The cultural and technical factors promoting repair durability and a mortality-free stretch of 4,000+ cases

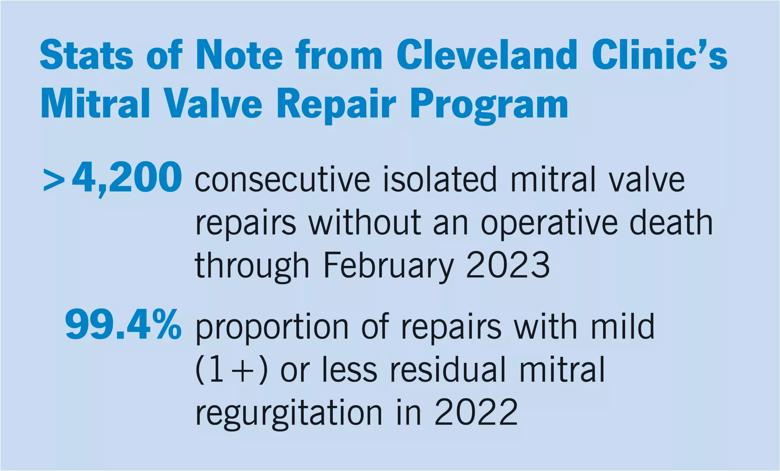

Earlier this year, Cleveland Clinic completed its 4,000th consecutive isolated mitral valve repair without a perioperative death, continuing a mortality-free stretch that dates back to 2014.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

While isolated mitral valve repair has come to be a relatively low-risk operation at most centers, the mortality rate nationwide remains near 1%, or 1 in 100 cases. In that context, the Cleveland Clinic rate of zero mortality across several thousand cases is of a different order of magnitude.

Consult QD caught up with several members of Cleveland Clinic’s mitral valve repair team to identify key factors, recapped below, that have contributed to this remarkable series of mortality-free operations and related success in the durability of mitral valve repairs.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/273cd818-9f95-44b3-8130-b1f5d4181597/23-HVI-3691658-CQD-Inset-scaled_jpg)

“Mitral valve repair is a very specialized operation, and it requires a great deal of experience to become competent and then excellent at it,” says A. Marc Gillinov, MD, Chair of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “We perform well over 1,000 mitral valve operations per year, and that sort of experience leads to excellence.”

“Our annual volumes of isolated mitral valve repair are the highest in the country, so there is virtually nothing we haven’t seen before,” says Daniel Burns, MD, MPhil, staff surgeon and Assistant Professor of Surgery in the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

“This depth of experience goes back some 35 or 40 years to when Toby Cosgrove, MD, helped pioneer many modern mitral valve repair practices here beginning in the 1980s,” notes Brian Griffin, MD, Medical Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Mitral and Tricuspid Valve Center. “From the start we have approached mitral valve repair with the view of continually learning as we go. From real-time imaging during repairs we have learned a lot about the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that can make a repair look adequate to a surgeon intraoperatively when in fact it might not be adequate in a beating heart. One example is systolic anterior motion, which our surgeons have since developed ways to predict and deal with.”

Advertisement

Experience hones not only technical skill but also judgment. “Judgment is essential to our results, from knowing in whom to operate and which approach can be used most safely, to knowing how to achieve an excellent repair with a relatively short operation so that the patient’s physiology is not stressed,” Dr. Gillinov observes.

Such judgment has resulted in a rate of repair (versus replacement) of well over 99% for isolated degenerative mitral valve disease at Cleveland Clinic in recent years. It also guides the choice among robotically assisted mitral valve repair, other minimally invasive approaches, and partial or full sternotomy.

“Patients often come to Cleveland Clinic asking specifically for a robotically assisted repair, but not all of them are good candidates,” says Dr. Burns. “Our job, regardless of what people are looking for, is to evaluate all facets of their presentation and then decide which operation is best for their individual situation. The priority determinant is whether a given operation will enable the valve to be repaired — and, specifically, be repaired safely. All other considerations come after that, including minimizing invasiveness, which we are readily prepared to do whenever it is safe.”

For example, a patient with low-risk anatomical features is likely to be a good candidate for a robotically assisted operation, whereas a full sternotomy is usually best for a patient with suboptimal heart function or with challenging body habitus, to ensure maximum visualization and safety. Partial sternotomy may be an ideal intermediate option for a patient who has one or two factors that rule out a robotic approach, such as poor suitability to peripheral cannulation, but who wants to avoid the longer recovery and larger scar associated with full sternotomy.

Advertisement

The team’s judgment in choice of operation is guided by a Cleveland Clinic-developed screening algorithm used to assess patients’ candidacy for a robotic procedure when undergoing repair for isolated degenerative mitral valve disease. The data-driven algorithm bases patient selection for robotic surgery on various features from transthoracic echocardiographic and CT evaluation, as well as established contraindications to robotic mitral valve surgery.

A recent study published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2022;164[4]:1080-1087) evaluated use of the algorithm across a 1,000-patient sample. It showed that 60% of screened patients qualified for robotic surgery and that these patients’ postoperative outcomes were just as good as those of patients undergoing mitral valve repair with sternotomy. “These findings validate this screening approach,” Dr. Gillinov notes.

