How Cleveland Clinic cardiac surgeons weigh the competing factors

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4808a971-2a03-427d-a93d-783d8847a754/20-HRT-020-endocarditis-650x450-1_jpg)

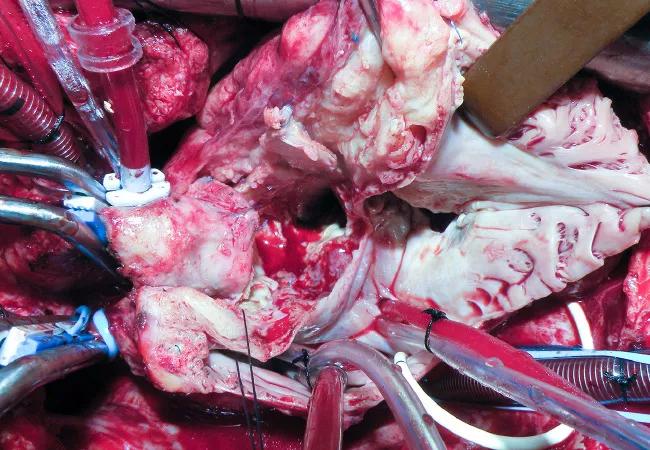

20-HRT-020 endocarditis 650×450

The soaring rate of injection drug use disorder has driven the number of patients with infective endocarditis associated with substance use disorder (SUD-IE) to double since 2007 while cases of IE in individuals who do not inject drugs have remained steady. Nationwide, close to 10% of hospitalized patients with IE have SUD-IE, which corresponds to more than 90,000 hospital admissions annually (J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8[9]:e012969).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Whether cardiac surgeons should perform repeat operations on these patients is a polarizing issue. Surgeons on the “pro” side argue that they have an ethical responsibility to treat patients with an acute problem that is fatal without intervention. Those on the “con” side cite the futility of devoting time, resources and healthcare dollars doing repeat surgeries for patients on a path of self-destruction.

Although Cleveland Clinic has no official policy on repeat valve replacement in patients with SUD-IE, its surgeons have found a workable solution: They generally operate on patients deemed healthy enough to withstand the surgery, so long as the patient is deemed to be treatable for his or her addiction disease.

“Our job is to look at these patients as human beings in their entirety, and that includes evaluating them for comorbid conditions,” says Eric Roselli, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s Chief of Adult Cardiac Surgery, who argued the “pro” side in a debate on this topic at the Society of Thoracic Surgeons annual meeting in January. “If a patient has diabetes that they aren’t controlling, we don’t turn them down for surgery. We make sure they are getting the proper treatment for their diabetes. The same general principle applies for a patient with addiction disease. They need to get optimal therapy for both conditions.”

“Doctors are not judges,” adds Gosta Pettersson, MD, PhD, Vice Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery and a world expert on IE. “We should try to help patients with whatever problems they have and stay away from our personal moral opinions on what is responsible for their troubles.”

Advertisement

Information on the outcomes of surgery in patients with SUD-IE has been limited. In 2015, Dr. Pettersson and colleagues published a study looking at outcomes of all 526 patients with IE surgically treated at Cleveland Clinic from 2007 to 2012 (Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:875-882). Of these, 41 (7.8%) were patients who injected heroin and/or cocaine.

The patients who injected drugs fared as well as nonusers in the first 90 days after surgery. Between days 90 and 180, however, they had a 10-fold higher risk of death or reoperation, with the increase due primarily to reoperation for IE recurrence, not death. Those who survived this critical three- to six-month phase had a subsequent mortality risk comparable to that of nonusers.

As explained in the study report, this high-risk period coincides with the period of greatest risk for return to drug use after detoxification for patients with opiate use disorder. “It is unlikely that the occurrence of IE would serve as an effective deterrent against continued injection drug use,” the authors wrote.

Complex patients like these are discussed by a team of surgeons and other physicians, who assess suitability for surgery on a case-by-case basis. Ultimately, it’s the surgeon who decides whether to operate. “If the surgeon turns down a patient, a second doctor must agree with the decision,” says Dr. Roselli.

Patients who are deemed inoperable may lack the physical strength to withstand another heart operation. Others may have failed multiple attempts to successfully treat their addiction disease, often due to a lack of outside support needed to successfully participate in treatment and rehabilitation. Some even continue to inject drugs while hospitalized.

Advertisement

“Some patients do not demonstrate a capacity to control their own life,” says Dr. Pettersson. “We need a credible indication that they are willing and able to make a commitment to treating their addiction disorder.”

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the standard of care for addiction, yet a lack of treatment programs means only about one-fourth of U.S. patients with SUD-IE receive an addiction consultation, and fewer than 8% receive MAT. Cleveland Clinic has addressed this problem by establishing an in-house protocol.

Patients with SUD-IE are seen by an inpatient psychiatric nurse practitioner who works with the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery; this nurse practitioner screens the patients, begins education on addiction and helps patients start the recovery process while still in the hospital.

Changes in traditional protocols can increase the chance of success. For instance, patients receive intravenous antibiotic therapy in a long-term acute care hospital rather than being discharged with a PICC line.

The post-acute care team hands off the patient directly to addiction treatment under the direction of David Streem, MD, Medical Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Alcohol and Drug Recovery Center and Chairman of the Northeast Ohio Hospital Opioid Consortium, which is working to mitigate the opioid crisis.

“This program enables us to treat the underlying addiction disease as early as possible,” says Dr. Roselli.

While Cleveland Clinic hopes its program increases the chance of reoperation-free survival, outcomes are not yet clear. “We are talking about how best to follow these patients,” says Dr. Pettersson. “We have to believe that when we treat them, we are really helping them.”

Advertisement

Meanwhile, the surgeons are looking at ways to limit injection drug use, reduce the number of patients started on opioids and make drugs less available.

Dr. Roselli is enthusiastic about an app under development that will allow prescribing of precise opioid doses. He is personally working on a solution to the problem of disposing of unwanted opioids.

“The medical and surgical community started the problem by handing out opioids like M&Ms,” he says. “It’s up to our community to find solutions.”

The surgeons’ ethical responsibility to treat a patent with IE sometimes can conflict with their responsibility to the hospital and community. When this happens, their priority is the patient. “Both problems must be addressed,” says Dr. Roselli. “However, until it is futile to treat addiction, it is not futile to treat IE.”

His colleague Lars Svensson, MD, PhD, Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute, concurs.

“We have to treat the patient as a whole — not just the immediate problem of endocarditis, but also any psychological, home and community challenges,” Dr. Svensson says. “We now have these patients followed by our psychiatry team and we have volunteers who have themselves recovered from substance use disorder help patients reintegrate into their families and society. Last year, Cleveland Clinic hosted U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams for a discussion of the broader issue of substance use disorder and the drug overdose epidemic. Fortunately, we are seeing the approximately 70,000 U.S. deaths per year from drug overdose start to decline. Nevertheless, we believe all patients should be given the benefit of the doubt and, if they are otherwise reasonable candidates for surgery, be treated for their endocarditis in the hope they will make a full recovery, not only medically but also as valuable members of our community.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches