Tour-de-force reconstruction in a man with Marfan syndrome

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/488ab456-b0c2-4816-b302-07699779be85/16-HRT-2446-Elephant-Trunk-CQD-Hero_jpg)

Aortic Dissection: Multistage Repair Featuring a Branched Frozen Elephant Trunk Technique

By Eric E. Roselli, MD, and Brian Griffin, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 42-year-old man from North Carolina referred himself to the Aorta Center in Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart & Vascular Institute in 2015. At age 8, he had been diagnosed with Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder that led to an imbalance in the maintenance and turnover of his connective tissues.

In early adulthood, he developed an aneurysm of the root of his aorta. In 2001, at age 28, he suffered an acute type A aortic dissection, a tear in the intimal layer of his ascending aorta that led to complete separation of the layers of the aorta from the root to the bifurcations of both femoral arteries. He underwent an emergency operation to replace his aortic root and ascending aorta, including reimplantation of the coronary arteries and replacement of the aortic valve with a mechanical prosthesis (Bentall procedure with a composite valve graft). The operation was limited to addressing the most life-threatening segments of the aortic dissection even though the dissection had extended all the way down through the femoral arteries.

Several years later, when the patient was 35, his providers noted that the residually dissected and untreated segments of his aorta had begun to dilate, and regular imaging was performed to monitor the dilation.

Over the two years before he came to Cleveland Clinic, the patient’s aorta had grown to a size that prompted consideration of additional aortic replacement. But the surgical options recommended at outside institutions carried high risk for death, stroke and paralysis, so the patient put off further surgery until learning of the multidisciplinary expertise of Cleveland Clinic’s Aorta Center and Marfan Syndrome/Connective Tissue Disorders Clinic.

Advertisement

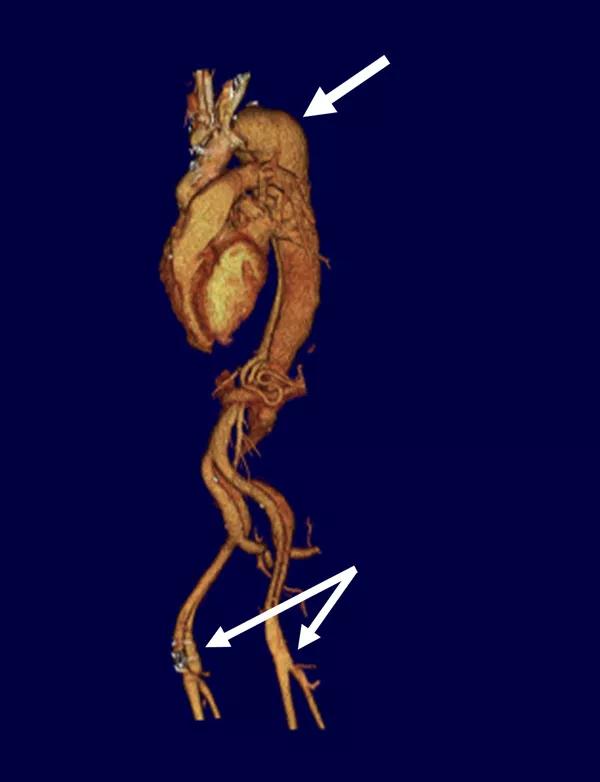

Upon the patient’s presentation at Cleveland Clinic, his CT scans were retrieved for review. Their raw data were downloaded to our servers, and reconstruction software was used to perform detailed image analysis. At presentation, his maximum aortic diameter was greater than 7 cm, and the aneurysmal degeneration extended from the end of his previous repair through the entirety of the aorta and into both femoral arteries, each of which measured nearly 3 cm (Figure 1).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0e70c75e-0c35-4738-ab27-8d7877741c91/16-HRT-2446-Elephant-Trunk-CQD-Fig1_jpg)

Figure 1. Volume-rendered three-dimensional CT reconstruction of the contrast-enhanced images from outside institutions, reformatted at the Aorta Center. The top arrow denotes the maximally dilated segment of the chronically dissected aorta in the distal aortic arch. The bottom arrows indicate the aneurysmal femoral arteries on both sides.

With these image analyses as our basis, our team developed a comprehensive staged treatment plan to include multiple operations over a two-week period. The plan was fleshed out with a series of additional evaluations, as follows:

Advertisement

After discussion with the team, mitral repair was added to the plan for the first-stage operation. The patient was admitted for warfarin reversal with heparin bridging, and coronary catheterization via a right radial approach demonstrated preserved coronary anatomy without occlusion or aneurysm. This approach allowed for more direct access to the coronaries and avoided both the aneurysmal femoral arteries and navigation through the dissected distal aorta.

