Diagnosis and treatment of MOG antibody-associated disease

A 16-year-old female experienced postpartum headaches after uncomplicated spontaneous delivery of a healthy infant. On postpartum day 3, she developed a fever of 103.1°F and was lethargic, inattentive to conversations and difficult to arouse. The next day, she became unresponsive to her mother and staff and experienced three generalized tonic-clonic seizures. She then was intubated, put on mechanical ventilation, started on magnesium and empiric antibiotics for presumptive bacterial meningitis, and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

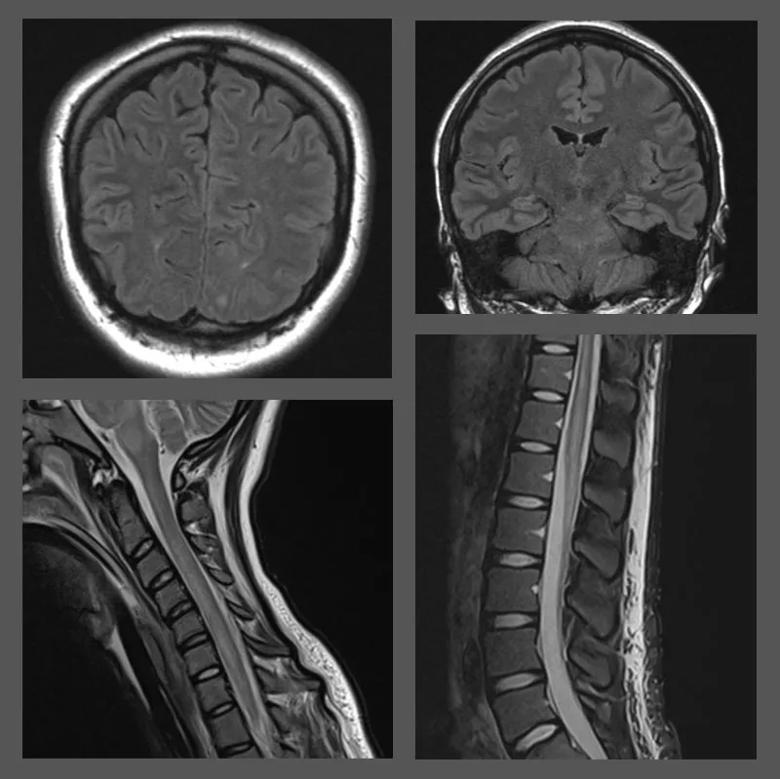

Lumbar puncture demonstrated pleocytosis in the cerebrospinal fluid with 75% neutrophils, which was suggestive of a potential infectious trigger. Despite extensive testing, no organism was identified. MRI showed widespread neuroinflammatory involvement throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (Figure). An initial serum myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) titer on cell-based assay was 1:640 and negative for neuromyelitis optica antibodies.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/64cf90cf-b140-48d6-a892-4471e2680653/23-NEU-3839388-CQD-Inset-800x800-1_jpg)

Figure. Select MRI findings throughout the central nervous system revealing the patient’s pretreatment pathology. The top left image shows a focus of FLAIR signal in the left occipital subcortical white matter. The top right image shows a patchy area of abnormal FLAIR signal in the pons. The bottom left image shows diffuse abnormal increased T2 signal involving the cervical cord. The bottom right image shows confluent hyperintensity in the conus on STIR imaging with patchy hyperintensity and fusiform enlargement.

Based on the clinical history, MRI findings and test results, Cleveland Clinic pediatric neuroimmunologist Aaron Abrams, MD, diagnosed the patient with MOG antibody-associated disease (MOGAD).

The patient’s initial treatment included intravenous pulse methylprednisolone (IVMP) (1,000 mg/d for seven days) and seven cycles of plasmapheresis. The IVMP then was administered for another three days, with a one-month oral taper, and monthly treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was begun.

A repeat MOG titer ordered by Dr. Abrams five days after completion of the last plasmapheresis was 1:100; repeat neuroimaging demonstrated improvement in CNS inflammation. Five months of rehabilitation at an inpatient rehab facility resulted in gradual improvement in the patient’s clinical symptoms. She did suffer a pseudo-relapse with a seizure following strenuous physical activity; she was placed on levetiracetam, which she continues to take, along with the monthly IVIG.

The patient’s most recent MRI and serologic testing (MOG IgG titer 1:100) indicate that she is stable. Ongoing residual issues include right big toe dorsiflexion weakness and pain (for which she continues to receive rehabilitation), as well as rare leg spasms and bowel and bladder problems.

Advertisement

“Overall, this patient has made a remarkable recovery, from being quadriplegic to being able to care for her infant, attending classes and even continuing to play competitive soccer,” says Dr. Abrams. “There is nothing to suggest that she won’t continue to improve with ongoing therapy and enjoy a full and active lifestyle.”

MOGAD is a rare idiopathic, inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the CNS. According to Dr. Abrams, this patient’s case was particularly unusual because her symptoms started a day after delivery of a healthy infant. “It’s possible that the inflammatory cascade associated with childbirth triggered some sort of neuroinflammatory or neuroimmunologic response,” he says.

While the exact incidence of MOGAD is unknown, studies show an equal prevalence in males and females. Typical age at onset is 20 to 30 years, and it can occur both in children and in older individuals. MOG IgG-associated disorders are generally regarded as nonfamilial.

“Over the past year, I’ve seen five to 10 new pediatric cases of MOGAD, which is a lot,” says Dr. Abrams. “I suspect that the increasing incidence may be associated with a combination of increased awareness and testing as well as the COVID-19 pandemic era in which we are living.”

Patients with MOGAD sometimes present with symptoms similar to neuromyelitis spectrum disorder, with recurrent optic neuritis (unilateral or bilateral), transverse myelitis or both. Like the patient here, children with MOGAD often have acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Its symptoms can include decreased consciousness, headache, behavioral changes and seizures. Optic neuritis is a more common presentation in older patients with MOGAD.

Advertisement

“Many conditions, such as meningitis, can present similarly to MOGAD, but their management is different,” Dr. Abrams notes. “Any time clinicians see potential neurological symptoms in a child, such as optic neuritis, they should consider CNS inflammatory disease.”

In patients with MOGAD who present with ADEM, typical MRI findings are diffuse signal changes in the cortical and deep gray matter and subcortical and deep white matter on T2-weighted and FLAIR images. Cell-based assays can be used to test for the presence of IgG targeting. CSF may demonstrate lymphocytic pleocytosis, normal or mildly elevated protein, and rarely oligoclonal bands.

The therapy of choice for initial acute treatment of MOGAD is IV corticosteroids (methylprednisolone IV once daily for three to five consecutive days followed by a prolonged taper). Plasmapheresis or IVIG can be considered as second-line treatment for patients unresponsive to steroids.

Dr. Abrams notes that an area of active research is how MOG antibody titer levels may predict disease course. For patients who relapse, he says, rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil, IVIG and azathioprine have all been considered in this setting.

“Our plan for this patient is to monitor for new lesions or progression with MRI and MOG titers at least annually and to continue the IVIG for two years,” Dr. Abrams observes. “We’ll then reassess and consider whether to decrease the frequency of therapy or switch her to twice-yearly infusions of rituximab, a B-cell-depleting therapy. Management of MOGAD is on a case-by-case basis because we don’t have a lot of longer-term data on the risk of relapse after the first couple of years of treatment. That’s something we’re actively studying.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

GFAP elevation may signal increased risk of progressive regional atrophy, cognitive decline

Model of viral encephalomyelitis shows links with CNS recovery from inflammation and damage

Will enable sharper focus on new diagnostic tools for elusive neurodegenerative disease

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

Despite less overall volume loss than in MS and NMOSD, volumetric changes correlate with functional decline

Findings underscore the value of clinical monitoring in pregnant patients using SSRIs and SNRIs

Novel insights from a postmortem study combining imaging, pathology and clinical perspectives

A principal investigator of the landmark longitudinal study shares interesting observations to date