“We have done a good job adhering to this algorithm rather closely,” Dr. Burns adds. “I think that has been a contributor to Cleveland Clinic’s zero mortality for mitral valve repair over many years and our very high repair rate.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7043cec7-ce27-4078-8aa3-7f82072647e8/23-HVI-3691658_robotic-surgery_jpg)

Photo of a robotically assisted mitral valve repair operation. Cleveland Clinic uses a homegrown screening algorithm to assess whether patients are good candidates for robotically assisted mitral valve repair. A recent study showed that 60% of screened patients qualified for robotic repair and that these patients’ outcomes were as good as those of patients undergoing sternotomy.

Advertisement

The Cleveland Clinic mitral valve surgery team describes their screening algorithm for robotic procedures as “conservative” — without apology. “It is our philosophy that minimally invasive surgery is only appropriate when it can be offered without sacrificing safety or quality,” they wrote in a recent commentary in JTCVS Techniques (2021;10[C]:82-83).

The team elaborated further in another recent paper, “The 10 Commandments for Mitral Valve Repair” (Innovations [Phila]. 2020;15[1]:4-10), writing: “Surgeons may opt to ‘push the envelope’ and tackle a complex valve with a less invasive approach. This is a mistake and can result in extended cross-clamp times, limb ischemia (in the case of femoral perfusion), and adverse outcomes.”

Beyond its priority role in choice of operative approach, safety is fundamental to other aspects of the Cleveland Clinic team’s success. For instance, an insistence on preoperative CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis before robotically assisted repairs helps ensure safe and effective femoral perfusion. “After instituting routine CT scanning for patients undergoing robotic mitral valve repair, we cut our stroke rate by more than half,” Dr. Gillinov notes. “For borderline vessels, we expose the femoral vessels before chest incision and port placement. In rare instances, we may switch to sternotomy on that basis.”

As a former Cleveland Clinic advanced robotic and minimally invasive surgery fellow who joined the professional staff in 2018, Dr. Burns has firsthand knowledge of the depth and value of Cleveland Clinic’s mitral valve surgery expertise. “Our large volumes have allowed us to develop a team of multiple surgeons who are mitral valve experts,” he says. “We often operate with two highly experienced surgeons together, particularly if it’s a complex case, to ensure that every patient gets an exemplary repair.”

Advertisement

As intraoperative echo has assumed an increasingly important role in mitral valve repairs, partnership with the echocardiographer looms large as well. “Teamwork between the surgeons and the echocardiographer, typically a cardiothoracic anesthesiologist, is critical,” Dr. Gillinov observes. “Without an expert doing the echocardiogram, excellent mitral valve repair would be extremely challenging.”

Dr. Burns concurs. “We rely heavily on intraoperative transesophageal echocardiograms from our anesthesiology colleagues,” he says. “They do a masterful job of initially pinpointing the valve pathology to precisely guide our repair with the maximum amount of information. Their images are exceptional — it’s almost like viewing the valve with our own eyes. Then, after we repair the valve, the same expert imagers are there in the operating room to do another echocardiogram to thoroughly assess the valve and confirm the repair quality.”

The importance of teamwork to mortality success continues in the postoperative setting, with support from intensivists, advanced practice providers and surgical trainees, “who are always available as first responders when issues arise,” Dr. Burns notes.

While operative survival is an obvious prerequisite for all other outcomes, good valve function over the long term is the reason patients undergo mitral valve repair in the first place.

“Twenty-five to 30 years ago, we thought these repairs would last an average of 10 to 15 years,” says Dr. Griffin. “Now we find that at 20 years there’s about a 10% risk of needing a reoperation, so it’s a much more durable procedure than we ever thought.”

He attributes the greater repair durability to a number of insights and advancements over the years, including routine placement of a prosthetic annuloplasty ring or band to reduce the size of the mitral annulus, which enlarges over time as a result of regurgitation. “This appears to be important for long-term valve durability,” Dr. Griffin notes. “Additionally, it seems that repair surgery may do more than just correct the regurgitation but perhaps also changes some biomechanical forces so that the valve essentially resets itself for a long period.”

Regardless of mechanisms, “a good long-term result is predicated on an excellent short-term result,” says Dr. Gillinov. “That means having the very highest standards in the operating room to get the repair as close to perfect as humanly possible,” with perfect defined as zero or close to zero mitral regurgitation.

This is where teamwork with the echocardiographer — to meticulously inspect the repair before the incision is closed — is most important. “Our expert imagers confirm whether the repair looks perfect,” Dr. Burns says. “If it looks anything but perfect, they help us understand the precise source of any residual regurgitation. We can then have a well-informed discussion about whether to do a second bypass pump run and revise the repair — and, if so, exactly what pathology we’re going after. We are aggressive about fixing repairs in this context, so it’s rare that we have more than trace residual mitral regurgitation when we leave the operating room. This ensures a remarkable success rate for repair quality.”

“Later, typically before the patient is discharged home, we perform another echocardiogram to ensure there has been no slippage,” Dr. Griffin adds.

“There is increasing evidence that small differences in the degree of residual mitral regurgitation — even mild versus none or moderate versus mild — result in long-term functional differences and potentially in long-term survival differences,” Dr. Burns says. “The implications for patients can be substantial.”

Advertisement

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Two surgeons share insights on weighing considerations across the lifespan

An overview of growth in robot-assisted surgery, impressive re-repair success rates and more

Judicious application yields a 99.7% repair rate and 0.04% mortality

Cleveland Clinic series supports re-repair as a favored option regardless of failure timing

A call for surgical guidelines to adopt sex-specific thresholds of LV size and function