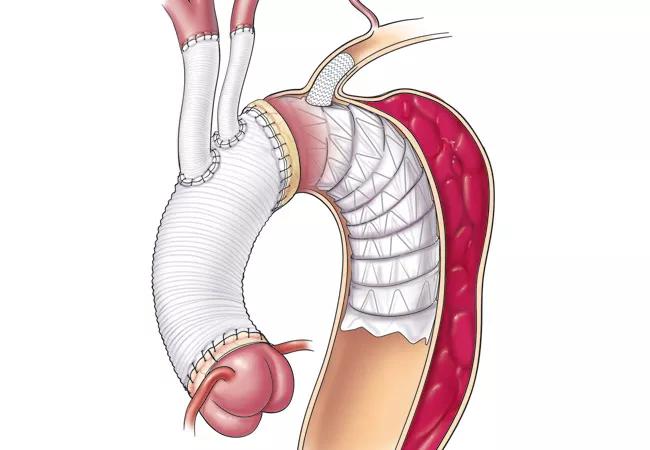

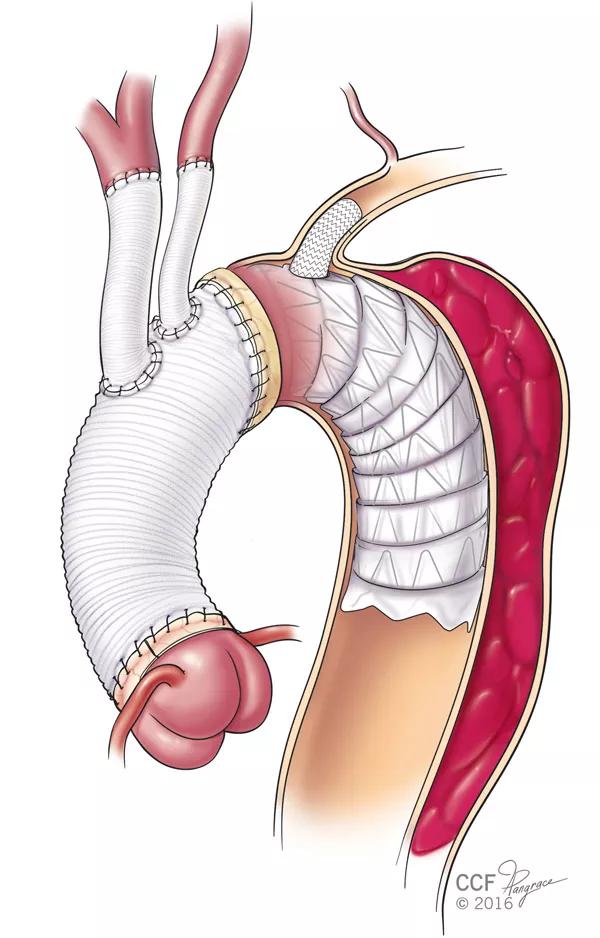

The first operation was a redo sternotomy with right axillary artery cannulation to provide the safety of selective antegrade brain perfusion. The mitral valve was repaired, and the aortic arch was replaced using a branched modified frozen elephant trunk technique developed by one of the authors (Dr. Roselli) that includes the following (Figure 2):

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c5d8a3c3-5632-4bf1-b5cd-684fced0a98b/16-HRT-2446-Elephant-Trunk-CQD-Fig2_jpg)

Figure 2. Illustration demonstrating the branched frozen elephant trunk procedure.

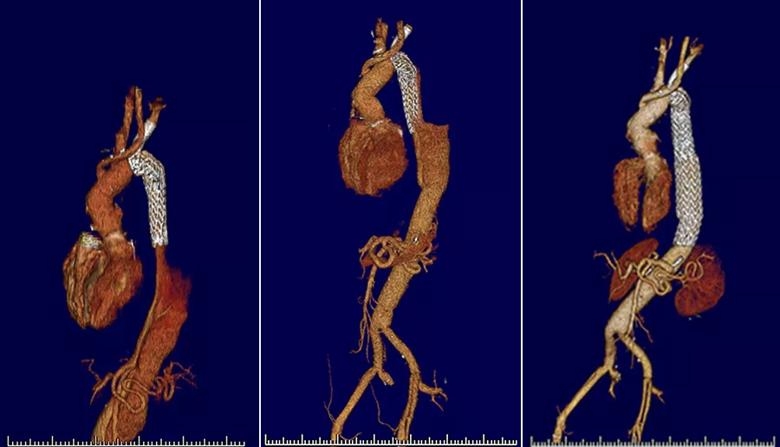

After a week and a half of recovery, the patient underwent the second-stage operation: open thoracoabdominal repair, including repair of both femoral artery aneurysms, separate branch grafting to each of the visceral and renal arteries, and preservation of the internal iliac arteries, which are known to be important for spinal cord protection. The repair was limited to a level just above the diaphragm to maintain important intercostal branches and provide a period of ischemic conditioning to the spinal cord before the third-stage operation, which consisted of finalizing treatment with complete replacement of his aorta from the left ventricle to the superficial femoral arteries (Figure 3).

Advertisement

Three days after the open thoracoabdominal repair, he underwent completion with a thoracic endovascular aortic repair with access through the recent femoral artery interposition graft.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/17099e6f-f306-48aa-9b6e-039b5c32072d/16-hrt-2446-combined-b_jpg)

Figure 3. Volume-rendered three-dimensional CT reconstructions demonstrating the aorta after the first but before the second stage of the aortic repair (left), the period between the second and third stages (middle) and follow-up at three months after repair completion (right).

The patient recovered well from this tour de force reconstruction and returned home to North Carolina by car with no serious complications and fully neurologically intact. He has since returned for three-month follow-up and will continue to undergo annual imaging to monitor his repairs and native vasculature.

Dr. Roselli is a cardiothoracic surgeon and Director of the Aorta Center.

Dr. Griffin is Head of the Section of Cardiovascular Imaging and a staff cardiologist in the Marfan Syndrome/Connective Tissue Disorders Clinic.

Advertisement

Advertisement

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon