Necessity breeds innovation when patient doesn’t qualify for standard treatment or trials

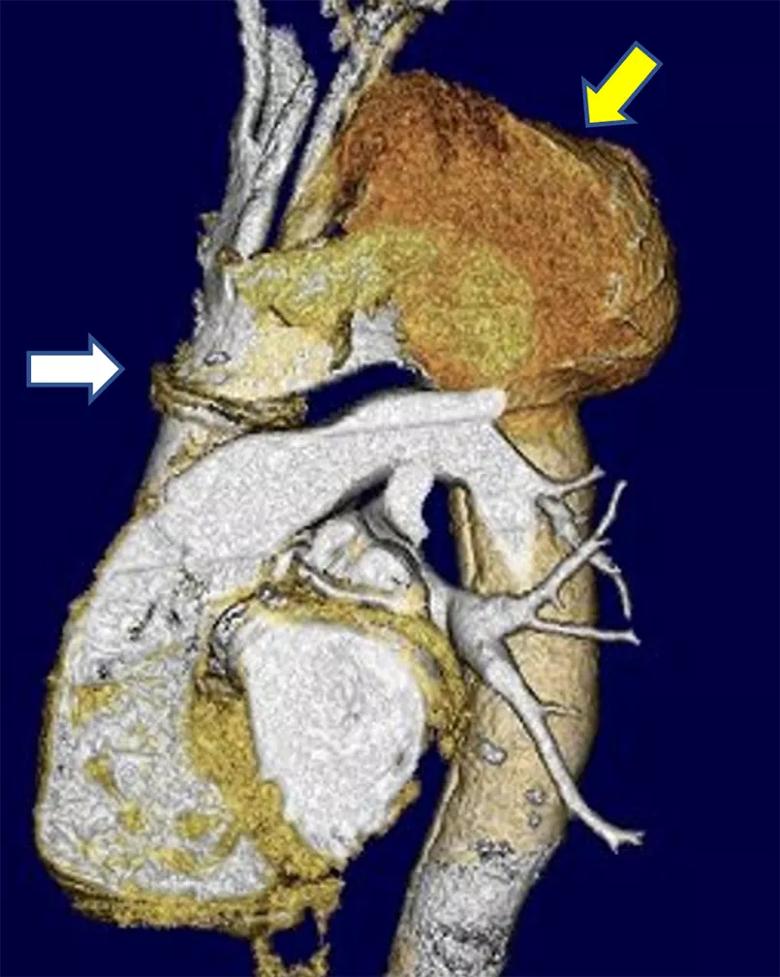

A 65-year-old man presented to Cleveland Clinic’s Aorta Center with an extremely large aneurysm bulging on top of the aortic arch (Figure 1). Several years prior, he had an acute aortic dissection repair at another institution, involving ascending aortic root repair and aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve. Leakage into the aortic arch had slowly occurred since then.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1fa7e046-587d-463d-8c03-c2bacd4076fe/22-HVI-2987079-CQD-Inset-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Preoperative volume-rendered CT scan demonstrating a seam at the distal anastomosis of the prior repair (white arrow) and a massive arch aneurysm of the false lumen in the aortic arch (yellow arrow).

He also had advanced-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), requiring continuous oxygen therapy at a stable rate for a couple of years. Otherwise, he was quite functional and able to participate in family and other activities.

Cleveland Clinic’s Aorta Center is the largest in the U.S., with over 1,400 open and endovascular operations performed in 2021, including more than 1,000 involving the thoracic aorta.

Aorta Center Surgical Director Eric Roselli, MD, is principal investigator of the B-SAFER (Branched Stented Anastomosis Frozen Elephant Trunk Repair) physician-sponsored investigational device exemption (PS-IDE) clinical study focused on the outcomes of that innovative procedure, which he developed. Further work on an innovative device called PHASTER (Proximal Hybrid Aortic Stent Graft for Thoracic Extended Repair) to facilitate this operation is currently undergoing research and development with an industry partner. The Aorta Center team has consistently performed more than 120 total arch replacements using these novel hybrid techniques for the last several years. This patient was not a candidate for these techniques, which require an open surgical approach as part of the repair.

Management of aortic arch disease is rapidly improving, as a variety of single- and double-branched devices are under investigation that can be implanted with less-invasive hybrid surgical/endovascular procedures. They provide the possibility of life-saving interventions to patients who are not candidates for traditional or hybrid open surgery, such as this patient with severe COPD. Cleveland Clinic is an active participant in ongoing trials of all these devices, but this patient did not qualify for these trials either, due to his mechanical aortic valve and other anatomical limitations.

Advertisement

“For patients who could potentially benefit from aortic arch repair but do not qualify for clinical trials of new devices or techniques, options are severely limited,” says Dr. Roselli, Chief of Adult Cardiac Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “But the large volume of cases we treat gave us confidence that we could come up with a creative solution to help this man who had no traditional path to intervention.”

In collaboration with Aorta Center colleagues in vascular surgery and cardiothoracic surgery, Dr. Roselli embarked on a two-stage intervention using modified, but readily available, tools.

Stage 1: Preparation for a single-branch device. An incision was made from the base of the neck to the top of the manubrium to expose the upper part of the thoracic inlet and all branch vessels where they originate from the aortic arch. The left subclavian artery was transposed to the left common carotid artery, and an interposition bypass was created between the left common carotid and innominate arteries. The origins of the innominate and subclavian arteries were then ligated (Figure 2). The brain was now supplied by inflow from the left common carotid artery. The upper manubrium was reapproximated with a titanium plate.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cbf1c7f3-5eec-46d4-b459-194db2d344a6/22-HVI-2987079-CQD-inset-2a_jpg)

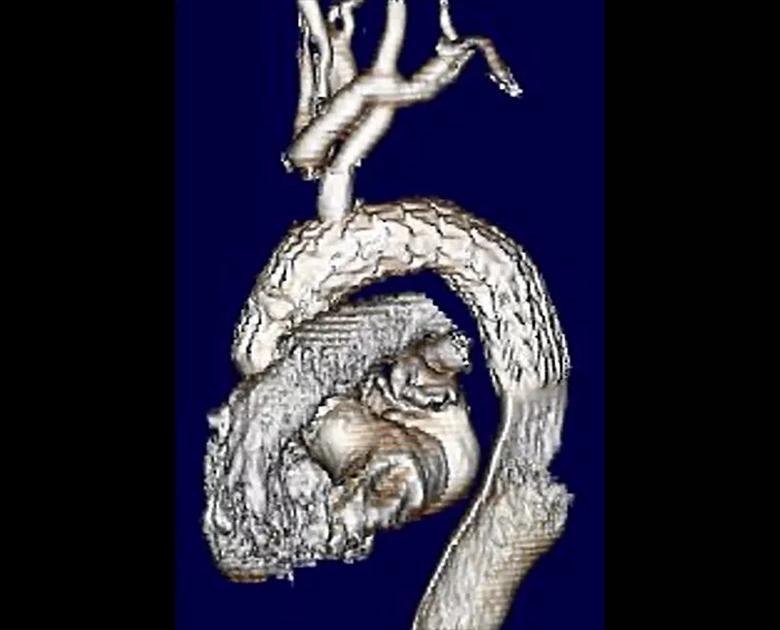

Figure 2. Volume-rendered 3D CT demonstrating the reconstructed supra-aortic branch vessels now supplied by inflow from the 10-mm left common carotid artery to the re-routed innominate and left subclavian arteries following the first stage of the aortic arch reconstruction.

Advertisement

The patient tolerated this procedure well. He was extubated in the operating room and had a good recovery, with no increase in oxygen requirements after a three-day hospital stay. He was then discharged home, as the team hoped to enroll him in one of the single-branch stent graft trials.

Stage 2: Single-branch device constructed inside patient. After several unsuccessful attempts to gain the patient access to one of the branched stent graft trials, the decision was made to proceed with completion endovascular aortic repair with a modification of a commercially available device a few months after the initial debranching procedure.

For this stage, the patient was put on partial cardiopulmonary bypass draining blood from the right atrium via the femoral vein and returning arterial blood from the oxygenator through an inflow cannula to the right axillary artery. Brain perfusion was carefully monitored throughout the procedure using near-infrared spectroscopy. A commercially available stent graft was then delivered from percutaneous access in the femoral artery to the ascending aorta graft, bridging across the arch and into the upper part of the descending aorta (see video below). Once deployed, the stent graft covered the entire arch, including the new “pitchfork” branch vessel reconstruction, and sealed off the aneurysm. Brain flow was adequately supplied via the axillary artery cannulation and the cardiopulmonary bypass pump.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_cw6i5hy7/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Next, a long spinal needle was delivered via neck access using X-ray guidance through the left common carotid artery, and the stent graft was punctured from above. A wire was delivered through the needle into the arch and snared from access via the femoral artery. This through-and-through wire access provided a wire pathway commonly called a “body floss” technique. The hole in the graft was then enlarged serially with successively larger balloons, and a covered 10-mm diameter stent was delivered into the left common carotid artery. This was also serially dilated across the orifice in the graft to reestablish blood flow to the brain. After the endovascular arch reconstruction was accomplished (Figure 3), the patient was easily weaned from the partial cardiopulmonary bypass with no change in cerebral oximetry measures.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/faa2bfad-717c-4060-9601-4a0be8e93e0d/22-HVI-2987079-CQD-Inset-3a_jpg)

Figure 3. Volume-rendered 3D reconstruction of the completed hybrid aortic repair demonstrating a patent branch into the left common carotid artery then supplying the debranched head vessels above. Note that the aneurysm is no longer being opacified with contrast.

The patient was again extubated in the operating room and discharged home after a four-day hospital stay without respiratory or other complications. He was noted to be doing well at one-year follow-up. The aneurysm has shrunken on CT with no evidence of endoleak and a widely patent arch branch. Although the patient is still limited by his COPD, his risk of an aortic rupture has been alleviated.

Dr. Roselli urges colleagues to not give up on patients who need aortic repair and are not surgical candidates without first exploring other possibilities.

“Ideally we can use an investigational device and avoid the need for cardiopulmonary bypass,” he says. “But even if a patient is not a candidate for one, we might still have some options.” Since the time of this procedure, one of the single-branch endograft devices has been approved by the FDA for commercial use in more distal arch aneurysms.

“Patients with advanced arch aneurysms who are not fit for traditional aortic surgery and do not meet criteria for clinical trials are often left in a clinical limbo,” observes Francis Caputo, MD, Vascular Surgery Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Aorta Center. “We have found that by drawing on our vast experience in a multidisciplinary approach, taking what we have learned by working together, we can develop patient-tailored solutions to complicated problems.”

Advertisement

Dr. Roselli adds that although just about any aneurysm can be fixed technically, it might not always be advisable to do so. In addition to aorta and valve details, noncardiac comorbidities must be considered. Moreover, the surgical team’s experience with new techniques and access to newer technology is critical to optimize patient outcomes.

“It’s important to keep in mind that we treat the whole patient, not just the aorta we see on a CT scan,” he says. “Patients should strive to live as long as possible but also need to be sure that we help them live well by keeping the burden of intervention to a minimum.”

Advertisement

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches