Refinements introduced to Cleveland Clinic-developed approach to a rare defect

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1866cb5b-495e-48a1-81a0-fa9a9b25949e/HVI-1572623_04-29-19_018_MLC-jpg)

3D heart

In congenital heart surgery, paradigm shifts are few and far between. The rarity of most congenital defects has kept opportunities for such shifts relatively limited. As a result, milestone developments such as the atrial switch and arterial switch procedures are now well established, having been practiced for multiple decades.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Yet a Cleveland Clinic team led by Hani Najm, MD, Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery, suspects a new paradigm shift may be at hand with their development of a novel approach to biventricular conversion in “unseptatable” hearts that they have termed the ventricular switch.

The team reported positive results of the approach in their first five patients at the 2020 American Association for Thoracic Surgery scientific session early last year, and they recently published those results in full in Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2021;33:172-180). The team has since used the approach in several additional patients, incorporating several new refinements they believe will further enhance its impact.

The term unseptatable has been applied to the hearts of patients with complex systemic and pulmonary venous anatomy commonly characterized by atrioventricular canal defects and conotruncal anomalies. These patients have traditionally been treated with univentricular palliation, which leaves them subject to poor long-term survival and few rescue options if the univentricular circulation begins to fail.

The ventricular switch involves biventricular conversion, or septation, in these so-called unseptatable hearts. “We use both ventricles, with the morphologic left ventricle serving as the subpulmonary ventricle to basically recapitulate the physiology of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries,” explains Dr. Najm, who led development of the novel approach. “We have formalized a combination of procedures that lead to a systemic right ventricle, as opposed to a single ventricle, in patients whose hearts have multiple abnormal connections.”

Advertisement

The team’s recently published initial series of ventricular switch cases involved five consecutive patients with challenging anatomic configurations, severe cyanosis and extreme functional limitations. The patients, who ranged in age from 11 months to 46 years, all required complex atrial septation informed by comprehensive planning using 3D-printed heart models.

As detailed in a prior Consult QD post, ventricular switch was successful in all five cases:

Since the report of these five cases, the Cleveland Clinic team has applied the ventricular switch to four additional patients — with some refinements, as enumerated below.

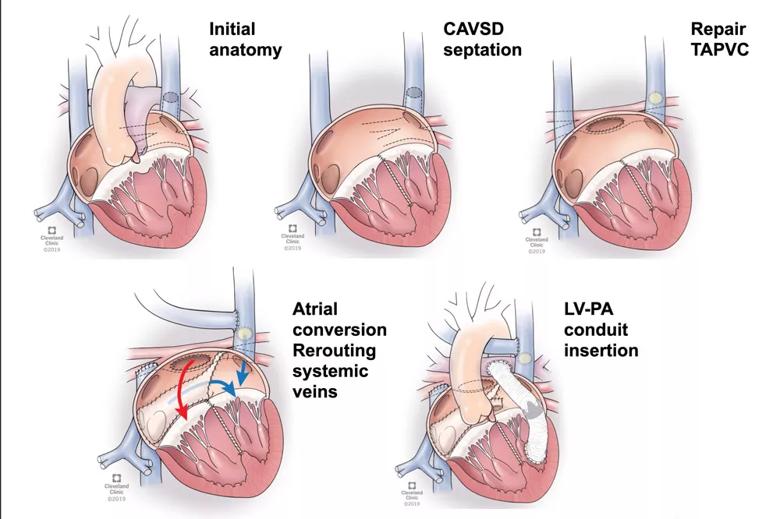

1) Staging. Dr. Najm notes that the ventricular switch is actually a series of five sequential steps (Figure) outlined in the team’s published report of their initial five cases:

“This is not a single procedure but rather multiple procedures that culminate in the use of the right ventricle for systemic circulation,” he explains. “We believe it is better for these various components of the ventricular switch to be staged into two or three operations rather than all done in a single operation.” He adds that the specifics of the staged breakdown of procedures should be left to the surgeon and informed by the child’s development and overall management.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6e488646-148b-4614-818a-d0b7785d2159/21-HVI-2081508-ventricular-switch-Inset_jpg)

Figure. Illustrations showing the key sequential components of the ventricular switch. Steps 3 and 4 are combined in the fourth illustration.

2) Earlier intervention. “As we gain experience, we believe the ventricular switch should be done early in life — ideally before age 2 years,” Dr. Najm observes. “The idea is to set these patients up with an alternative to the univentricular heart at the beginning of their lives and to undertake the ventricular switch as part of the planning for their long-term care. The heart that is prepared early in life is apt to fare better than the heart prepared later.”

He notes, however, that this is currently only a clinical impression that has not been evaluated in clinical trials. And he emphasizes that it does not mean the ventricular switch should not be considered later, as four of the five initial patients were well beyond age 2 years and have had positive results thus far.

3) Systemic atrioventricular valve ring. When the right ventricle becomes the systemic ventricle as a result of the ventricular switch, the atrioventricular valve, which is usually on the right side, may dilate and leak as a result of being pressurized. In response, Dr. Najm’s team has begun routinely adding a left atrioventricular valve ring as a prophylactic measure to preserve the competency of the valve.

4) Branch pulmonary artery band in selected cases. In patients requiring one-and-a-half ventricle repair — as was the case in one of the five initial patients — a pulsatile bidirectional Glenn procedure is required. The team is now adding a branch pulmonary artery band before performing the Glenn to reduce the pulsatility of the Glenn and thereby reduce the risk of postoperative pleural effusion.

Advertisement

“We believe these refinements will further improve the ultimate outcomes of patients undergoing the ventricular switch,” Dr. Najm says.

A key appeal of this new approach, he adds, is that it can be readily adopted without significant training, as the individual component procedures (outlined in the bulleted list above) are familiar to virtually all congenital heart surgeons. What’s novel is the deliberate, proactive planning to use the procedures in coordinated combination to create a systemic right ventricle.

Key to that planning is multimodality imaging, which plays an important role in optimizing patient selection, notes Tara Karamlou, MD, MSc, a Cleveland Clinic pediatric and congenital heart surgeon who works with Dr. Najm. “We have used both CT and MRI with 3D model building to facilitate operative planning,” she says. “These models are extremely important since surgical procedures usually consist of multiple components that must be coordinated. Part of our iterative approach has also been informed by the retrospective review of models in situations where modifications have been suggested.”

The significance and innovation of this ventricular switch approach is noted by two commentaries that accompanied the publication of Cleveland Clinic’s initial case series in JTCVS Techniques. Sitaram Emani, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital called the report “a very important contribution to the field,” and David Barron, MD, of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto wrote of the series: “Even when there is no immediately apparent surgical option, standing back and thinking outside the box can sometimes provide unexpected and innovative solutions.”

Advertisement

Both commentaries note eagerness for long-term data on patients undergoing the ventricular switch, a sentiment shared by Dr. Najm. He says his team will continue following the initial five cases and subsequent patients, with a particular focus on the function of the right ventricle over time.

Another thing he’ll be watching is what potential failure of the ventricular switch’s systemic circulation may look like. “Our new approach offers patients a better quality of life through a biventricular circulation, and we’re hopeful it will offer greater survival than with univentricular circulation,” Dr. Najm says. “But we also expect it will set patients up for a better failure model if and when failure develops.”

He explains that when failure sets in with a univentricular heart after a Fontan procedure, it manifests as multiorgan failure, with high risk of liver cirrhosis, kidney failure, protein-losing enteropathy and more. “In contrast,” he says, “patients with biventricular circulation will fail with a heart failure pathophysiology, without all the multisystem components. That means they can be considered for heart transplantation or mechanical circulatory support or other heart-specific options. These patients are set up for a more manageable failure model if needed — one with alternatives.”

Advertisement

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon