Excessive dynamic airway collapse presenting as dyspnea and exercise intolerance in a 67-year-old

By John Barron, MD; Siva Raja, MD, PhD; Thomas Gildea, MD; and Sudish Murthy, MD, PhD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 67-year-old male presented to thoracic surgery clinic with complaints of worsening dyspnea on exertion and exercise intolerance that had been ongoing for four to five years. His symptoms initially were attributed to asthma but were later thought to be potential sequelae of gastroesophageal reflux resulting in laryngeal tracheal reflux and possible tracheobronchomalacia. He underwent surgical fundoplication without improvement in his respiratory symptoms.

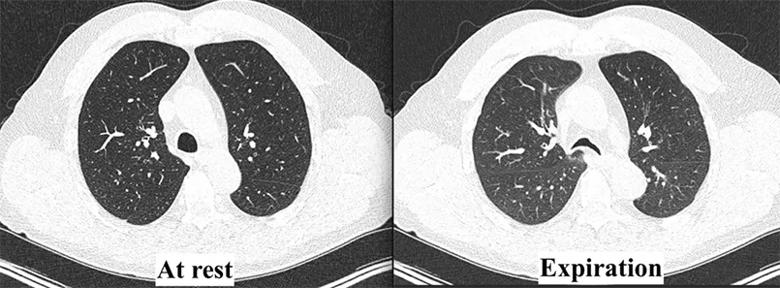

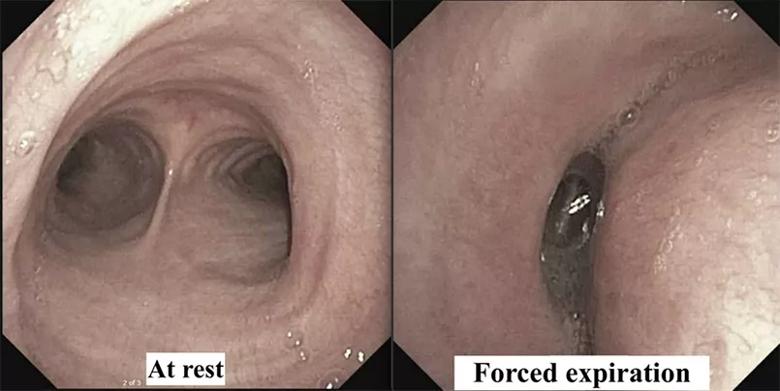

At Cleveland Clinic, the multidisciplinary tracheobronchomalacia team performed a thorough evaluation. The patient underwent dynamic CT imaging of the airway, which demonstrated a greater than 50% decrease in diameter of both the lower trachea and the central bronchi upon expiration, morphologically consistent with excessive dynamic airway collapse (Figure 1). This was followed by dynamic bronchoscopy, which noted a hypermobile posterior membranous airway, with greater than 90% airway occlusion upon forced expiration (Figure 2). This confirmed severe excessive dynamic airway collapse. Complete evaluation noted that he had no evidence of other structural airway disease, connective tissue disease or other entities; hence, his airway collapse was thought to be a sequela of chronic reflux and/or chronic inhaled corticosteroid use.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/51ff6758-b166-4a9f-899b-b7ed759684da/23-HVI-3914171-CQD-Inset1_jpg)

Figure 1. Dynamic CT demonstrating a > 50% decrease in tracheal diameter upon expiration, consistent with excessive dynamic airway collapse.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/66b3c723-d0f2-490d-bd88-996decfdf2d9/23-HVI-3914171-CQD-Inset2_jpg)

Figure 2. Flexible bronchoscopy demonstrating a hypermobile posterior membranous airway with > 90% airway occlusion upon forced expiration, confirming the diagnosis of severe excessive dynamic airway collapse.

Advertisement

Preoperative pulmonary function testing demonstrated a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 53% predicted, with a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 83% predicted and normal exercise stress testing. He underwent a stent trial with temporary placement of a 3D custom silicone Y stent, a technology developed by Cleveland Clinic pulmonologist Thomas Gildea, MD. This resulted in symptomatic improvement in his dyspnea.

Importantly, identification of appropriate surgical candidates is a multidisciplinary exercise. Given the patient’s symptoms, imaging findings and palliation of dyspnea with the stent trial — together with his pulmonary function testing and normal exercise stress test — he was deemed to be appropriate for surgical stabilization of the membranous airway, or tracheobronchoplasty.

