11-year-old with two ventricles and history of D-TGA, VSD and coarctation of the aorta

Plastic bronchitis, an unusual complication usually associated with Fontan palliation of single-ventricle physiology, can also present in a patient with two ventricles in the setting of right-sided heart failure. Such was the case in a recent pediatric patient at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“This case illustrates how plastic bronchitis can be a manifestation of high right-sided pressure in a patient with two ventricles — and the fact that it can be treated by correcting important anatomic lesions,” says Cleveland Clinic pediatric and congenital heart surgeon Tara Karamlou, MD, one of the key surgeons involved with the case.

An 11-year-old boy was admitted to the intensive care unit with respiratory distress and expectoration of bronchial casts every few days. He had a history of dextro-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) with ventricular septal defect (VSD) and coarctation of the aorta, for which he underwent neonatal arch repair, an arterial switch operation and VSD repair. The operations were complicated by a long period of renal failure, from which he recovered.

Subsequently, he underwent five more sternotomies to address the following issues:

At age 9 years, he required the following additional surgeries:

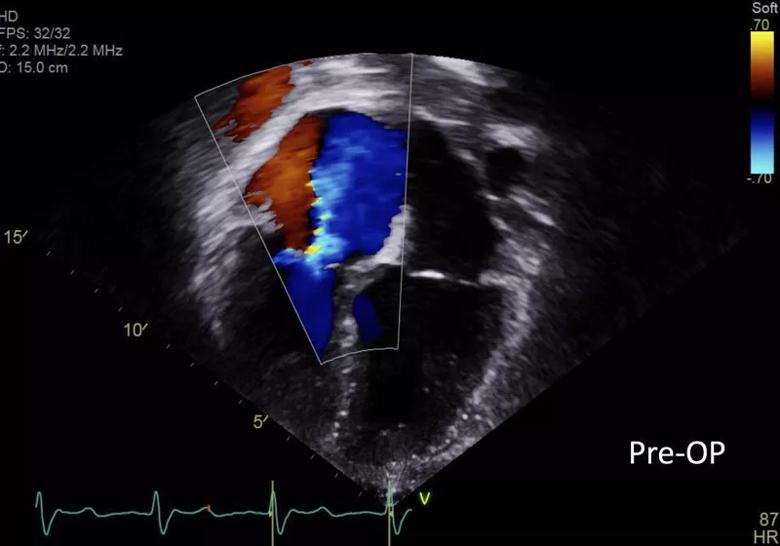

Over the prior two years, he developed severe tricuspid regurgitation (Figure 1), elevated right ventricular pressures and severe homograft valve regurgitation with mild stenosis of the branch pulmonary arteries. Despite having no related symptoms, his liver had been 4 cm below the right costal margin. Until this presentation, he had been relatively stable on diuretic therapy.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/12e8f444-4ddf-4294-b9fc-5968e24573cc/20-HRT-069-Karamlou-Zahka-inset1-800x560-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Echo at presentation showing severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Physical examination at presentation was particularly remarkable for an even more enlarged liver (5.5 cm below the right costal margin) and pronounced jugular venous distention (Figure 2).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b6204a14-d0bf-42a1-9714-3f268eba2e4e/20-HRT-069-Karamlou-Zahka-inset2-800x772-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Pronounced jugular venous distention at presentation.

