Case study illustrates the potential of a dual-subspecialist approach

When a previously healthy woman developed a bowel obstruction in her hometown of Fort Wayne, Indiana, no one anticipated it would lead to a life-threatening airway injury. After over a month intubated and delayed tracheostomy, the patient arrived at Cleveland Clinic with severe tracheal stenosis. An approach spearheaded by two fellowship-trained laryngologists restored her airway — and her voice.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

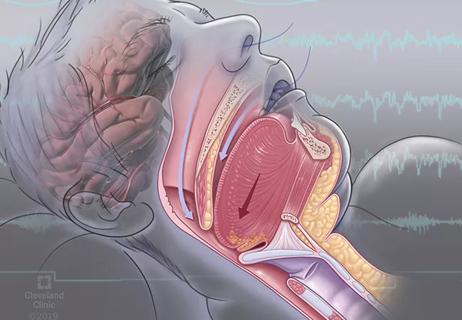

“This was a patient who had no connection between her lungs and vocal cords,” says William Tierney, MD, a laryngologist in the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “She was breathing entirely through a tracheostomy, with a completely obstructed upper airway. That’s where we came in.”

The patient had suffered a prolonged (> 14 day) intubation for over a month prior to her tracheostomy in Indiana. Her airway was injured by the pressure of the endotracheal tube cuff and subsequently developed Grade 4 (>99%) tracheal stenosis, precluding voicing, breathing through mouth or nose, and completely changed her life.

This case not only illustrates the technical demands of tracheal resection but also reinforces the critical importance of early tracheostomy and airway surveillance in patients requiring prolonged intubation.

The patient, an active woman with no significant medical history, developed a bowel obstruction and presented to a local emergency department. She began vomiting and received a nasogastric tube to evacuate her stomach. Believing the obstruction had resolved, the care team removed the NG tube and gave her oral contrast for a CT scan.

“While she was in the CT scanner, it became clear that the obstruction hadn’t resolved. She vomited, aspirated on the contrast and developed pneumonitis — a potentially life-threatening complication,” Dr. Tierney says. “She ended up requiring intubation and then eventually extracorporeal mechanical oxygenation, or ECMO. She was intubated for over 30 days without tracheostomy. They delayed a tracheostomy because they didn’t think she would survive.”

Advertisement

A tracheostomy was eventually placed, and she was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. However, she soon noticed she was losing the ability to speak. By the time she was referred to Cleveland Clinic, she could no longer vocalize and had no patent airway above the tracheostomy. “She essentially had a completely occluded upper airway,” Dr. Tierney says. “Grade 4 tracheal stenosis — meaning 99% or greater obstruction.”

Bronchoscopy confirmed the severity of the stenosis and revealed that no airflow passed through the mouth or nose. The obstruction was composed of dense scar tissue where her tracheostomy had been placed and remained for an extended period.

“This is the most severe presentation we see with airway stenosis,” says Dr. Tierney. “It’s rare, but unfortunately, we’re seeing more of these cases since COVID-19, when prolonged intubation became more common and airway protocols were often not followed.”

With the diagnosis confirmed, the team at Cleveland Clinic developed a surgical plan: tracheal resection. The surgery was performed by Dr. Tierney and his colleague, Rebecca Nelson, MD. Together, the laryngologists brought complementary training and techniques to the procedure.

“We’re one of the only programs in the country where two subspecialist laryngologists perform these resections together,” he explains. “It gives us different perspectives and toolsets for solving complex airway problems.”

The procedure began with excision of the infected and scarred tracheostomy tract. The surgical team then skeletonized the laryngotracheal framework to expose the site of the stenosis. “You can often see an hourglass effect where the trachea has been pulled inward by scar tissue,” Dr. Tierney notes.

Advertisement

After completely removing the stenotic segment, a breathing tube was placed into the distal trachea. This is followed by mobilizing the tracheobronchial tree, according to Dr. Tierney. “We then sutured everything back together, removing the breathing tube at the end.”

As the patient woke up from surgery, her care team witnessed a powerful moment. “Her very first words in the OR were, ‘Thank you,’” Dr. Tierney recalls. “That gives you a sense of who she is. She’s just a lovely person. Her focus is on the people around her, even when sedated and recovering from a major surgery.”

Overall, her recovery was uneventful. Within weeks, she was breathing and speaking normally. She returned to the OR to trim the suture and confirm that the surgery was a success. By eight months post-op, she is back to running on a treadmill with her husband and describes her life as “completely back to normal.”

Dr. Tierney notes that while most patients with airway stenosis require multiple surgeries, she had far fewer. “The average person who ends up with airway stenosis typically has five to eight surgeries to manage it, and she only needed two [at the Cleveland Clinic], which is dramatically better,” he says.

Cleveland Clinic’s recovery protocol for tracheal resection includes five to seven days of inpatient stay, local follow-up through the second week, and a surveillance bronchoscopy at four to six weeks. Patients wear a cervical collar postoperatively to minimize strain on the suture line — replacing the more invasive “Grillo stitch,” which historically involved suturing the chin to the chest.

Advertisement

Dr. Tierney views this case as both a success and a cautionary tale.“These injuries are often preventable by keeping the endotracheal tube size appropriate for the patient’s height and making sure that if patients are going to require intubation longer than 10 to 14 days, teams are contacted to establish a tracheostomy early,” he says.

He also underscores the importance of experience and collaboration. “Doing [these major airway reconstructive surgeries] with a team that has done these before is a huge advantage,” he says. “There’s a lot of moving parts and minutiae that make a huge difference.”

The patient’s excellent physical condition and lack of comorbidities were also key factors. “This allowed us to move forward quickly and to target a full recovery,” says Dr. Tierney, while acknowledging that this approach is not the right choice for every patient. “Our decision-making process was extremely patient-focused, which is critical, and should be a priority for every member of the care team.”

This case exemplifies the potential for full recovery—even after a severe airway injury—when patients receive timely, coordinated, and expert care. Thanks to a dual-subspecialist approach and adherence to evidence-based protocols, a patient is now back to living her life — actively and vocally.

“This was a life-changing surgery for her,” concludes Dr. Tierney. “And for us, that’s what makes this work so meaningful.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

New tools and protocols to improve care

Endoscopic balloon dilation during pregnancy helps optimize outcomes

Surgery is typically the only option for the most severe cases, but a minimally invasive procedure is reducing morbidity and recovery time for patients

Cleveland Clinic pulmonologists share a framework for how to implement effective clinical protocols to standardize evaluation and management of complex acute respiratory distress syndrome

A public health tragedy with persistent pathophysiological and therapeutic challenges

Recent breakthroughs have brought attention to a previously overlooked condition

Findings show profound muscle loss variance between men and women

For the first time, risk is shown after accounting for underlying contributions of pulmonary disease