as good as alteplase in the first 4.5 hours after symptoms onset,” he says. “The data appear sufficient to justify a change.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient