Document addresses screening and treatment while underscoring need for more randomized data

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) tackles an often undiagnosed but prevalent health problem — sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) — and underscores its connection with cardiac arrhythmogenesis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The document, published in Circulation, was drafted by a panel that includes Cleveland Clinic experts Reena Mehra, MD, MS, and Mina Chung, MD, as chair and vice chair, respectively.

“Strong evidence indicates that sleep-disordered breathing can lead to consequences such as autonomic nervous system fluctuations, recurrent hypoxia and alterations in carbon dioxide/acid-base status, which can directly affect cardiac function,” says Dr. Mehra, who is Director of Research in Cleveland Clinic’s Sleep Disorders Center and holds appointments in its Respiratory Institute and Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute. “Our panel’s data synthesis is designed to increase knowledge and awareness of the existing science in this area.”

“The association of sleep apnea and obesity with atrial fibrillation has made identification and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing and weight loss an important part of lifestyle and risk factor reduction in the treatment of atrial fibrillation,” adds Dr. Chung, a staff cardiologist in the Section of Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology. She also chaired the 2020 AHA scientific statement on lifestyle and risk factor modification for reduction of atrial fibrillation.

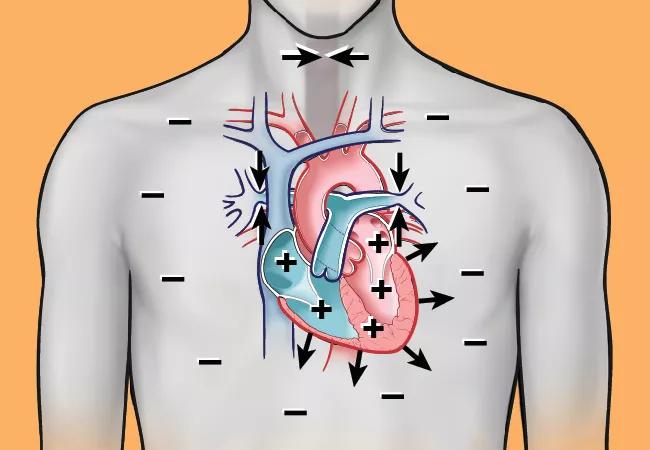

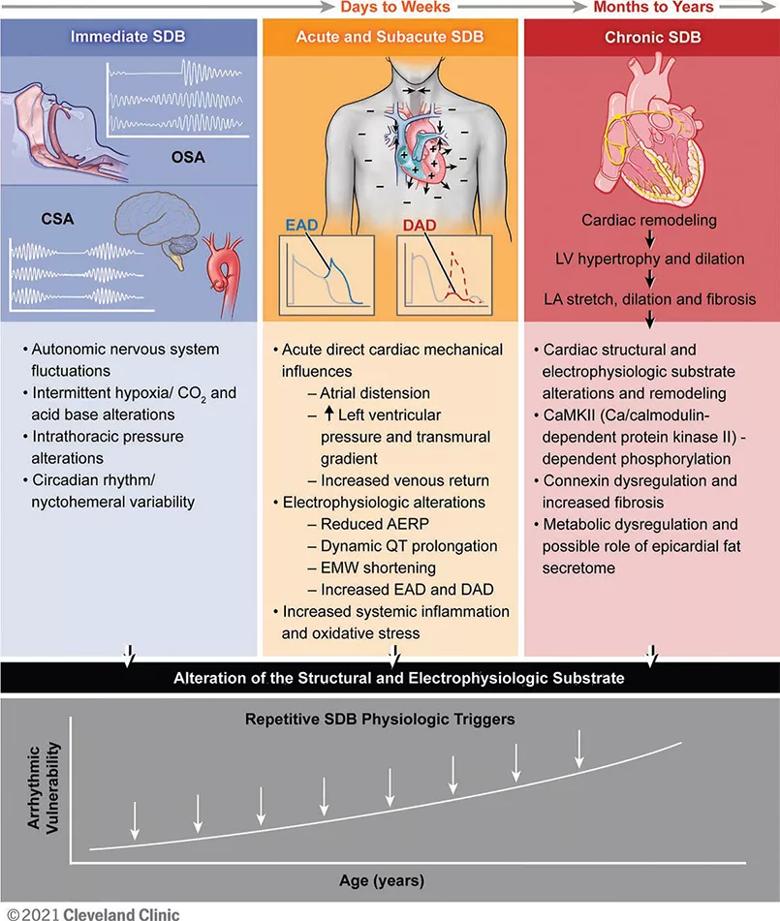

Nearly 1 billion individuals worldwide suffer from SDB, which is associated with excessive cardiopulmonary morbidity. Abundant evidence from mechanistic studies indicates that the physiological stress of SDB has sustained biological effects, which alter cardiovascular substrate and increase risk for cardiac arrhythmogenesis (Figure). In uncontrolled studies, treatment of SDB has been shown to reduce recurrence of arrhythmia after interventions such as catheter ablation and cardioversion for atrial fibrillation (AF).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/77263a7a-cbaf-48b0-9cc8-6cb814c848af/22-HVI-3042608-Inset_jpg)

