And two case vignettes where some of them come into play

Dealing with “nightmare scenarios” in congenital heart surgery — cases that start out tough or unexpectedly turn dire — requires a systematic approach, including thorough preparation for potential complications, excellent communication with the entire healthcare team and a willingness to completely redo a prior surgery if necessary. These are among the strategies described by Hani Najm, MD, MSc, in a presentation at the recent virtual 2021 annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Every surgeon has ‘nightmare cases,’” says Dr. Najm, Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “Preparing for expected problems is a given, but having strategies to cope with the unexpected is also needed.”

Dr. Najm discussed his key tactics, outlined below.

When presented with a case that he foresees may become a quagmire, Dr. Najm mentally runs through the following algorithm to help him decide how to best proceed:

Age is another important consideration: younger patients have potentially longer life expectancy and are likely to have acquired less damage to other systems, making recovery smoother.

Finally, prognosis with or without surgery must be assessed. “What will quality of life likely look like in five years? 20 years?” Dr. Najm asks himself. “These questions strongly influence my decision on how much risk to take.”

There are usually many ways to tackle technical difficulties in the operating room, and being thoroughly prepared for all of them is critical in case something goes wrong with the chosen option. There is no substitute for experience, Dr. Najm emphasizes, but he also consults the literature and his colleagues. “You can’t execute what you haven’t thought about beforehand,” he adds.

Advertisement

Dr. Najm stresses that excellent pre- and perioperative communication with the entire surgical team —anesthesiologist, nurses, perfusionists and others — is critical in complex cases. “Everyone should be on board with what we’re doing and know what to expect and watch for,” he says.

If you don’t think the repair will be long-lasting, fix it while you have your best chance.

Thoroughly explore the cause of any unexpected postoperative complication — by repeating tests and imaging studies — and go back to surgery if necessary. Be prepared to break down and reconstruct a repair to either find an answer or correct a problem.

In his STS presentation, Dr. Najm shared several illustrative cases, including the two examples below.

A 21-year-old woman presented after an episode of syncope and long-standing chest pain. She had congenital complex left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and in infancy had undergone subclavian flap aortoplasty and subaortic stenosis resection. Two years before this presentation, she had vague complaints of chest pain. Evaluation at that time was remarkable only for a stable small right coronary artery aneurysm. She was given a diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome and underwent first rib resection and left carotid subclavian artery bypass. Her symptoms persisted.

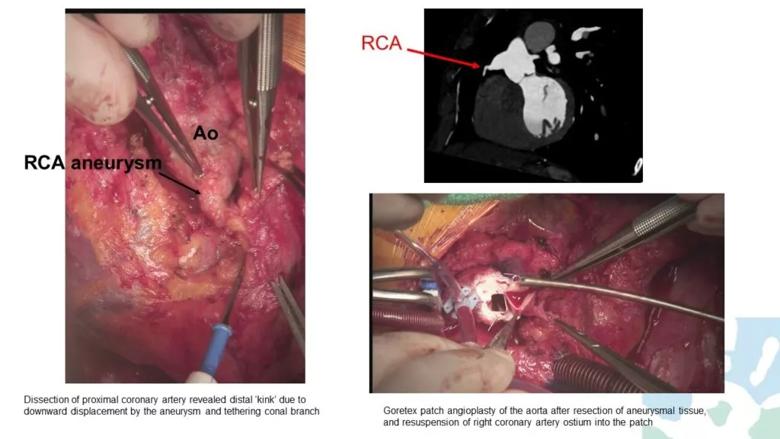

Repeat evaluation revealed a right coronary artery aneurysm, now a bit larger. Upon surgical exploration, it was discovered that the coronary artery was “kinked” due to downward displacement of the aneurysm, which was tethered to the conal branch. A Gore-Tex patch angioplasty of the aorta was performed after resection of the aneurysmal tissue, with reimplantation of the right coronary artery ostium into a higher position in the patch (Figure 1). Her symptoms resolved.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f84b21ea-c5da-4074-8eb4-c8b09235c0b9/21-HVI-2073953-congenital-heart-surgery-inset-1-1024x576_jpg)

Figure 1. Intraoperative photographs and related imaging findings from case patient 1.

