Most substantial reversal of amyloid deposition in an animal study to date

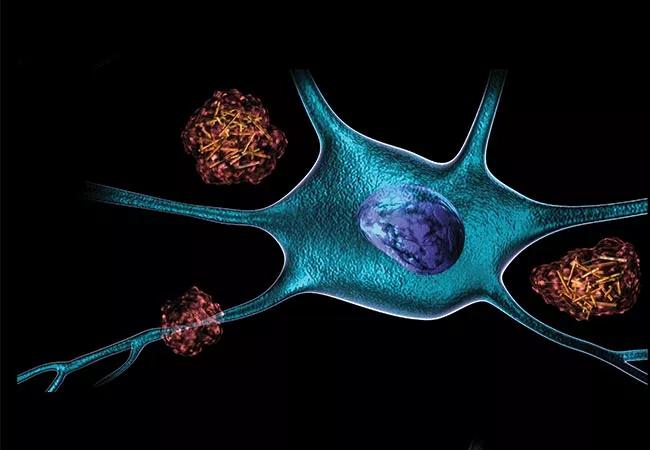

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e2b08fd2-e804-417f-8353-e3fc91372c83/18-NEU-687-Yan-650x450_jpg)

18-NEU-687 Yan-650×450

Researchers from Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Neurosciences have demonstrated that depleting the BACE1 enzyme in middle-aged mice with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) fully reverses formation of brain amyloid plaques and improves the animals’ cognitive function.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“To our knowledge, this is the first observation of such a dramatic reversal of amyloid deposition in any study of Alzheimer’s disease mouse models,” says lead researcher Riqiang Yan, PhD, Vice Chair of Neurosciences in Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute.

The findings, published Feb. 14 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, are seen as giving renewed support to the prospects of the BACE1 inhibitor class of experimental therapeutics for AD in humans, several of which have seen their clinical development discontinued in recent years.

BACE1, also known as beta-secretase, cleaves amyloid precursor protein, which promotes production of beta-amyloid peptide. The resulting buildup of beta-amyloid peptide has been implicated in the development of AD, which prompted the development of drugs that inhibit BACE1 for potential treatment of AD.

Yet because BACE1 has effects beyond the cleaving of amyloid precursor protein, inhibition of BACE1 could pose significant side effects. For instance, mice without any BACE1 are subject to severe neurodevelopmental defects.

So Dr. Yan and his Cleveland Clinic colleagues genetically engineered mice to gradually lose BACE1 as they age. The mice showed normal and healthy development over time.

The investigators then bred these mice with separate mice engineered to begin developing amyloid plaque — and thus AD — at 75 days of age. The offspring also began to show amyloid plaque formation at 75 days of age, but their levels of BACE1 were about half the level in normal mice.

Advertisement

Yet as the offspring mice aged further and lost BACE1 activity, they likewise underwent loss of previously formed amyloid plaques in their brains. By age 10 months — roughly the equivalent of age 50 years in humans — these mice had no brain amyloid plaque remaining.

“Sequential deletion of BACE1 not only slowed or halted the formation of amyloid plaques; it actually reversed existing plaques,” observes Dr. Yan. “This finding surprised us.”

Reduced BACE1 levels in the offspring mice also reversed other AD hallmarks, such as microglial cell activation and formation of abnormal neuronal processes. Moreover, reduced BACE1 was associated with improved learning and memory in the mice.

However, electrophysiologic recordings of neurons from these mice showed that BACE1 depletion restored synaptic function only partially. This finding, the researchers note, suggests that BACE1 may be necessary for ideal synaptic activity and cognitive function.

“This study provides genetic evidence that preformed amyloid deposition can be completely reversed after sequential and increased deletion of BACE1 in the adult mouse,” says Dr. Yan. “These data suggest that BACE1 inhibitors may hold the potential to treat AD in humans without unwanted toxicity.” He adds that future studies should explore strategies for minimizing synaptic impairments that appear to arise from significant BACE1 inhibition.

These findings come on the heels of the failure of several BACE1 inhibitors in clinical trials, although five such drugs are still in clinical testing. Dr. Yan speculates that some of the earlier failures may be attributable to use of the agents too late in the AD process.

Advertisement

“Our findings suggest that inhibiting BACE1 may have the greatest impact relatively early in the disease process,” he says. He notes that if BACE1 inhibition is ultimately demonstrated to be safe, BACE1 inhibitors might optimally be taken on a preventative basis for individuals at risk of AD.

The several ongoing trials of BACE1 inhibitors address various stages of AD, including presymptomatic stages, notes James Leverenz, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Cleveland. “We are excited to see the findings from Dr. Yan’s group and are keeping our fingers crossed that these results in mice will translate to the human disease,” says Dr. Leverenz.

Advertisement

Advertisement

First full characterization of kidney microbiome unlocks potential to prevent kidney stones

Researchers identify potential path to retaining chemo sensitivity

Large-scale joint study links elevated TMAO blood levels and chronic kidney disease risk over time

Investigators are developing a deep learning model to predict health outcomes in ICUs.

Preclinical work promises large-scale data with minimal bias to inform development of clinical tests

Cleveland Clinic researchers pursue answers on basic science and clinical fronts

Study suggests sex-specific pathways show potential for sex-specific therapeutic approaches

Cleveland Clinic launches Quantum Innovation Catalyzer Program to help start-up companies access advanced research technology