Hospital improves access to pumps, saves time and money

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8760abf9-71ac-4ecd-9297-a9ef621e99df/CCC_3561108_1-23-23_359_MLC-jpg)

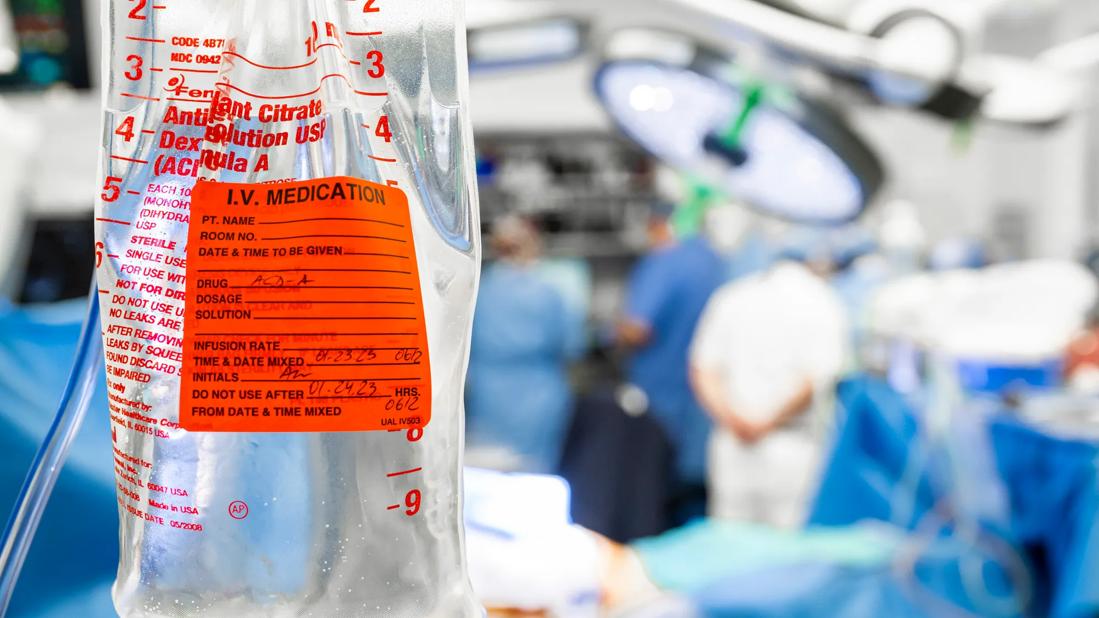

IV medication

In 2018, a team of nurses at Cleveland Clinic Medina Hospital working on an “ED to Bed” project identified several barriers that extended the time from the disposition decision to hospital admission. One of the factors that slowed patient transfers to a nursing unit was lack of IV pumps.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Danielle Razavi, BSN, RN, who served as assistant nurse manager of the Emergency Department at the time, launched a multidisciplinary continuous improvement (CI) project in early 2019 to investigate and improve the IV pump management process. “When we really looked at IV pump asset management, we realized it affected a lot more than nursing and patient care,” says Razavi, now nurse manager of the ICU. “The Sterile Processing Department and Clinical Engineering were also having issues.”

Razavi and her peers kicked off the CI project with an “IV Pump Seek and Find” day. “We wanted to determine if the root problem was that we don’t have as many IV pumps as we think we do,” says Ed Leichliter, BSN, RN, assistant nurse manager of the step-down unit. “The team spread out on every floor of the hospital at the same time. We looked in patient rooms, utility closets, hallways – everywhere – to get an exact count of our pumps.”

The team found 172 IV pumps, a figure suitable for Medina Hospital, which has 148 beds on eight nursing units. Armed with that information, the CI team created a process map to track how pumps move from the Sterile Processing Department (SPD) to nursing units and back again, with stops in Clinical Engineering if they are defective. Team members also talked to clinical nurses and staff in SPD and Clinical Engineering to ask their opinions on flaws in the process.

One primary complaint was that nurses, patient care nursing assistants and health unit coordinators were spending a lot of time searching for IV pumps. So the CI team asked nursing staff to log the exact amount of time they spent looking for IV pumps for two weeks. The log revealed that 140 nursing minutes were squandered each week hunting for pumps.

Advertisement

“Nurses were spending a lot of time searching for pumps, which is frustrating for them,” says Leichliter. “In addition, if patients aren’t getting medications in a timely manner, it can prolong their stay in the hospital.”

In addition to a lack of clean pumps on nursing units, the CI team identified these other problems with the IV pump management process:

Improper cleaning of pumps by nurses after usage

The CI team came up with strategies to streamline the IV pump management process. First, they made space in each unit for a clean and soiled utility room to store pumps. The team took photos of each room to show nurses that they should look like and how to properly store pumps. In addition, they added an IV pole with a multi-plug electrical outlet to each utility room so the batteries aren’t drained during storage. “There is a specified place to put pumps rather than setting them on a counter unplugged and balling up cables,” says Leichliter.

In addition, members of the CI team talked with SPD about changing the times they deliver clean pumps to units and pick up dirty ones to better coincide with patient admissions and discharges. They also worked with Clinical Engineering to create a defective tag for malfunctioning pumps. “When nurses have a problem with a broken pump, they list the exact problem on the tag and place it in the soiled utility closet,” says Razavi. “This helps Clinical Engineering fix the pump more quickly and get it back in circulation rather than going through all the possible problems.”

Advertisement

Finally, the CI team established minimum IV pump stocking levels on each unit and updated the IV pump management procedures. Then, they educated staff on the new process during huddles and rounded on the units to ensure the procedure was being followed. “We explained to nurses that if they trusted the process it would work,” says Leichliter. “It took some buy-in.” Assistant nurse managers also rounded to make sure pumps were placed in the soiled utility room after patient discharge.

The project was a resounding success, increasing efficiency and saving the hospital time and money. When the CI team began its analysis in January 2019, SPD cleaned just over 200 pumps that month. In September 2019, the department cleaned and returned 800 pumps to circulation. In addition, by reducing the time for SPD to pick up and distribute pumps by 45 minutes each day and eliminating the 140 minutes per week nursing staff spent searching for pumps, Medina Hospital saved a total of 391 annual labor hours totaling more than $8,500 in savings.

An added benefit is the camaraderie the project created among disciplines. “It helped our relationships with other departments,” says Razavi. “Once we resolved the IV pump issues, it made our interactions much better.”

Having enough pumps in circulation has also been tremendously helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Having this project done prior to the pandemic was a blessing in disguise,” says Leichliter. “With everybody trusting in the process and trusting one another, it’s allowed pumps to be distributed to units properly. To continue to do that and not have units short on IV pumps during the pandemic has been awesome.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Regional organizations collaborate to address nurse faculty shortage

How wellness habits help nurses flourish

Planning continues with critical, patient-focused input from nursing teams

Strengthening care through targeted resources and frontline voices

Embracing generational differences to create strong nursing teams

CRNA careers offer challenge and reward

An unexpected health scare provides a potent reminder of what patients need most from their caregivers

Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi initiative reduces ICU admissions and strengthens caregiver collaboration