Lessons from a rapid response to a large pericardial effusion

By Faisal Bakaeen, MD, and Paul Cremer, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Mr. F is an 81-year-old African American man with a history of prosthetic knee joint infection with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. He had been in and out of the operating room (OR) over the past year to try to address it, without success. He ultimately underwent prosthesis explant and was given an antibiotic-loaded spacer. Three months later, he is scheduled for surgery to remove the spacer with possible revision total knee arthroplasty to follow.

Mr. F has had poorly controlled hypertension for 40 years despite attempted treatments with every class of antihypertensive medication. He has left ventricular hypertrophy, an ejection fraction of 50 percent, chronic atrial fibrillation, a VVIR pacemaker, chronic kidney disease and anemia.

On the day of surgery, intravenous line placement proved difficult. An awake double-lumen left internal jugular central venous pressure line was placed. Mean systolic pressures of 150 mm Hg were recorded during the procedure.

At the time of induction, his pressures rose and fell, stabilized for more than an hour, then dropped precipitously. Pacemaker function remained unchanged. Central venous pressure was not recorded.

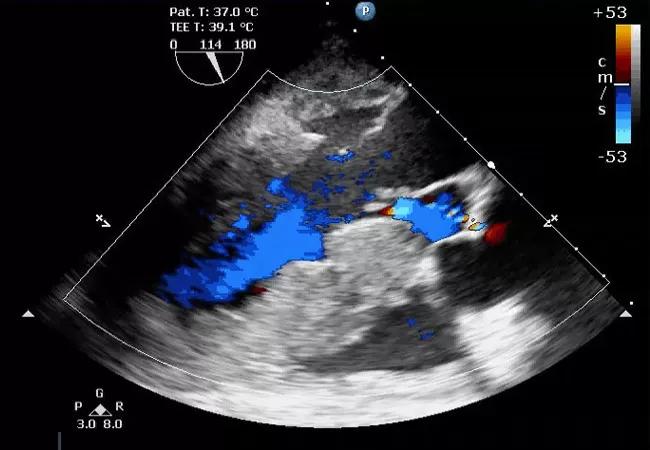

He was given epinephrine, and a norepinephrine infusion was started at 20 micrograms per minute. A transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe was placed and revealed a large pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e0016f0d-dcf6-4210-9835-ed1e500b89b8/17-HRT-3792-Big-Rescues-CQD-F1_jpg)

Figure 1. TEE findings showing a large pericardial effusion.

Emergent cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery consultation was called. Initially, aortic dissection was considered, but no dissection flap was seen on TEE. Consideration was also given to iatrogenic vascular injury, such as from central line placement, but etiology remained unclear.

Advertisement

His family asked that everything possible be done to save him.

The cardiac OR was notified for patient transfer, but with an open knee, it was deemed logistically impossible. In the meantime, pericardiocentesis was attempted unsuccessfully, then a subxiphoid pericardial window was performed, which resulted in the removal of about 500 mL of bright red blood.

Bleeding appeared to stop, blood pressure stabilized and vasoperessors were stopped. A pericardial drainage chest tube was left in place. The knee was quickly closed with the spacer left in, and Mr. F was sent to the critical care unit (CCU) for close observation.

Shortly after his arrival in the CCU, there was brisk drainage of bright red blood from the pericardial tube and the patient became hypotensive. He was stabilized with volume infusion and transfusions. The decision was made to take him to the OR for emergency exploration and control of bleeding.

On the way to the cardiac OR, Mr. F went into cardiac arrest, and CPR was initiated in the elevator. He was rushed to the cardiac OR.

A rapid infuser was set up by perfusion staff to quickly address hypovolemia, allowing infusion of a liter of fluid per minute. Unfortunately, even with this massive infusion, the patient was losing blood faster than it could be delivered.

An echocardiogram was done, and no volume was evident in the heart.

Simultaneously, an emergency sternotomy was performed and the pericardium was opened. Inside was a large amount of clot and red blood. Clearing out of this clot material revealed a dilated, discolored, bruised-looking aorta and innominate and pulmonary arteries. No active bleeding was evident.

Advertisement

Further exploration led to discovery of a contained posterior rupture of the aorta. The aorta was quickly cannulated and clamped above the site of the free rupture. The patient was placed on cardiopulmonary bypass, and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was induced. The clamps were removed to allow examination of the posterior tear, which extended from the sinotubular junction up into the proximal aortic arch on the lesser curvature.

The tear was fully excised and the aorta replaced using a hemiarch technique. The patient was rewarmed and successfully weaned off cardiopulmonary bypass. Temporary closure of the chest with a vacuum dressing was used because of ongoing coagulopathy.

Mr. F woke up with intact neurologic status, and definitive closure of the sternum was done the next day. He was discharged to a skilled nursing facility two weeks later. At 30-day follow-up, he was eating on his own and doing well. He subsequently underwent knee replacement and now has a functioning right knee prosthesis and is receiving physical therapy to enable him to walk independently in the near future.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5f482509-3cc1-42bd-ba6d-2942736a559a/17-HRT-3792-Big-Rescues-CQD-F2_jpg)

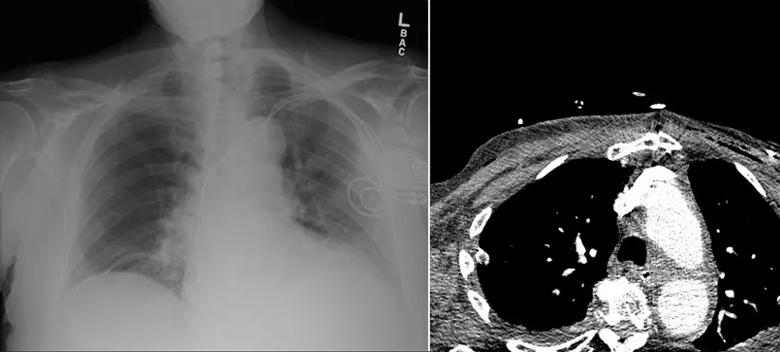

Figure 2. Although a preoperative chest radiograph (left) showed no evidence of an enlarged mediastinal or cardiac shadow to suggest an aortic aneurysm or a pericardial effusion, a postoperative CT (right) showed a generous aorta, suggesting that the patient was predisposed to aortic dissection or rupture.

This case brings up several questions:

Advertisement

Dr. Bakaeen (bakaeef@ccf.org) is a surgeon in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more