When specialized surgery makes sense for moyamoya syndrome

Several weeks after giving birth via cesarean section, a 37-year-old woman began experiencing left-sided weakness and tingling, sensory changes and speech problems. The episodes, which occurred frequently and without warning, typically lasted only 30 seconds.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Over several months, as her symptoms worsened and the episodes lengthened, she sought care from multiple clinicians in her local community. Her first workup, for migraine, found no physiologic cause for her symptoms, which were attributed by a community neurologist to functional neuropathy or psychiatric issues.

New symptoms — brain fog and left-sided paralysis — and episodes that now lasted 1 to 2 minutes brought the patient to her local emergency department. When an electromyogram was negative, her symptoms were ascribed to stress.

Three days later, the patient again experienced an episode of transient left-sided paralysis and inability to speak. She contacted her primary care physician, who referred her to a second neurologist. Emergency MRI revealed a blockage in the right middle cerebral artery. The blockage was causing her to have 10 to 15 transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) daily, which had culminated in a stroke on the right side of the brain.

The presumed diagnosis was moyamoya syndrome; no interventional care was planned. The patient sought a second opinion from Cleveland Clinic. She was seen by Andrew Russman, DO, Medical Director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center and Head of the Stroke Program, and Mark Bain, MD, a vascular neurosurgeon and Head of the Endovascular Surgical Neuroradiology Section in the Cerebrovascular Center.

Moyamoya disease and moyamoya syndrome are similar but distinct entities. In both moyamoya syndrome and disease, as the narrowing of the large intracranial arteries progresses, secondary small vessel collaterals develop. On angiography, the collaterals appear similar to a puff of smoke on angiography, hence the term moyamoya, which is Japanese for “smoke in the air.”

Advertisement

“Moyamoya syndrome is a rare vasculopathy typically seen in adults,” says Dr. Russman. “It is usually caused by conditions such as sickle cell disease, neurofibromatosis, thyroid disease or accelerated atherosclerosis, and it can lead to ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage.” The first sign of moyamoya syndrome, as in this case, is often TIA or stroke. Other symptoms in adults include brain hemorrhage, headache, involuntary movements, seizures, and motor, sensory, gait, language or cognitive problems.

In contrast, moyamoya disease, which typically presents in children or young adults, involves progressive narrowing of the arteries that is idiopathic or due to a genetic susceptibility.

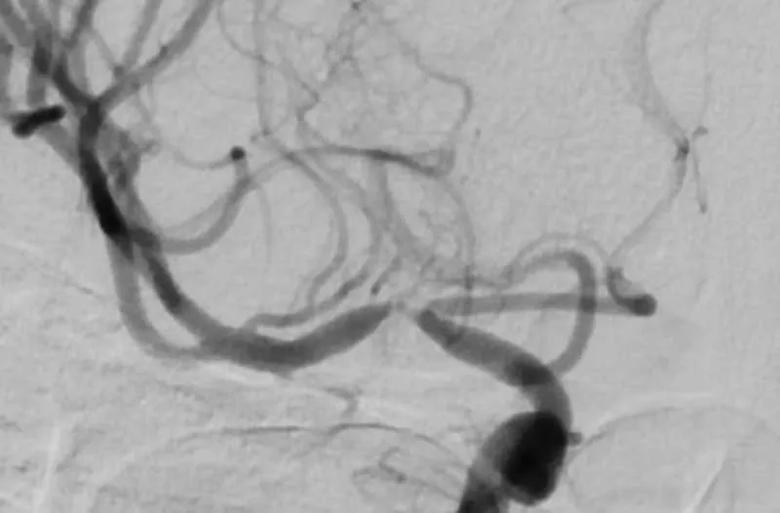

“A small percentage of patients with moyamoya syndrome present with brain bleeding when the blocked vessels rupture,” Dr. Russman notes. “In our patient, angiography and MRI perfusion with acetazolamide challenge showed that she had functional occlusion of her right middle cerebral artery and moyamoya-like changes (Figure 1). The left side of her brain was normal, so the condition was unilateral.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/917054f1-630a-4bec-949a-a5a625e66a52/22-NEU-3038364-CQD-Inset1-800x526-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Angiogram showing carotid and middle cerebral artery stenosis resulting from the patient’s moyamoya syndrome.

Results of the specialized imaging and the patient’s history and symptoms were discussed by experts at one of the Comprehensive Stroke Center’s semiweekly multidisciplinary moyamoya boards. Given the history of repeated TIAs and evidence of failure of the cerebrovascular reserve on the acetazolamide challenge, the team decided to recommend surgery.

Advertisement

“Not every patient with moyamoya syndrome is a candidate for surgery,” Dr. Russman says. “In some cases, blood flow is being automatically rerouted in a natural way and surgical bypass is not needed.”

“It’s also necessary to screen patients to ensure they have a favorable donor vessel for surgical bypass,” adds Dr. Bain.

Medical management with antithrombotic therapy may be prescribed if a patient has preserved cerebral blood flow and is asymptomatic. Surgery usually is indicated to avoid future complications and morbidity in patients with moyamoya syndrome who are symptomatic or who are asymptomatic and have severely impaired resting blood flow or inadequate perfusion.

“We have good evidence to suggest that patients with moyamoya disease or syndrome have fewer strokes and less risk of bleeding into the brain if they undergo brain bypass surgery than if they are managed medically,” notes Dr. Bain.

