Atypical cells discovered after primary sclerosing cholangitis diagnosis

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/27d3a5f4-ca40-4de8-bc30-c3840cd5e1a2/22-CNR-3341124-CQD-Hero-Whipple_jpg)

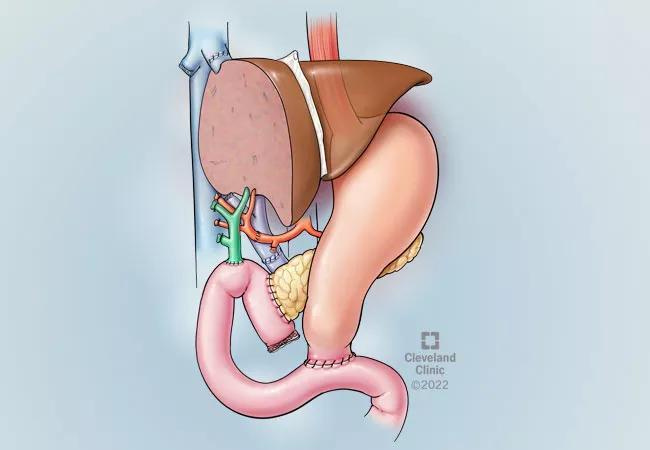

whipple procedure

Three years after undergoing a total colectomy, a 58-year-old patient with a history of ulcerative colitis presented with elevated alkaline phosphate numbers during routine lab work. This led to a significant workup, including several endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures (ERCPs) as well as cross-section imaging to evaluate the bile duct.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The ERCPs revealed the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), which can cause scarring of the bile ducts as well as severe liver damage. The medical team also performed brushings of the liver, which revealed that some cells in the intrahepatic bile ducts and distal bile ducts were suspicious for malignancy or the potential to turn malignant.

Due to organ dysfunction from progression of PSC, the patient needed a liver transplant. However, the transplant itself was not going to eradicate the concern about malignancy since the abnormal cells that were discovered were in the ducts outside of the liver. Due to these issues, the medical team determined that in addition to the liver transplant a whipple procedure would be required to remove the remainder of the bile duct. This would also include removing part of the pancreas, the duodenum and the gall bladder. Since the bile duct runs through the head of the pancreas, a whipple procedure was required to get it out in its entirety.

Taking care of patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis requires a specialized team. A medical oncologist, hepatologist, gastroenterologist as well as innumerable nurses and advanced practice practitioners, nutritionists and several residents helped take care of the patient leading up to surgery and afterwards. All members of the medical team were deeply involved in frequent discussions throughout the patient’s care. A great deal of multidisciplinary discussion and planning occurred to determine the timing and logistics of the liver transplant and the whipple procedure.

Advertisement

Leading up to the liver transplant, the medical team formulated several contingency plans to ensure the procedures went smoothly. They decided ahead of time that since both operations are big stressors on the body, it would be ideal to avoid doing both at the same time. Therefore, it was determined that the bile duct margin would be evaluated in the operating room by the pathologist and that if cancer was detected at that time, then they would proceed with a whipple immediately. Fortunately, the margins were negative for cancer, so the procedure was able to be delayed for three months to allow the patient’s body time to recover and prepare for the second operation.

“We wanted to do all we could to minimize risk factors and set the patient up for success in the operating room,” said Robert Simon, MD, a general surgeon specializing in hepatopancreaticobiliary surgery with Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Simon was the surgeon scheduled to perform the whipple portion, and he scrubbed into the liver transplant to help plan ahead. For example, understanding details such as the limb length of the bowel made it possible for the [whipple] procedure to be performed without having to take down the bile duct anastomosis. Conversely, Dr. Koji Hashimoto, the liver transplant surgeon, came in to assist during the whipple procedure to identify and protect structures that were unique to the liver transplant.

The patient has fully recovered from the liver transplant, and is making a swift recovery from the whipple procedure. Since the pathology of the bile ducts revealed microscopic forms of cancer, the medical team again discussed the risks and benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy and ultimately decided that the patient was cured since the entire bile duct was removed and there was no disease left behind. She will be followed closely with imaging and labs.

Advertisement

Whipples in liver transplant patients are rare, but usually they are performed years afterwards for unrelated issues. In this case, a whipple was indicated from the start, and was approached in a staged manner. “These cases are extremely rare but when they do occur, having a multidisciplinary team is needed, who knows how to work up PSC by getting brushings of the entire bile duct, identifying dominant strictures and recognizing at risk features,” says Dr. Simon. “It’s important to have subspecialty surgeons on hand to treat when needed, but most importantly, a team that communicates effectively, efficiently and often.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Minimally invasive approach, peri- and postoperative protocols reduce risk and recovery time for these rare, magnanimous two-time donors

Patient receives liver transplant and a new lease on life

New research shows dramatic reduction in waitlist times with new technology

Cleveland Clinic study shows positive outcomes for donors and recipients

Program's approach maximizes donor safety without compromising recipients' outcomes

Program expands as data continues to show improved outcomes

Research examines risk factors for mortality