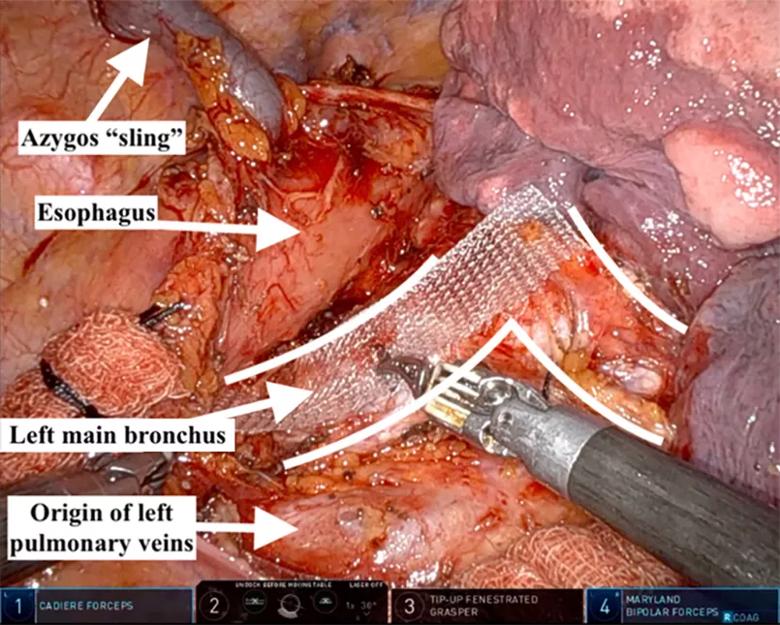

The patient decided to proceed with robotically assisted tracheobronchoplasty, performed by thoracic surgeon Sudish Murthy, MD, PhD. Following patient positioning in the left lateral decubitus position, four thoracoscopic ports were placed. The procedure began with subcarinal dissection and removal of level 7 lymph nodes to facilitate exposure. The azygous vein was dissected and divided, and the pleura overlying the esophagus was incised up to the thoracic inlet. To further facilitate airway exposure, the divided azygous vein was pexied to the parietal pleura, retracting the esophagus toward the spine and away from the airway in the process. This allowed for further dissection and mobilization of the trachea and the bilateral mainstem bronchi as far as the level of takeoff of the upper lobe bronchus.

Advertisement

With the necessary exposure achieved, the surgical team proceeded with bronchoplasty, beginning with the left main bronchus (Figure 3). A 16-mm polypropylene mesh strip was introduced with an overhang of approximately 2 to 3 mm on each side, given the 10-to 11-mm bronchial posterior membrane width. The team began by securing the lateral aspect of the mesh to the left main bronchus, starting distally and working toward the carina using interrupted 3-0 polyglactin. Importantly, each partial-thickness bronchial bite incorporated the posterior aspect of a cartilaginous ring.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b5e7ee9d-965e-4407-aff9-35683fb6df91/23-HVI-3914171-CQD-Inset3_jpg)

Figure 3. Robotically assisted tracheobronchoplasty, visualized from the right thoracic cavity, with the patient’s head toward the top of the figure. The right lung has been reflected anteriorly, allowing for exposure of the posterior bilateral main bronchi (outlined).

The procedure continued with plication of the membranous airway using simple interrupted 3-0 polyglactin. First the endotracheal tube balloon was deflated and the tube retracted. Bites were then taken through the mesh, followed by partial-thickness plicating membranous airway bites, followed by passage of the needle back through the mesh. Importantly, these plication sutures were not yet tied. A total of four plication sutures was required. The medial aspect of the mesh was secured to the medial left main bronchus cartilaginous rings in a similar fashion as before, but this time utilizing interrupted barbed PDS suture, rather than polyglactin, for an approximate bronchial width of 10 to 11 mm. Only after the mesh was secured both medially and laterally were the plication sutures tied down, in order to prevent tearing of the delicate membranous airway.

Advertisement

Attention was then turned to the trachea, beginning by securing the mesh to the superior left tracheal edge with partial-thickness cartilaginous bites, each incorporating a different tracheal ring. This was followed by plication of the membranous trachea, with two plication sutures per row. An additional two rows were placed, moving inferiorly toward the carina. The distal end of the mesh was secured to the carina.

