Indications and best-practice recommendations for the use of androgen therapy

By Taryn Smith, MD, NCMP, and Pelin Batur, MD, FACP, NCMP

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Please note: This is an abridged version of an article recently published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. To read it in its entirety, including a complete set of references, please visit: https://www.ccjm.org/content/88/1/35

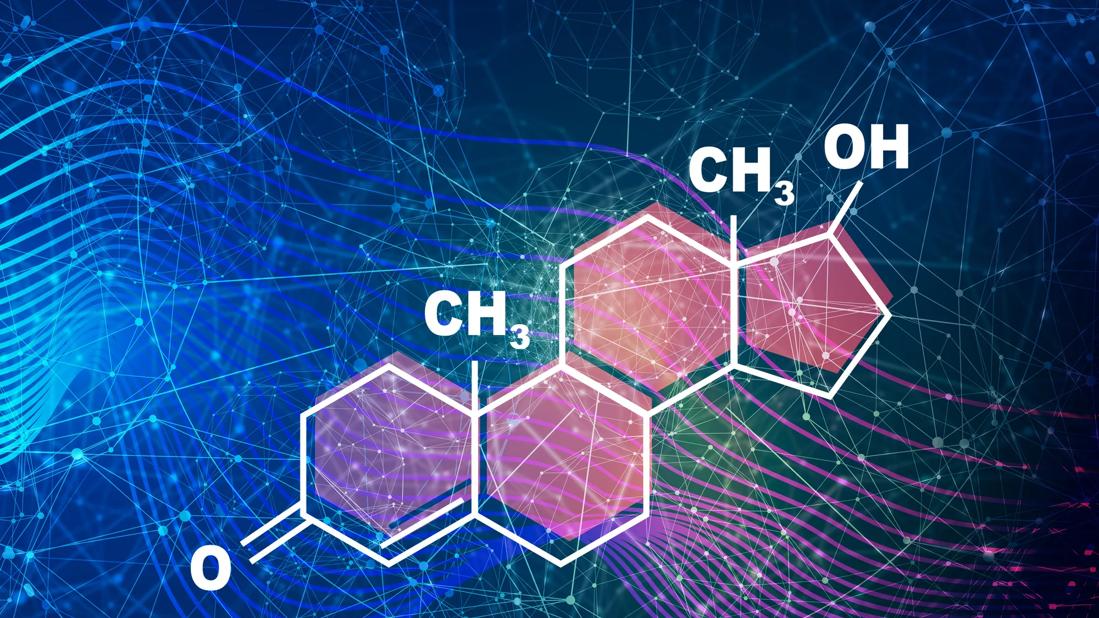

Estrogens are the principal sex hormones responsible for female reproductive maturation and sexual characteristics. However, androgens are also important for female sexual health and well-being.1 The physiologic effects of androgens are in part due to their role as precursors for estrogen synthesis, but these hormones also have independent effects on female reproductive tissues, mood, cognition, breasts, bones, muscles, vasculature and other systems.1

Currently, the only evidenced-based indication for testosterone therapy in women is for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. Several randomized controlled trials have established the short-term safety and efficacy of prescribed testosterone in women when doses approximate physiologic levels. Here we will discuss the physiologic roles of androgens as well as the indications and best-practice recommendations for androgen therapy in women.

The biologically active androgens in women are dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), androstenedione, testosterone and dihydrotestosterone.

In women, roughly 25% of androgen production occurs in the adrenal glands, 25% occurs in the ovaries, and the rest occurs peripherally.2 DHEA-S, DHEA and androstenedione are the main prohormones that are peripherally converted to the active androgens testosterone and dihydrotestosterone. DHEA-S is almost exclusively produced in the adrenal glands, whereas DHEA, androstenedione and testosterone are produced in the adrenal glands and ovaries and by peripheral conversion. In target tissues, circulating testosterone is converted to dihydrotestosterone by 5-alpha-reductase and aromatized to estradiol.

Advertisement

Androgen levels decline with age throughout a woman’s life, starting in her mid-30s.3 Menopause is not associated with a rapid decline in androgen production; the postmenopausal ovary is hormonally active and accounts for 40% to 50% of postmenopausal testosterone production.4,5 Consequently, women who have undergone bilateral oophorectomy have a marked decrease in circulating testosterone levels, though serum concentrations of DHEA and androstenedione remain stable due to adrenal compensation.4 Ten years after the onset of menopause, circulating testosterone and androstenedione levels are half of perimenopausal levels.6

In circulation, active testosterone is free or bound to albumin. Testing of total testosterone levels also measures inactive testosterone, which is bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), a liver-synthesized protein with a high affinity for sex steroids. Conditions that increase (e.g., pregnancy, exogenous estrogen therapy, liver cirrhosis, hyperthyroidism) or decrease (i.e., obesity, exogenous androgen therapy, insulin, glucocorticoids) SHBG inversely affect circulating levels of free (active) testosterone.

Symptoms of “female androgen insufficiency” have been popularly described as including sexual dysfunction, chronic fatigue, dysphoric mood and diminished sense of well-being. However, low serum androgen levels do not reliably correlate with a clinically defined syndrome. Even among oophorectomized women, a decline in serum testosterone level does not consistently correlate with clinical symptoms.27 Lack of congruency among current laboratory assays also limits the development of biochemical criteria to diagnose androgen insufficiency in women.

Advertisement

For these and other reasons, the Endocrine Society recommends against diagnosing “female androgen deficiency” or using testosterone to treat low androgen states in women.28 There is no evidence to support testosterone therapy for female well-being, mood, vasomotor symptoms, bone health, cardiovascular health or metabolic dysfunction.8,27,29

It is important to remember that numerous medical conditions and medications can result in low androgen levels in women, including chemotherapy, radiation, ovarian insufficiency, adrenal insufficiency, malnutrition, hormonal contraceptives, corticosteroids, antiandrogenic agents, oral estrogen therapy and opioids.

Despite studies showing potential benefits in sexual health, no testosterone formulations for women have been approved for use in the United States for this indication. Short-term low-dose transdermal formulations are the preferred method of testosterone delivery for women, based on available safety data and side effect profiles. The twice-weekly 300-μg/day patch was previously approved in Europe; however, it is no longer available due to low sales.27 This product was never approved in the United States.

Testosterone formulations available in the United States are indicated for use in men only, and clinicians should use caution when prescribing them to women. To avoid supraphysiologic dosing, women should be prescribed a tenth of the recommend male dose—or less. However, even when only 1 month’s worth of a male product is prescribed, a patient will have a year’s supply of medication, which increases the risk for supraphysiologic dosing if she applies the product more than recommended, and does not return to be assessed for safe blood levels. Compounded formulations are frequently used for women; however, these products are not subject to potency and purity regulations.

Advertisement

Topical products should be applied to the inner thigh, buttock, abdomen or vulva to avoid transfer to contacts. The breast and arms should be avoided. We recommend use in an area that can be shaved in case of increase in hair growth. Adverse events are limited when serum testosterone levels remain in physiologic ranges.

Oral testosterone undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver and tends to be associated with more side effects and adverse events than other formulations.13,14 For this reason, the most recent consensus statement discourages the use of oral testosterone.8

Oral combination esterified estrogenmethyltestosterone (EEMT) has been on the market since the 1960s. It was approved by the FDA on the basis of its safety before the current safety and efficacy requirements were enacted. The manufacturers have not sought reapproval. Oral EEMT is indicated for use in postmenopausal women with moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms not improved on estrogen alone. Two doses are available (estrogen 1.25 mg plus methyltestosterone 2.5 mg, and estrogen 0.625 mg plus methyltestosterone 1.25 mg), and short-term use is recommended. A 2003 postmarketing safety surveillance study revealed very few serious adverse events in women using EEMT between 1989 and 2002.47

If oral therapy is chosen, cardiometabolic risks should be assessed at follow-up visits. In addition, liver function tests should be monitored periodically.

Intramuscular and pellet therapies should be avoided. These options expose users to potential for prolonged exposure and supraphysiologic dosing.8

Advertisement

Once a decision to start systemic testosterone has been made, the Endocrine Society and the Global consensus position statement on the use of testosterone therapy for women recommend checking baseline testosterone levels before initiating therapy.7,8,28 Levels should then be followed 3 to 6 weeks after therapy is initiated and every 6 months thereafter to avoid toxicity and supraphysiologic dosing.28 Serum hormone levels do not correlate with clinical response, and measuring them is intended to ensure safe delivery of treatment. In contrast, women using vaginal DHEA should not have blood hormone levels checked, as the serum concentration of sex steroids is minimally affected by this route of administration.

The follow-up should focus on a clinical assessment of perceived risks vs benefits. The goals are to improve sexual desire, arousal, orgasmic function, pleasure or sexual responsiveness, with a reduction in sexual concerns and distress. The treatment should be stopped in women who do not respond to therapy after 6 months of consistent use.

When hormone levels on treatment approximate the normal physiologic levels of a premenopausal woman, there is no significant increased risk of alopecia, clitoromegaly or voice changes.8,28 However, these potential concerns should be reviewed with patients. Mild increases in acne or hirsutism may be seen. The risk of vaginal bleeding was increased in the users of the 300-μg/day patch, though no increased risk of endometrial hypertrophy was observed over 12 months.28 Any woman with postmenopausal bleeding should undergo endometrial assessment, whether or not she is using hormonal therapies.

There is no indication to perform additional breast imaging, cardiac testing or other laboratory tests. However, patients should be seen at least annually in clinic to ensure they are up-to-date with their preventive screenings. When serum testosterone levels remain in normal physiologic ranges, studies show that neither oral nor nonoral testosterone therapy significantly affects the lipid profile, glycemic markers, blood pressure, body mass index or hematocrit.7,13 No current evidence links physiologic-dose testosterone therapy with adverse cardiovascular events, though most studies followed patients for less than 5 years and excluded those considered at high risk for cardiovascular disease and breast cancer.8,9,11A recent meta-analysis showed that testosterone therapy was not associated with more serious adverse events than placebo or a comparator.12

For a complete list of references, please visit https://www.ccjm.org/content/88/1/35.

Advertisement

Uterine transposition cleared the field for radiation therapy

ACOG-informed guidance considers mothers and babies

Prolapse surgery need not automatically mean hysterectomy

Artesunate ointment shows promise as a non-surgical alternative

New guidelines update recommendations

Two blood tests improve risk in assessment after ovarian ultrasound

Recent research underscores association between BV and sexual activity

Psychological care can be a crucial component of medical treatment