Figure. Immediate, acute/subacute and chronic sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) pathophysiology contributing to cardiac arrhythmogenesis. SDB includes obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), characterized by upper airway collapse, and central sleep apnea (CSA) with abnormalities in hypoxic ventilator mechanisms (carotid chemoreceptors) and carbon dioxide chemosensitivity (medullary chemoreception). Over time, with increasing age, the SDB-induced pathophysiological effects on the cardiac substrate enhance arrhythmia vulnerability. EAD = early afterdepolarization; DAD = delayed afterdepolarization; AERP = atrial effective refractory period; EMW = electromechanical window; LV = left ventricular; LA = left atrial. Reprinted from Mehra et al., Circulation. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001082. Copyright © 2021 Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography.

The evidence for the scientific statement came from detailed literature searches in PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus conducted by the author panel. Selected publications consisted of English-language original articles, guideline statements and review articles.

The statement was peer reviewed by outside experts in epidemiology and clinical, translational and experimental research focused on SDB or cardiac arrhythmias. The panel’s findings are not formal clinical recommendations but rather considerations and suggestions for best clinical practice, based on at least 80% agreement among panel members.

The panel’s key conclusions include the following:

Advertisement

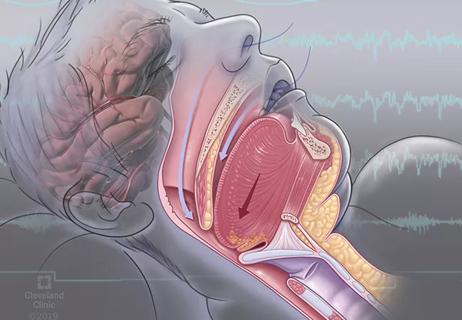

SDB subtypes relevant to the AHA document include obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), central sleep apnea (CSA), and CSA–Cheyne-Stokes breathing (CSB).

Regarding OSA, the panel notes that symptom-based screening questionnaires have limited predictive value in patients with AF because few of these individuals have daytime sleepiness. However, a validated OSA screening instrument in paroxysmal AF that combines neck circumference, age, body mass index and snoring holds promise. No reliable screening tools are available for CSA. The associations between cardiac dysfunction and CSA and CSB are likely to be bidirectional, the panel concludes.

Among existing guidelines underscored by the panel were recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) for prudent treatment of SDB in patients with AF and for including the presence of OSA in risk stratification, as well as recommendations from the ESC and the AHA for SDB screening in patients with documented or suspected bradycardia or conduction disorder.

“We were very careful to state that identification of SDB and diagnostic testing and treatment should be confined to patients for whom there is a high index of suspicion for sleep apnea,” Dr. Mehra says. “SDB should be a consideration in those who are deemed at risk who have atrial fibrillation or other cardiac arrhythmias, but current evidence does not support universal screening.”

While noting that many observational studies suggest that treatment of SDB improves AF outcomes, the panel identifies confirmation of this association in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as a research priority. “Currently there are only small or limited randomized studies that have addressed SDB and AF, and they have shown conflicting results,” Dr. Chung says.

Advertisement

“We definitely need adequately powered, rigorously designed RCTs to ascertain whether intervening in patients with SDB actually improves arrhythmia outcomes,” Dr. Mehra adds. “The bulk of the data we have are for AF, and research is needed on other arrhythmias and on the impact of other factors.”

Another panel priority is RCTs examining continuous positive airway pressure and newer therapies — such as neurostimulation, supplemental oxygen and medication — for treating SDB in people with arrhythmias, including ways to optimize treatment adherence.

“It appears that responses to different interventions vary among individuals,” Dr. Mehra observes. “Therefore, if diagnostic testing is consistent with OSA, a patient-provider discussion should then include an understanding of patient preferences. This includes exploring the range of therapeutic options available based on the severity and subtype of sleep-disordered breathing, such as lifestyle modification and interventions ranging from oral appliances to upper airway surgery or positive airway pressure.”

“My hope is that this AHA statement will increase global awareness of the high prevalence of SDB among patients with cardiovascular disease in general and rhythm disorders in particular,” says Michael Faulx, MD, a Cleveland Clinic cardiologist with a special interest in the cardiovascular effects of sleep apnea. “The recommended routine screening will undoubtedly allow more symptomatic SDB patients to benefit from diagnosis and treatment. I also believe the AHA statement will foster a greater national interest in organizing well-designed mechanistic trials that explore the benefit of diagnosing and treating SDB with the goal of improving cardiovascular outcomes.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

LAA closure may be compelling option in atrial fibrillation ablation patients at high risk of both stroke and bleeding

UK experts compare and contrast the latest recommendations

While results were negative for metformin, lifestyle counseling showed surprising promise

Investigational pulsed-field ablation system also yielded procedural efficiencies

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

ACC/AHA panel also upgrades catheter ablation recommendations

For the first time, risk is shown after accounting for underlying contributions of pulmonary disease

Retrospective analysis finds “hypoxic and sleepy” subtype to confer greatest risk