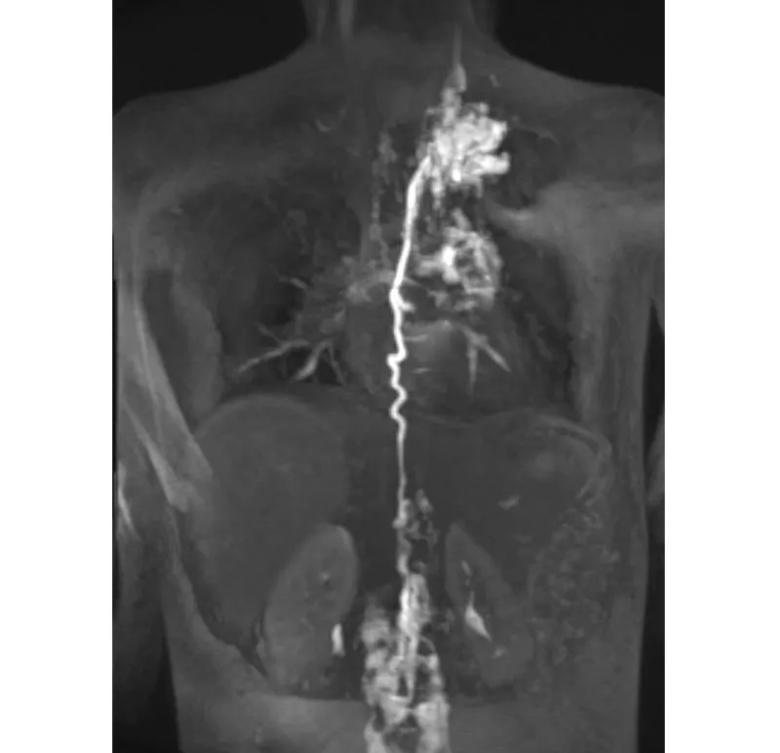

Cardiac catheterization confirmed elevated right-sided diastolic pressures. MR lymphangiogram revealed collateralization of obstructed lymphatic vessels (Figure 3).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a9671d95-6798-4a6a-a28f-21d97277b79a/20-HRT-069-Karamlou-Zahka-inset3-800x772-1_jpg)

Figure 3. MR lymphangiogram at presentation showing collateralization of obstructed lymphatic vessels.

“Because of the role that abnormal pulmonary lymphatic flow plays in plastic bronchitis, our team first considered lymphatic mapping and occlusion of draining lymphatic tributaries as an avenue to treatment,” says Cleveland Clinic pediatric cardiologist Kenneth Zahka, MD, the patient’s primary cardiologist, who explains that this strategy can be successful for plastic bronchitis with recalcitrant chylous effusion. “However, in the setting of abnormal hemodynamics and his striking physical exam findings indicating high right-sided heart pressures, we decided to try to correct his blood flow first.”

The team adopted a staged approach in which the pulmonary artery and pulmonary valve issues were first corrected, as these could be approached percutaneously. The patient underwent left pulmonary artery stenting and transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Despite that, he progressed to daily cast formation and respiratory failure.

Advertisement

The decision-making at this point was to proceed to a more invasive strategy to address the remaining right-sided lesions. He underwent surgical repair of the tricuspid valve, with improvement of his right-sided pressures.

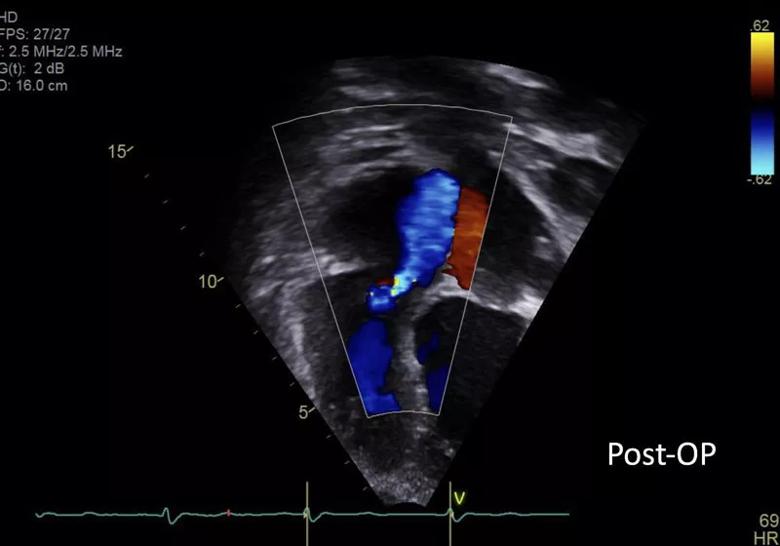

Over the next two months, the patient showed dramatic clinical improvement, with rare cast expectoration and no subsequent hospitalizations. His liver edge receded to 2 cm, his jugular venous distention resolved and postoperative echo showed a reduction from severe to mild tricuspid regurgitation (Figure 4). He reported feeling “back to normal.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4bf32e88-e712-41a1-94a1-c52c6fb0b59d/20-HRT-069-Karamlou-Zahka-inset4-800x560-1_jpg)

Figure 4. Postoperative echo showing mild tricuspid regurgitation.

Drs. Zahka and Karamlou note that this unusual case underscores the following points:

Advertisement

“Plastic bronchitis remains a challenge to the congenital heart disease team,” says Hani Najm, MD, Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “It likely results from lymphatic system hypertension, an entity that is not well understood.” He notes that an obstruction to the drainage of the thoracic duct or elevation of the venous pressure may cause lymphatic hypertension.

“In this patient, the presence of a severe leak in his tricuspid valve could have aggravated the hypertension,” he continues, “and decreasing the right atrial pressure made absolute sense to improve this. A tricuspid valve repair was undertaken to lower the pressure of the downstream drainage.

“We still have a lot to understand about the pathophysiology of the lymphatic system,” Dr. Najm concludes, adding that he’s optimistic that newer procedures will emerge to alleviate this problem.

Advertisement

Advertisement

LLM-driven system uses both structured and unstructured data, provides auditable justifications

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics