A look back on the remarkable surgical career of Toby Cosgrove, MD

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/99cbff21-0456-470d-84c6-8898f3ba0d4d/650x450-Cosgrove-Scrubs_png)

650×450-Cosgrove-Scrubs

As CEO and president of Cleveland Clinic, Toby Cosgrove, MD, sometimes joked that he was “a recovering cardiac surgeon.” As Dr. Cosgrove transitions out of the chief executive role he’s held for the past 13 years, Consult QD looks back on a few highlights from his surgical career at Cleveland Clinic — particularly his achievements as an innovator.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Between 1974 and 2006, Dr. Cosgrove performed more than 22,000 operations, served as Chairman of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery from 1989 to 2004, and earned 31 patents for surgical and medical innovations. He also explored new approaches and techniques to solve pressing surgical problems. “The specialty of cardiothoracic surgery should be one of constant innovation,” he wrote in a 2001 review article. “With most new technology expected to be obsolete in 5-7 years, thoracic surgeons need to draw from their imaginations to find innovative surgical solutions for the future.”

Quite often, he wrote, “discovery favors the prepared mind” — or the combination of knowledge, experience and presence of mind to react to needs and opportunities as they arise. In Dr. Cosgrove’s case, a prepared mind could translate distinctly nonsurgical objects like an embroidery hoop, a hair barrette or a bicycle brake into surgical innovations. Those examples are among the following sampling of a few of Dr. Cosgrove’s ideas and innovations from his stellar surgical career.

In the early days of mitral valve surgery, Dr. Cosgrove was confronted with the relative inflexibility of the retractor then being used for exposing the right and left atria. Noting the adaptability of the retractor he was using for internal thoracic artery dissection (the Favaloro retractor), he combined its best features with features from a mitral valve retractor designed by Denton Cooley, MD. Dr. Cosgrove came up with the infinitely variable and self-retaining device now known as the Cosgrove retractor, which has been in continuous use since the 1980s.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c315e340-66e0-40c1-a286-19cd9f2183b6/Cos-Surg-Retro-CQD-Inset-1_jpg)

The Cosgrove retractor.

When preparing to perform aortic valve replacement in a patient whose ascending aorta (the usual site for cannulation) was calcified and whose femoral arteries (the preferred alternative) were also calcified, Dr. Cosgrove improvised by cannulating the axillary artery, under the arm. He went on to do similar cannulation on 26 other patients with extensive aortic and peripheral disease, demonstrating that the axillary was a safe and effective alternative that also lowered the risk of stroke.

A basic element of mitral valve repair is reinforcement of the annulus — the outer ring that holds the leaflets — to maintain the circumferential structure of the damaged valve. This is challenging because the mitral annulus is saddle-shaped and bends and rolls with each beat of the heart. It also expands toward the posterior. A stiff or unevenly sutured prosthetic annulus wouldn’t stand up to these stresses and would leak or otherwise malfunction. There was clearly a need for a flexible annuloplasty ring, but how could such a ring be evenly and effectively sutured into place?

Dr. Cosgrove found inspiration in the humble embroidery hoop. He noted that the hoop allowed the embroiderer to pull the stitches tight, but when the hoop was removed, the cloth regained its flexibility. He developed a saddle-shaped ring system with closely and evenly spaced holes for sutures, allowing the surgeon to evenly fold and suture the cloth used to reinforce the annulus. The result was mitral valve repair that was leak-free and flexible enough to roll with the motion of the heart.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/717182d5-1acc-4e69-8ffe-3d99617b727b/Cos-Surg-Retro-CQD-Inset-2_jpg)

The flexible annuloplasty ring.

Large-handled clamps that shut the aorta during cardiac surgery can also block the surgeon’s view. Dr. Cosgrove saw an opportunity to develop a clamp whose handle could be activated from a distance, away from the surgeon’s tiny working space. Inspired by the concept behind bicycle hand brakes, he designed a flexible clamp whose handle could lay outside the surgeon’s line of sight. The resulting Cosgrove Flex Clamp continues to be used and refined.

During cardiac surgery, venous blood is drained through a cannula out of the heart and into the extracorporeal oxygenator, or heart-lung machine. Ordinarily, the cannula needs to be large because blood is moved through it by a gravity-driven siphon effect, which also requires the heart-lung machine to be close to the ground. While a large cannula is acceptable in a conventional surgery, it takes up too much room and blocks the surgeon’s view in a minimally invasive operation. Dr. Cosgrove saw that a number of problems could be solved by replacing the siphon with a vacuum device. He designed and patented this innovation. The results included smaller cannulae and better visualization, less need for blood transfusion, less need for blood prime (a liquid that mixes with blood during extracorporeal oxygenation) and other benefits that improved surgical efficiency and patient outcomes.

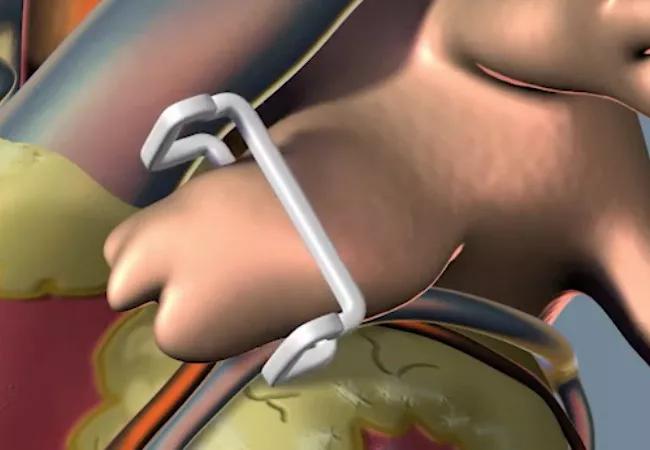

One of Dr. Cosgrove’s most recent innovations reduces the risk of stroke caused by blood clots originating in the sac-like heart structure called the left atrial appendage (LAA). Blood tends to pool and clot in the LAA. The clots escape through the mouth of the LAA and can travel to the brain, causing neurological damage. Working with A. Marc Gillinov, MD, now Chair of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Cosgrove developed a clip that can be surgically placed over the mouth of the LAA, blocking the exit to prevent thrombi from making their way into the bloodstream. Dr. Cosgrove says he arrived at the clip idea after seeing his daughters’ hair barrettes.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4a7e08f6-bfda-4f74-8350-f57538fc55b0/Cos-Surg-Retro-CQD-Inset-3_jpg)

Illustration of the Gillinov-Cosgrove™ LAA Clip.

Some of Dr. Cosgrove’s ideas were ahead of their time and were later brought to maturity by others. Most of his ideas were realized only after long periods of analyzing a particular problem and the lengthy, sometimes discouraging process of trial and error. “I can attest,” he wrote, “that new enterprise receives little support and much criticism.” On the process of innovation itself, Dr. Cosgrove once quoted Louis Pasteur, saying, “My strength lies solely in my tenacity.”

“Dr. Cosgrove is always pushing himself and others to go beyond their comfort zone,” says cardiothoracic surgeon Tom Mihaljevic, MD, who will become CEO and president of Cleveland Clinic on Jan. 1, 2018. “His personality translated into his style of leadership, and has had immeasurable impact on cardiac surgery and Cleveland Clinic.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center