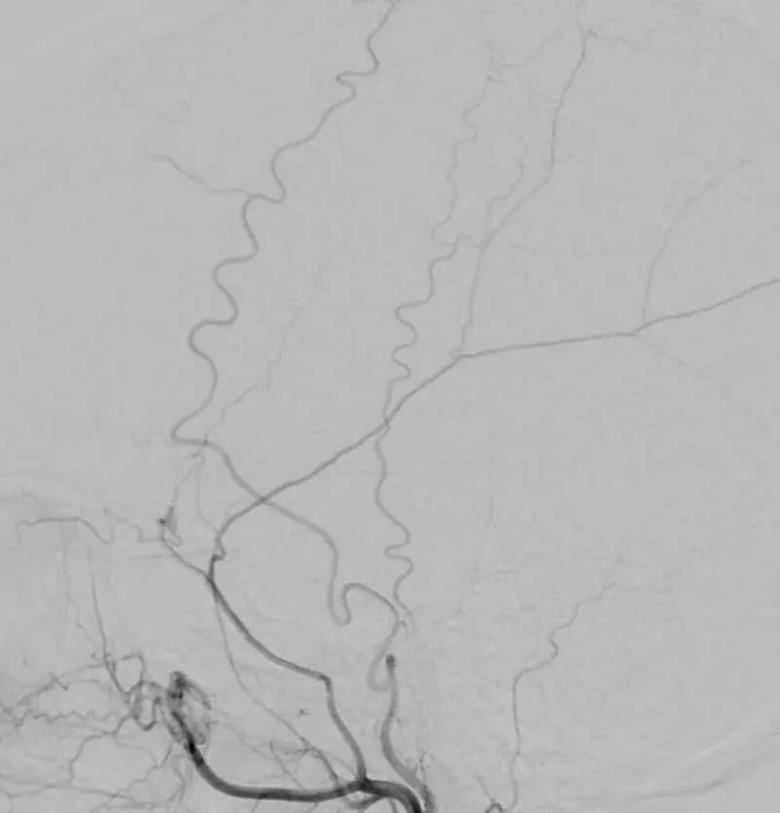

At Cleveland Clinic, both direct and indirect revascularization surgeries are performed for moyamoya syndrome. In the case of the 37-year-old postpartum patient, the direct technique was used. A team led by Dr. Bain directly connected the patient’s superficial temporal artery from her external carotid artery (Figure 2) to the cortical artery within the ischemic right hemisphere.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0a06262e-13ea-499f-a64e-c624554e6a18/22-NEU-3038364-CQD-Inset2-800x834-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Angiogram showing the external carotid artery used for surgical bypass.

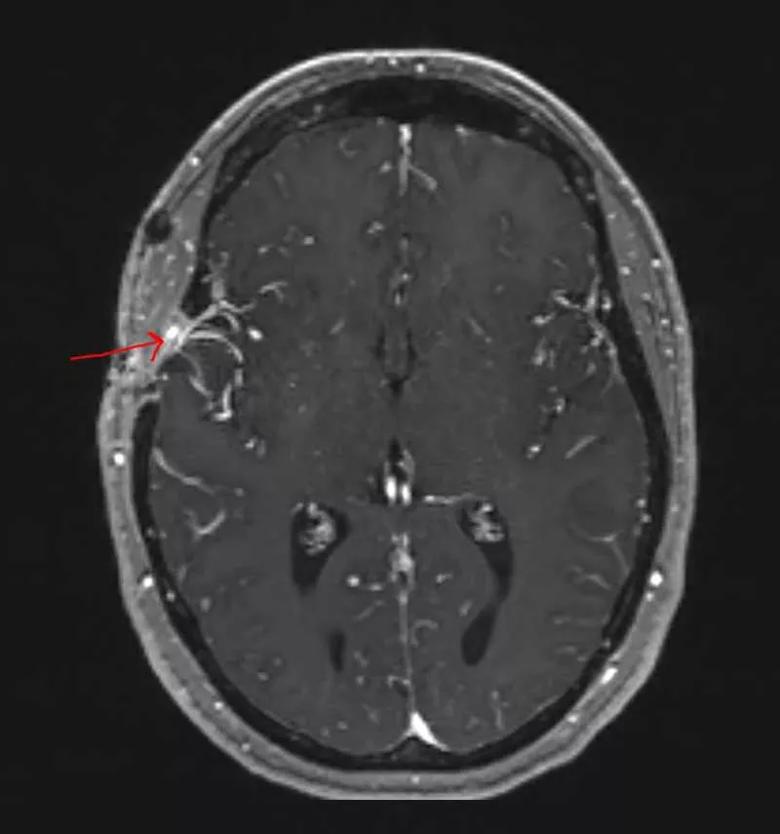

“We isolated the artery in the skin and sewed it to the artery in the brain to bypass the blocked internal carotid, bringing more blood flow to the brain and reducing the patient’s risk of stroke,” Dr. Bain explains (Figure 3).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/23bdd533-eb02-4a59-957d-5f7e972a1fca/22-NEU-3038364-CQD-Inset3-800x855-1_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative MRI of the patient with red arrow pointing to the bypass. Note the increased vascularity on that side of the brain.

Both before and after the procedure, the patient received care from neurocritical care physicians and advanced practice providers who specialize in treating individuals with moyamoya syndrome. She recovered without complications and has remained symptom-free through more than seven months of follow-up.

“Our patient was young and otherwise healthy, which contributed to her transient symptoms despite the small strokes she suffered and also helped make her recovery uneventful,” Dr. Bain concludes. “The key in this case was a good workup and blood vessel imaging. Because moyamoya syndrome is rare, it’s not something typically seen in community practice. Referral to a specialized center can ensure that these patients get the right treatment.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A passionate specialist surveys the field’s past, present and future

Evolving thinking on when and how to treat brain aneurysms and AVMs

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature