Cleveland Clinic case series demonstrates feasibility and safety

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a071d234-d600-44d6-b586-f9c5583ecab2/21-HVI-2041380_TAVR_650x450_jpg)

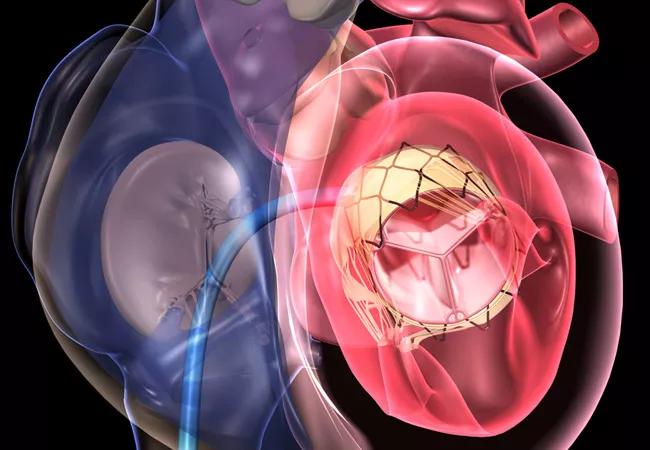

implantation of a TAVR valve

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) can be performed safely in adults with congenital heart disease if done by a multidisciplinary team of specialists at a high-volume center. So concludes a case series of six adults with various forms of congenital heart disease and aortic valve pathology followed for up to 12 months. The series was published in JACC Case Reports (2024;29[4]:102199).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“TAVR can play an important role for adults with congenital heart disease as a bridge to recovery, future surgery or transplantation, or as palliation,” says the report’s senior author, Joanna Ghobrial, MD, MSc, Medical and Interventional Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Adult Congenital Heart Disease Center. “This series provides short-term outcomes data supporting expansion of the role of this minimally invasive option to adults with congenital heart disease, a population that was excluded from TAVR trials.”

The series consisted of six patients treated with TAVR at Cleveland Clinic. Average age was 38 years (range, 25-49). They had varied and complex congenital problems, including tetralogy of Fallot, atrioventricular septal defect, D-transposition of the great arteries, bicuspid aortic valve and Shone complex. Aortic valve pathology was also varied and included aortic stenosis or regurgitation involving prosthetic, native and homograft valves.

Most patients had multiple prior surgeries (median of four sternotomies), and all were at high or prohibitive surgical risk with anatomical and access challenges (see Figure).

All patients underwent TAVR safely without acute complications. The intervention led to significant improvement in hemodynamics and zero to mild aortic regurgitation. Follow-up ranged from three to 12 months.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/36b096dc-842d-4140-ae83-bda95625717f/TAVR-in-congenital-heart-disease-table)

Figure. Unique characteristics of TAVR when performed in patients with adult congenital heart disease. Reprinted from Sharew et al., JACC Case Reports (2024;29[4]:102199), under Creative Commons license BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Having a multidisciplinary team of specialists (Figure) to evaluate and manage these unique patients is essential, according to Dr. Ghobrial. Patients may have tenuous hemodynamics and complex anesthesia requirements. There also are anatomical challenges, she says. For example, some patients may not have a subclavian artery due to prior surgical shunts, which makes the cerebral embolic protection normally employed in TAVR not feasible.

Advertisement

“These patients need the input of adult congenital heart disease experts, cardiothoracic surgeons, interventional cardiologists and relevant subspecialists to determine the best interventional strategy and manage them during the procedure,” she explains. “Referral to a center that has such expertise and handles a high volume of TAVR cases is essential.”

After intervention, prompt and regular follow-up with a congenital heart disease expert is important to monitor valve function, as well as to monitor for valve leaflet thrombosis and infective endocarditis (Figure).

Dr. Ghobrial adds that durability of TAVR for patients with congenital heart disease has yet to be determined. She advocates for extended followup and for multicenter prospective trials to achieve a larger patient cohort with varied conditions.

She also calls for more innovation in TAVR development targeted to this patient population, including new platforms designed to meet their anatomic needs. “These patients tend to have more complex anatomy, making it difficult to navigate TAVR delivery systems,” she explains. “Platforms with a lower profile and more flexibility would be valuable.”

Dr. Ghobrial notes that many cardiologists overlook TAVR as an option in patients with congenital heart disease, as they tend to be considerably younger than the patients who usually undergo this intervention. Generally, young adults are considered for a potentially more durable open surgical strategy, as TAVR valves are expected to last for an average of 10 to 15 years.

Advertisement

“Most of these patients have already had multiple sternotomies, and many will probably have more in the future,” she says. “TAVR may not offer durability to the end of life, but it will likely reduce a patient’s lifetime number of sternotomies, an important goal in itself.”

“The key to long-term success in the care of patients with complex congenital heart disease is to do the right procedure at the right time, being mindful that the long-term goal is to improve quality of life for decades, not just years,” adds case series co-author Kenneth Zahka, MD, who specializes in pediatric cardiology and adult congenital heart disease. “We have shown that TAVR in selected patients can be an essential part of achieving that goal.”

In considering the prospects of TAVR in this setting, Dr. Ghobrial looks to the acceptance of transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement for patients with congenital heart disease and right ventricular outflow tract dysfunction, now regarded as first-line therapy by the American College of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology. She says that although the data are ot yet in for TAVR in adults with congenital heart disease, she hopes that this minimally invasive intervention will one day become standard care.

“TAVR is currently rarely offered to adults with congenital heart disease,” she says. “Knowing that it is safe and feasible in a specialized center, TAVR should be considered more often for the select patients who can greatly benefit from it.”

“TAVR in adult congenital heart disease is an extension of the paradigm that has been successful in older adults with acquired aortic valve disease,” adds case series co-author Tara Karamlou, MD, MSc, Surgical Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Adult Congenital Heart Disease Center. “Our perspective is that in very carefully selected patients, TAVR may be useful as a bridge to another definitive therapy. For example, we have successfully used TAVR as a bridge to surgical AVR following recovery of left ventricular function. TAVR as a bridge to transplantation may be another potential strategy that has borne fruit at other centers.”

Advertisement

“Cleveland Clinic was instrumental in pioneering TAVR many years ago in the pivotal clinical trials, and today we have among the highest TAVR volumes in the world,” notes Grant Reed, MD, MSc, an interventional cardiologist who performs TAVRs in adults. “This case series demonstrates that achieving excellent results from TAVR is possible in adults with congenital heart disease with careful planning and a meticulous, multidisciplinary team approach.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

Experts advise thorough assessment of right ventricle and reinforcement of tricuspid valve

TVT Registry analysis could expand indication to lower surgical risk levels

Reproducible technique uses native recipient tissue, avoiding risks of complex baffles

HALT has unique clinical implications for adults with congenital heart disease

A reliable and reproducible alternative to conventional reimplantation and coronary unroofing

Retrospective study examines outcomes associated with common treatment pathways