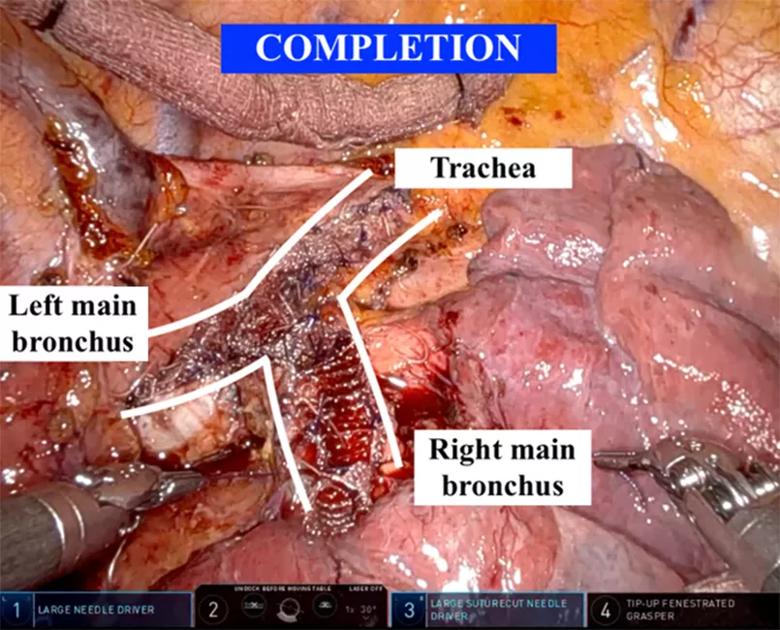

Lastly, the right main bronchus was performed in similar fashion to the left, with the same size mesh, to complete the operation (Figure 4). One must be cognizant of the shorter right mainstem bronchus and avoid narrowing the right upper lobe bronchus.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ba2cc54a-c218-4545-9686-dc3f0406dc21/23-HVI-3914171-CQD-Inset4_jpg)

Figure 4. Completion tracheobronchoplasty, with mesh approximated to the posterior membranous trachea and mainstem bronchi.

Bronchoscopy was performed upon completion to confirm patency of the lobar and segmental bronchi. An intercostal nerve block was performed, and the patient was extubated in the operating room.

Postoperatively, the patient recovered without complication and was discharged home on postoperative day 3. At six-month follow-up, his FEV1 and FVC were improved (65% and 98% predicted), and his six-minute walk test result was stable from the time of the tracheal stent. Subjectively, he noted an improvement in his dyspnea.

Conceptually, the operation is divided into two main parts. The first involves exposure of the posterior trachea and the bilateral mainstem bronchi out to the bronchus intermedius. The second consists of four main steps that are repeated for each segment of the airway: (1) securing the mesh along one edge of the cartilaginous trachea or bronchus, (2) placing sutures to plicate the membranous airway, (3) securing the free side of the mesh to its corresponding edge of the airway and (4) tying the plication sutures as the last step.

Advertisement

Minimally invasive robotically assisted tracheobronchoplasty is a recently developed technique currently performed at select centers nationwide, including Cleveland Clinic. Whereas previous techniques required a much larger thoracotomy incision, surgeons can now perform this procedure through small incisions that heal quickly and result in less postoperative pain.

Tracheobronchomalacia is currently a grossly underdiagnosed disease, but as improved diagnostics continue to emerge, this type of complex airway repair is expected to become far more common. Encouragingly, with its multidisciplinary team of expert thoracic surgeons and pulmonologists, Cleveland Clinic is poised to provide state-of-the-art personalized care for patients suffering from tracheobronchomalacia.

Dr. Barron is a general surgery resident and thoracic surgery research fellow, Dr. Raja is Surgical Director of the Center for Esophageal Disease, and Dr. Murthy is Section Head of Thoracic Surgery, all in the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery in Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute.

Advertisement

Target levels of oxygen saturation might only be achieved around one-third of the day, according to available literature

New developments offer providers more sophisticated options

Lessons learned from cohorting patients and standardizing care

Despite a decline in numbers, the demand for respiratory therapists continues to rise

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Milestone minimally invasive surgeries reduce pain and recovery time

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Quality improvement project addresses unplanned extubation