A 33-year-old man presented with fevers to 39°C, tachycardia, leukocytosis and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Prior cardiac interventions included the following:

He underwent evaluation with CT angiography and both transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, which indicated the following:

He was diagnosed with endocarditis of the Melody valve, with unclear primary source and extent. Cardiac catheterization with intracardiac echocardiography revealed peak right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) gradient of 3.5 m/s.

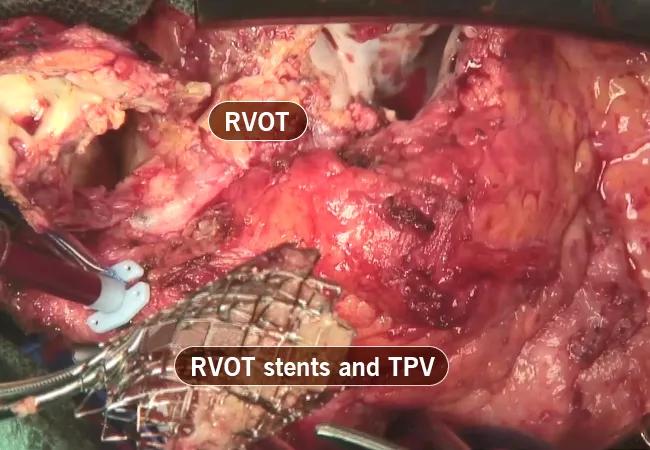

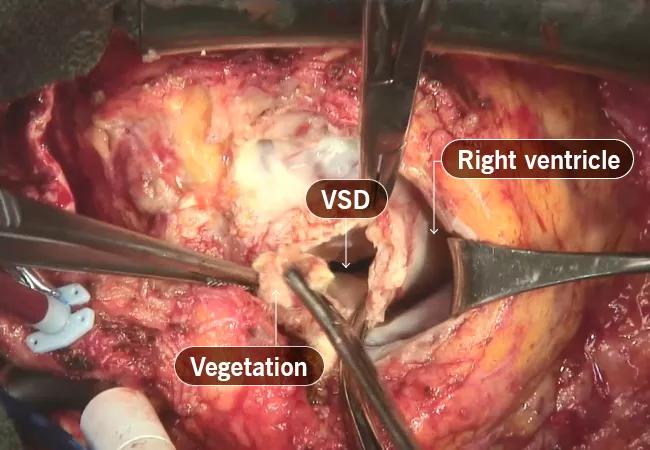

During surgery, extensive infection was found. The infected Melody valve was contained within multiple layers of RVOT stents (Figure 2). The RVOT conduit was removed and infected tissues were debrided. While the heart was beating and the conduit was being removed, a gush of blood rushed out of the left ventricle, indicating involvement of a previously placed ventricular patch (Figure 3). This was not anticipated, so quick measures were taken to stop the heart and remove the patch and the aortic valve, followed by replacement of the valve, ventricular patch and conduit.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/dec0721c-985f-4377-ae4c-dc8b4d78e81f/21-HVI-2073953-congenital-heart-surgery-inset-2_jpg)

Figure 2. Intraoperative photograph of the explanted Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve (TPV), which was contained within multiple layers of RVOT stents.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/17620e01-eb85-4dc1-b92e-5c52835f9007/21-HVI-2073953-congenital-heart-surgery-inset-3_jpg)

Figure 3. Intraoperative photograph of the surgeon’s view of the RVOT after removal of the RVOT conduit and debridement of the infected tissues. There was a large defect in the interventricular septum from infection of the patient’s prior ventricular septal defect (VSD) patch.

Dr. Najm credits the successful resolution of these cases to an aggressive approach: “When a case turns into a nightmare, the surgeon has to become aggressive, both in searching for the cause of the complication and in fixing it.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center