Series demonstrates comparable results with an MRI-based decision strategy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/04609552-e26e-4a07-81a8-af69145ff982/21-NEU-2340463-brain-imaging-pediatric-focal-cortical-dysplasia-650x450-1_jpg)

21-NEU-2340463-brain-imaging-pediatric-focal-cortical-dysplasia-650×450

Selecting children with epileptic spasms for surgery based on the location and extent of lesions detected on brain MRI, nearby eloquent regions and preexisting deficits yields seizure-free results comparable to a strategy that includes intracranial monitoring. This MRI-based approach not only reduces risk by avoiding an invasive procedure but allows surgery to be conducted more promptly. So concludes a study — recently published in Epilepsy Research — of a large series of children who underwent surgery for epileptic spasms without invasive monitoring.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“In prior surgical series of children with epileptic spasms, invasive intracranial EEG monitoring has been used in 20% to 65% of patients,” says the study’s corresponding author, Ahsan N.V. Moosa, MD, a Cleveland Clinic pediatric epileptologist. “At Cleveland Clinic, almost all children who have epileptic spasms with an epileptogenic lesion on MRI undergo surgery without invasive intracranial EEG monitoring. This series confirms that this approach is sound.”

Drug-resistant epileptic spasms in children may have a surgically remediable cause, Dr. Moosa notes. Most surgical candidates have an epileptogenic lesion detectable on brain MRI, but often they also have generalized features in semiology and on interictal and ictal EEG, which confuses the picture. The apparent nonlocalized epileptogenic pattern leads some clinicians to seek further data from intracranial EEG monitoring, with either subdural grid and depth electrodes or stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG). But these procedures entail risks of hemorrhage and infection, and their utility in the setting of epileptic spasms is uncertain.

“Observations from such studies have shown that the seizures were determined to arise from and around the lesion detected on MRI,” Dr. Moosa explains. “Therefore, the utility of intracranial EEG monitoring in this setting is unclear.” He adds that children younger than 2 years are generally excluded from SEEG because of potential complications related to the thin skull in these young patients. This may delay epilepsy surgery if SEEG is deemed necessary.

Advertisement

Evidence indicates, however, that delaying treatment in children with epileptic spasms, even by a few weeks, can have detrimental impacts on development. The American Academy of Neurology recommends initiating therapy within a week of onset of newly diagnosed epileptic spasms.

The retrospective study included 70 children with drug-resistant active epileptic spasms (in clusters or sporadic) who underwent surgical resection at Cleveland Clinic between 2000 and 2018. All were under 5 years old (mean age at seizure onset, 6.8 months; median age at surgery, 18.5 months). None underwent intracranial EEG.

All patients had an epileptogenic lesion identified by brain MRI. Seventeen (24%) had bilateral abnormalities that in all cases were strikingly asymmetric and worse on the side of surgery.

Spasms were the predominant seizure type in all patients and were the exclusive seizure type in 32. Sixteen children had additional seizures with focal features on EEG or semiology; other seizure types included generalized tonic-clonic seizures (n = 10), nonmotor seizures with behavioral arrest (n = 12) and myoclonic-atonic seizures (n = 2). Preoperative EEG showed hypsarrhythmia in 56% (39/70).

Etiologies were malformations of cortical development (58%), perinatal infarct/encephalomalacia (39%) and tumor (3%). Surgical procedures were hemispherectomy (44%), lobectomy/lesionectomy (33%) and multilobar resections (23%).

Outcomes were as follows:

Advertisement

Favorable outcomes at six months were associated with:

Increased risk of recurrence was associated with:

Dr. Moosa explains that Cleveland Clinic’s approach to epileptic spasms is to base surgical decisions primarily on the lesion detected on MRI. “The lesions are generally lobar or hemispheric,” he says. “When MRI abnormalities are bilateral, focal features on EEG and seizure semiology have guided surgical decisions.” The type and extent of procedure are influenced by preexisting deficits and anatomic margins of nearby eloquent cortex. Children with symmetrical extensive abnormalities on brain MRI are generally not considered to be surgical candidates, he notes.

He highlights key takeaways from his team’s analysis of this “MRI-based” approach:

Advertisement

“Not requiring invasive monitoring for epileptic spasms offers a faster path to surgery and exposes children to less preoperative risk,” Dr. Moosa observes. “It also opens up the availability of effective treatment in centers without intracranial monitoring capabilities.”

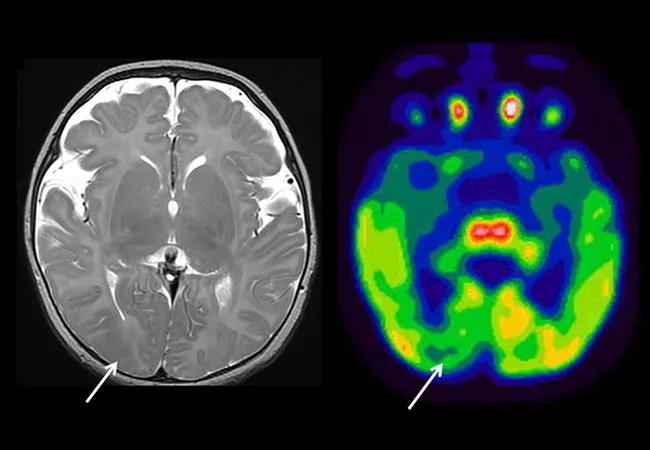

Image at top shows T2-weighted MRI and FDG-PET images from a 3-month-old infant with epileptic spasms and focal seizures. Arrows indicate focal areas of hypointensity and hypometabolism consistent with focal cortical dysplasia.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Insights from one of the first studies of invasive monitoring in the rare form of focal cortical dysplasia

The disease’s neuropathologic heterogeneity holds clues to refining diagnosis and prognosis

A case study in pairing imaging acumen with subspecialty expertise to yield answers and symptom relief

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss